US Weather Blew Hot and Cold in February

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

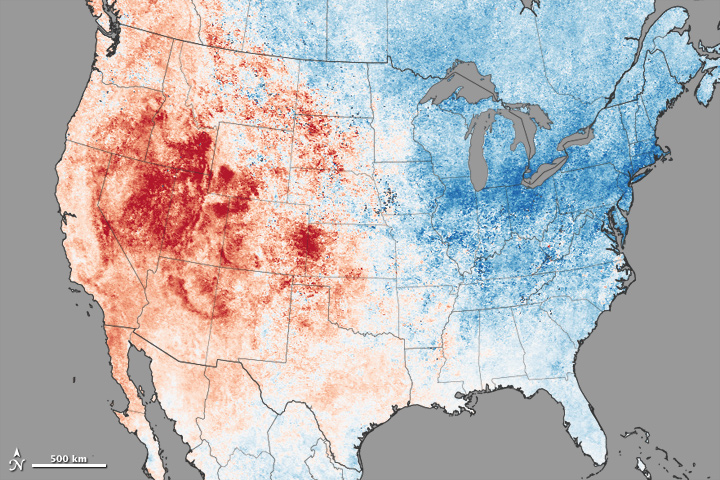

Weather patterns drew a dividing line between the western and eastern United States in February, according to NASA.

While Westerners bemoaned their drought and Easterners complained about snow, the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA's Terra satellite mapped land surface temperatures last month, recording where the temperature rose above and fell below the average. (Land surface temperatures are often warmer than air temperatures.)

The map revealed a temperature break — between record heat and winter's chill — that ran from North Dakota south to Alabama, along the Rocky Mountain foothills.

Although much of the West experienced temperatures that were more than 18 degrees Fahrenheit (10 degrees Celsius) above average, states from the Plains to the Atlantic Coast were 18 F below normal, according to NASA's Earth Observatory.

Although statewide data showed that no state set a new record for cold temperatures in February, many cities broke their all-time winter lows and set new snowfall records to boot. For example, Worcester, Massachusetts, shivered through its coldest February on record, with an average air temperature of 14 F (minus 10 C), and Syracuse, New York, broke its old February record by 3 F (1.6 C), setting a new low of 9.1 F (minus 13 C).

Meanwhile, record-high monthly temperatures were set in California, Nevada, Utah and Washington during the month, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Researchers are looking at several possible causes for the unusual weather patterns seen last month, Mike Halpert, deputy director of NOAA's Climate Prediction Center, told Live Science on March 6. One important player could be the Pacific Ocean, which is much warmer than usual offshore the Pacific Northwest. The warmth may have pushed the jet stream into a position that sucked cold, Arctic air down toward the Northeast and also blocked moisture-laden storms from reaching California.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus