Q&A with a Dinosaur Hunter: How Jack Horner Changed Paleontology

Paleontologist Jack Horner found his first dinosaur at age 8, and he hasn't stopped "digging" since. Despite his dyslexia and never having graduated from college, Horner changed the way researchers study dinosaurs, and is now a professor of paleontology at Montana State University and a curator of paleontology at the Museum of the Rockies.

Live Science caught up with Horner at the "Dino Dig," an exhibit at Liberty Science Center in New Jersey that encourages kids to hunt for replicas of dinosaur bones buried in about 35 tons (32 metric tons) of sand. The science center also honored Horner at its fifth annual Genius Gala on Friday (May 20).

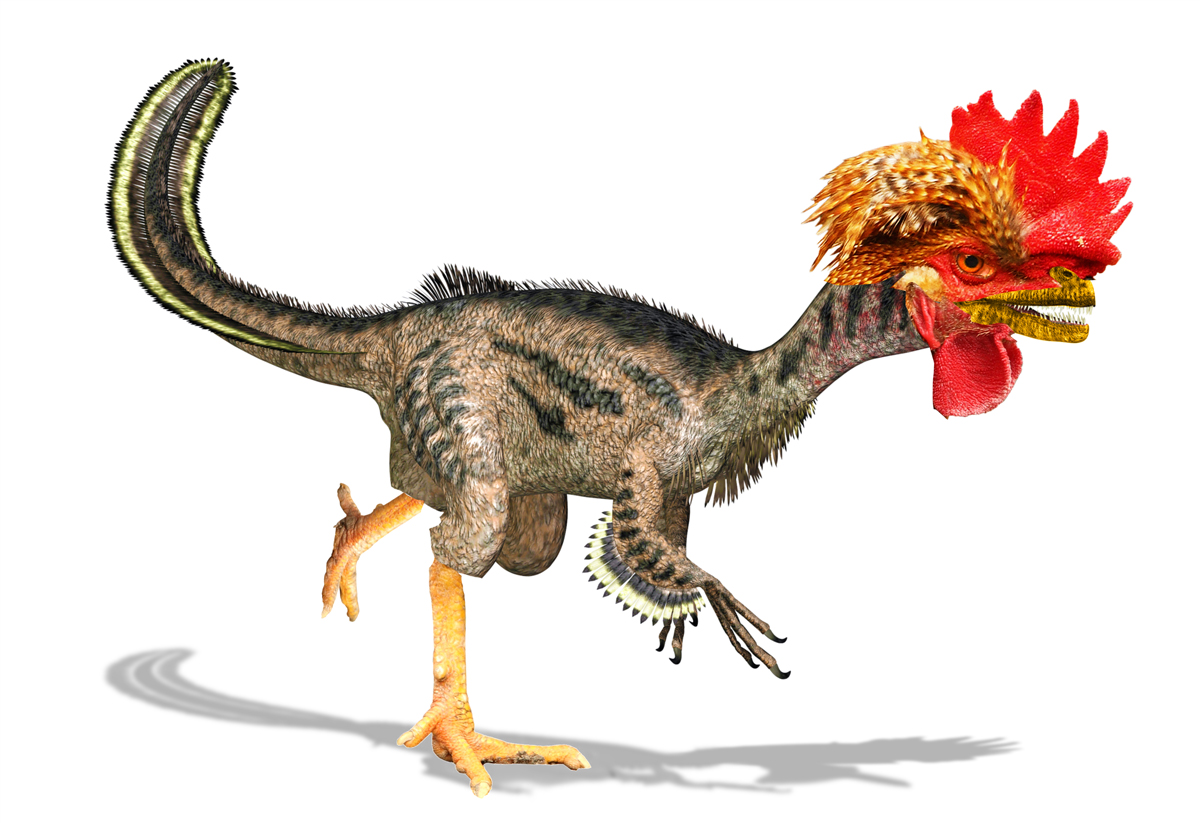

School-age children, who know him from his work advising the "Jurassic Park" movies, scrambled to get his autograph. Afterward, Horner talked with Live Science about growing up with dyslexia, how he found evidence suggesting that dinosaurs were social animals and how he's trying to reverse-engineer a chicken into a dinosaur, although he's hung up on just one part. [Infographic: How to Make a Dino-Chicken]

Growing up with dyslexia

Live Science: When did you start getting interested in dinosaurs?

Jack Horner: I've been interested in paleontology my whole life. I found my first dinosaur bone when I was 8, and I found my first dinosaur skeleton when I was 13.

Live Science: How did you find a dinosaur bone when you were 8 years old?

Horner: My father had remembered seeing some big bones when he was young out on a ranch that he owned in Montana. He took me out there when I was interested, and I wandered around until I found one.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Live Science: I heard that you have dyslexia. How did that affect you growing up?

Horner: Growing up was just terrible, because everybody thinks you're stupid and lazy. It's funny that they didn't understand that a long time ago. And they still don't. There's still a disconnect between kids who have learning problems and people understanding them.

One of the things that I'll be working on is with the chancellor at Chapman University, in Orange, California. We're going to see if we can figure out ways to better integrate kids with dyslexia schools into universities.

Live Science: I heard you flunked out of college seven times. But you kept going back?

Horner: I wanted to be a paleontologist, and there were lots of courses in paleontology at the University of Montana, where I was going to school. And so I just kept on taking them. But I read at a low third-grade level, so there wasn't any possible way that I could pass the test.

Live Science: That sounds really difficult.

Horner: Yeah, it's just impossible. A person with dyslexia is good at spatial things and putting big ideas together and making new ideas. But we're not very good at anything that schools have designed to test people.

I went to college for seven years and I flunked out seven times. When I thought I was finished, I started applying for jobs. I basically looked at all of the English-speaking museums in the country and other parts of the world. I got three job offers, and I took a museum technician job at Princeton University just because it was the smallest town. [7 Science Museums to Visit This Summer]

Live Science: So you didn't get a degree?

Horner: No, I do not have a degree of any kind. I got two honorary doctorates, but I do not have a normal degree — not a bachelor's, a master's or a Ph.D.

I went to Princeton as a preparator [a person who prepares, installs and maintains museum exhibits] in 1975 and discovered the baby dinosaurs in Montana in 1978. So, three years later, I published my first paper in the journal Nature. [Image Gallery: Dinosaur Daycare]

Live Science: Was it challenging to write a research paper with dyslexia?

Horner: I had written a lot of papers while I was in school, and I did really poorly. But one of my teachers told me, "As long as the science was good, somebody would always help me with it." I found that was true. When I submitted my paper to Nature, it was not very pretty, but on the other hand, the science was really good.

The editors there helped me out, and I had some people at Princeton who helped as well, before I even got it submitted.

When I published that paper, Princeton promoted me to research scientist. I couldn't have students, but I was able to write grants, and so I wrote a couple of NSF [National Science Foundation] grants that I got. A couple of years later, Montana State University was looking for a curator, and since I was at that level, I got that job in 1982.

But since I didn't have a Ph.D., they wouldn't let me have students, they wouldn't let me teach classes. But four years later, they did.

Live Science: Why did they change their minds?

Horner: I got a MacArthur Fellowship. After that they let me be a professor and teach classes and have graduate students, including Ph.D. students.

Game-changing findings

Live Science: You famously found evidence in 1978 that dinosaurs were social animals that cared for their young. What was the evidence?

Horner: That was the first discovery. They were 15 baby dinosaurs in a nest and they were twice as big as they would have been when they hatched. So, they stayed in their nests while they at least doubled in size.

We find nesting grounds all over the world now, and the nests are close together, so it suggests they were colonial nesters.

We also find lots of evidence that they traveled in herds, because we find these massive, monolithic dung beds.

[Horner has also found that baby dinosaurs look different from adult dinosaurs, a view contrary to that held by some other scientists who say that these specimens are a different species altogether. For instance, there is debate over whether Nanotyrannus is a unique species or simply a young Tyrannosaurus rex.] [In Photos: Montana's Dueling Dinosaur Fossils]

Live Science: You're also pretty hands-on with fossils, cutting them apart sometimes. Was that a new technique at the time?

Horner: People have been looking at the internal structure of dinosaurs for a long time. But basically they would ask a museum for extra dinosaur parts, like broken pieces. And so, they weren't getting very good samples.

I realized that most of the information about the growth of the dinosaurs was on the insides of their bones. Starting in the 1980s, we began to disassemble the bones, and take a mold and cast of them. Then you still have the original morphology — you can still study the body.

But then you can take the piece you took out and cut it, slice it up, and you have the entire circumference [to look at the dinosaur's growth rings, which look like a tree's rings]. That's how we now determine the age of dinosaurs, their rate of growth and their physiology.

We started doing that with leg bones, and now we can do it with skulls. For a long time, people thought it was destructive paleontology. But it's not destructive if you mold it, and cast it, and put a cast back in so that the morphology is still there.

Dino-chicken dreams

Live Science: You're also working on the so-called "chickenosaurus." Can you tell us about that?

Horner: We've got a project to retro-engineer a bird. We're looking at giving a bird a long bony tail, arms and hands instead of wings, a dinosaur-like head rather than having a beak like a bird, and basically changing the way it walks.

I think we have all of the parts, we can do all of these things so far, except we don't have a long bony tail.

Live Science: The tail is the hardest part?

Horner: We thought it would be relatively easy, and it turned out to be a lot harder than we expected. We've got three laboratories working on it.

Jurassic Park

Live Science: How did you go from professor to becoming an adviser for the "Jurassic Park" franchise?

Horner: I had written a book called "Digging Dinosaurs" [Workman Pub Co., 1988], and in that I talked about dinosaur social behaviors. Michael Crichton read my book and then he created his "Jurassic Park" character based on my character. His Dr. Alan Grant is supposed to be a paleontologist who works on dinosaur behavior in Montana.

When Steven Spielberg made the movie, he called and asked me if I would be the adviser, and make sure that Sam Neill could portray my character. [Paleo-Art: Dinosaurs Come to Life in Stunning Illustrations]

Live Science: What kind of advice did you give?

Horner: I worked with Steven directly — basically, I was his assistant. I sat next to him and answered questions for him. My job was to make sure the dinosaurs were as accurate-looking as they could be, and to make sure that the movie stars pronounced their words correctly. Also, to make sure that the science was as good as we could make it.

If they had something wrong, like, I don't know — they were going to have the Velociraptors come into the kitchen waving forked tongues, like a snake. And I said, "No, you can't do that. No, you've got to do something different."

That's when they changed to the raptor coming up to the window and snorting and fogging it up. That's something only a warm-blooded animal can do.

Live Science: People have griped over the years about inaccuracies in the "Jurassic Park" movies. What would you say to them?

Horner: All of the movies are a series in time. And so you can't really change the way they look. But in "Jurassic World" there's a pretty good explanation when the owner of the park is talking to Dr. Wu [played by actor BD Wong]. He explains that the public wanted scary dinosaurs. Well, Steven Spielberg wanted scary dinosaurs.

Even when [the first] "Jurassic Park" came out, we knew that Velociraptors should have feathers, but at that time, it would have been technically difficult to do it, just from a CG [computer-generated] point of view. And Steven wasn't really too excited about it, anyway.

When I told him they should be colorful and they should be feathered, and he said, "Feathered Technicolor dinosaurs aren't scary enough."

The most accurate dinosaur in all of them is Indominus rex in "Jurassic World." It's a designed dinosaur, so it's perfect.

Live Science: Was there anything you wish had made it into the movie?

Horner: There were lots of things that we tried to get in, like leaving T. rex teeth lying around because they replace their teeth. But it didn't get in there. [Gory Guts: Photos of a T. Rex Autopsy]

Live Science: What do you think of the dinosaur dig at the Liberty Science Center?

Horner: That was fun. I kept telling them, though, the one problem with it is that we don't actually dig a hole to find a dinosaur. The bones are already exposed when we find them. They've weathered down to that point.

So I said, "You should have them all kind of sticking out so that people can see them rather than digging them up. Because that gives the wrong impression of how it actually works."

But kids think that you dig them up. [Here, Horner pointed to the kids.] These are all my graduate students out here.

This interview has been edited and condensed by Live Science.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.