Prehistoric Tattoos Were Made with Volcanic Glass Tools

Volcanic glass tools that are at least 3,000 years old were used for tattooing in the South Pacific in ancient times, a new study finds.

The skin-piercing tools could yield insight into ancient tattooing practices in the absence of tattooed human remains, the researchers said.

Research conducted over the past 25 years found 5,000-year-old tattoos on a mummy in the Alps. However, such exceptionally preserved human remains are rare, which makes it difficult to use them to learn more about the ancient history of tattooing. [8 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

One potential way to learn more about prehistoric tattooing is to unearth the tools used to make the markings. However, until now, archaeologists had discovered few ancient tattooing implements, likely because perishable materials were often used to make them, said study co-author Robin Torrence, an archaeologist at the Australian Museum in Sydney.

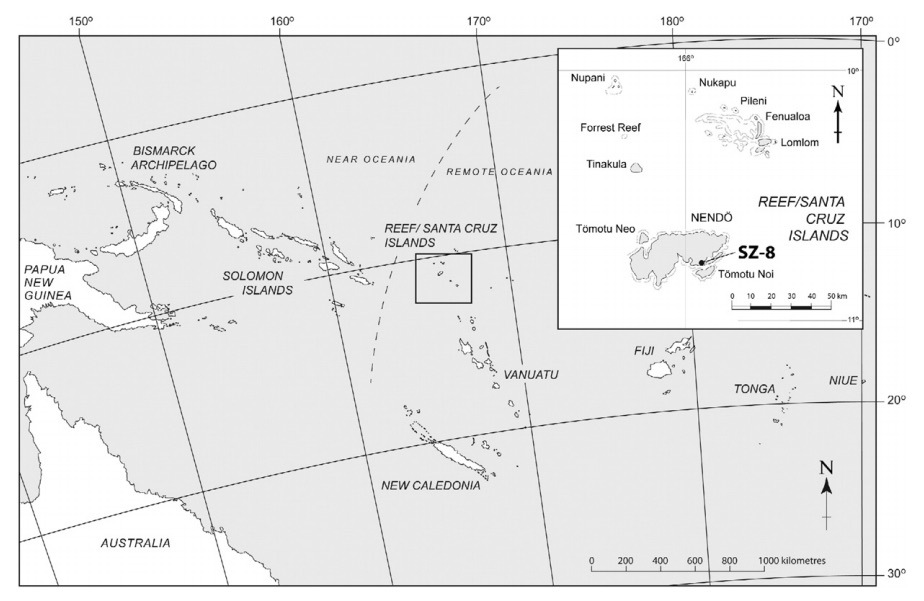

Torrence and her colleagues focused on prehistoric tattooing in the Pacific, in hopes of learning more about the practice in relation to wider social changes in the region. "Tattooing is a very important cultural practice in the Pacific even today," Torrence told Live Science. "In fact, the English word 'tattoo' comes from a Pacific Polynesian word: tatau."

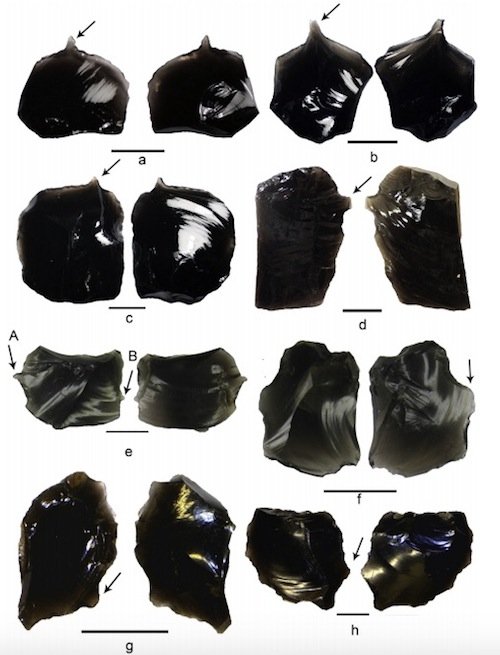

The scientists analyzed 15 obsidian artifacts recovered from the Nanggu site in the Solomon Islands. (Obsidian is a dark natural glass that forms when lava cools.) The creators of these artifacts, which are at least 3,000 years old, reshaped naturally occurring obsidian flakes so that each possessed a short, sharp point on its edge, the researchers said.

To create a tattoo, the surface of the skin must be broken so that pigment can be embedded and thus remain under the skin permanently after the wound heals. In 2015, the researchers performed 26 tattooing experiments with pigskin, using black charcoal pigment and red ochre dye, over the course of about four months. They used obsidian tools that copied the size and shape of the ancient artifacts from Nanggu.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When the scientists compared the ancient Nanggu artifacts with those used in the experiments, they found that both sets of tools had similar signs of wear and tear, such as microscopic chipping, rounding and blunting of the edges, and thin scratches. They also detected residues of blood, charcoal and ochre on the Nanggu artifacts.

"The research demonstrates the antiquity and significance of human body decoration by tattooing as a cultural tradition amongst the earliest settlers of Oceania," Torrence said.

Initially, the researchers thought these ancient Solomon Islanders might have used these tools as awls to make cloth and other items from animal skin and hide.

"However, this possible explanation faced the problem that there were extremely limited species of appropriately large animals in the tropical ecological zone that were hunted for the use of their skins," Torrence said. Previous research found that "possum and lizard skins have been used as the membrane of drums, but the skins require very little preparation beyond cutting off the tail and head of the animal," she said.

These findings may help researchers identify and learn more about how ancient obsidian tools elsewhere in the world might have also been used — "for example, in Mesoamerica, where obsidian was used in blood-letting rituals, or perhaps in other places where the practice of tattooing cannot be detected by any other means," Torrence said.

Torrence and her colleagues Nina Kononenko, of the Australian Museum, and Peter Sheppard, of the University of Auckland in New Zealand, detailed their findings in the August issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

Original article on Live Science.