Butchered Mammoth Suggests Humans Lived in Siberia 45,000 Years Ago

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The slashed and punctured bones of a woolly mammoth suggest that humans lived in the far northern reaches of Siberia earlier than scientists had previously thought, a new study finds.

Before the surprising discovery, researchers thought that humans lived in the freezing Siberian Arctic no earlier than about 30,000 to 35,000 years ago. Now, the newly studied mammoth carcass suggests that people lived in the area, where they butchered the likes of this giant animal about 45,000 years ago.

"We now have an enormous extension of the space that was inhabited at 45,000 years ago," said Vladimir Pitulko, a senior research scientist at the Russian Academy of Sciences and co-lead researcher on the study. [Image Gallery: Stunning Mammoth Unearthed]

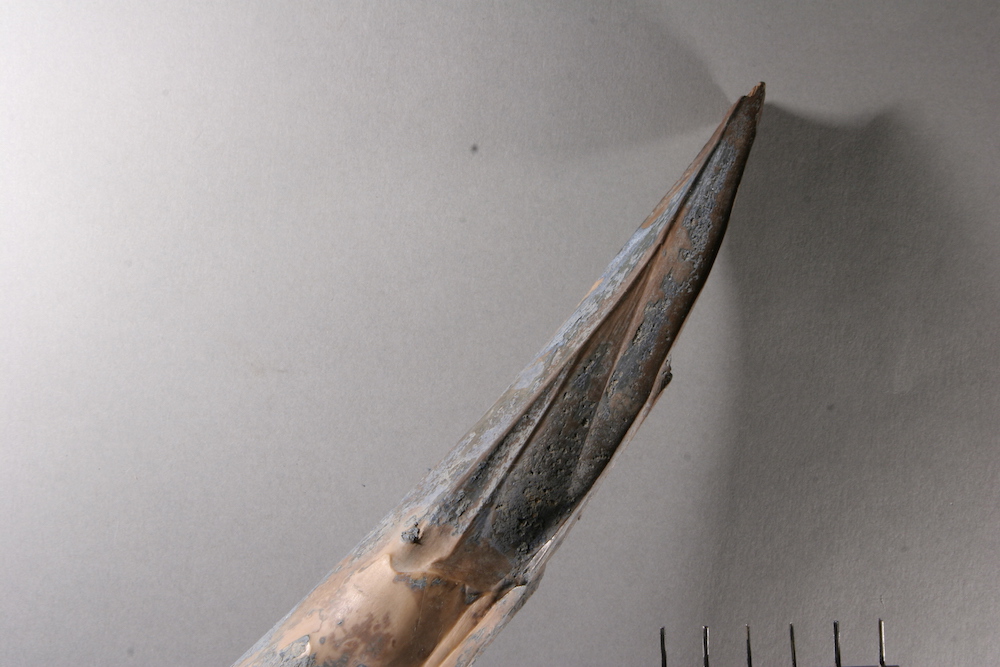

Paleolithic human remains are rarely found in the Eurasian Arctic. But all expectations were overturned in 2012, when a team found the carcass of an "exceptionally complete" woolly mammoth on the eastern shore of Yenisei Bay, located in the central Siberian Arctic, the researchers wrote in the study.

The extreme cold preserved some of the male mammoth's soft tissue, including the remains of its fat hump and its penis, they said.

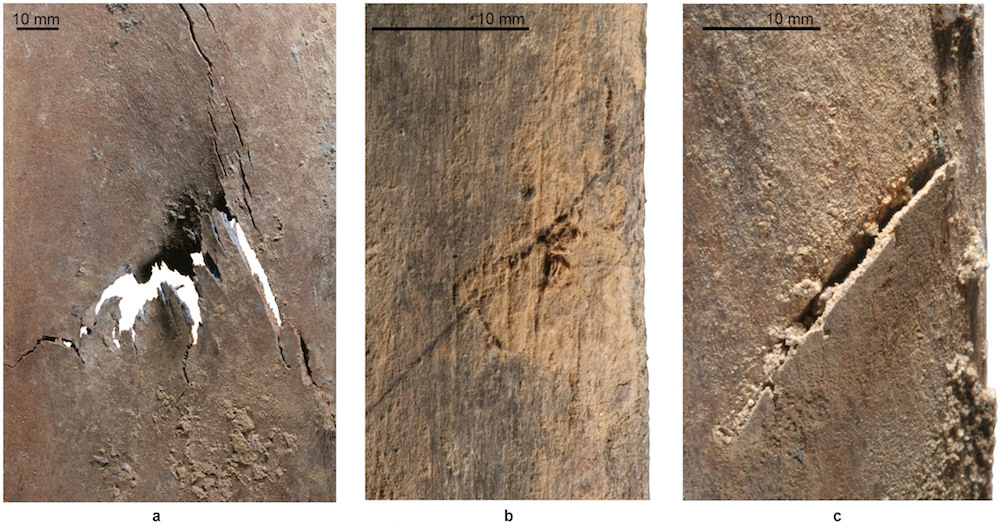

However, injuries found on the mammoth's bones — including its ribs, left shoulder bone, right tusk and cheekbone — suggest that it had a violent end. Some of the bones have dents and punctures, possibly from thrusting spears, the researchers said.

"[These injuries] are clearly related to the death of the animal, which was killed and then partly butchered," Pitulko said in a statement he emailed to journalists.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The ancient hunters likely removed the mammoth's tongue and some of its internal organs, but it's unclear why they didn't take more of the beast.

"Maybe some obstacle appeared and prevented them from returning — who knows?" Pitulko told Live Science.

Bag of bones

Using radiocarbon dating, the researchers dated the mammoth's tibia (shinbone) and surrounding materials to about 45,000 years ago. Radiocarbon dating measures the amount of carbon-14 (a carbon isotope, or variant with a different number of neutrons in its nucleus) left in a once-living organism, and can be used reliably to date material to about 50,000 years ago, although some techniques allow researchers to date older organic objects.

The researchers also found a Pleistocene wolf humerus (arm bone) that had been injured by a "sharp implement with a conical tip," Pitulko said in the statement. The bone, also discovered in Arctic Siberia, dates to about 47,000 years ago, they found.

The wolf bone was uncovered near the bones of ancient bison, reindeer and rhinoceros, all of which have evidence of human modification. This finding suggests that ancient humans hunted and ate a variety of mammals, not just mammoths, Pitulko said. [In Images: Ancient Beasts of the Arctic]

The hunters who butchered the mammoth and wolf were far from the Bering Land Bridge, which lay exposed at that time. However, perhaps their advanced hunting knowledge helped them survive in the Arctic. It may have also helped those who crossed the land bridge survive the journey, Pitulko said.

The new study is "splendidly done," said Ross MacPhee, a curator of mammalogy at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, who was not involved in the new research.

If the mammoth had sustained just one wound, it would have been harder to say it was caused by humans, MacPhee said. For instance, the damaged tusk could be the result of daily mammoth living, he said.

"[But] there's not just the one wound; there's lots of them, and they're quite convincing," MacPhee said.

He added that the mammoth finding is "another nail in the coffin that people exclusively caused the extinctions of these megabeasts."

If people have been hunting mammoths since 45,000 years ago, they would have needed to quickly overhunt them to kill off the mammoths; otherwise, the giants would have likely had enough individuals to continue breeding, MacPhee said.

The study was published online yesterday (Jan. 14) in the journal Science.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus