Smash! NASA Drops Huge Helicopter in Safety Tests

To test the safety and efficiency of a giant helicopter, researchers recently dropped one from 30 feet (9 meters) in the air, onto an unforgiving surface of packed dirt.

The crash test — which took place at NASA's Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, earlier this month — was a smashing success, the researchers said. The 45-foot-long (14 m) military helicopter was hauled 3 stories high with cables and then swung to the ground like a pendulum, mimicking the way a helicopter would likely crash in real life.

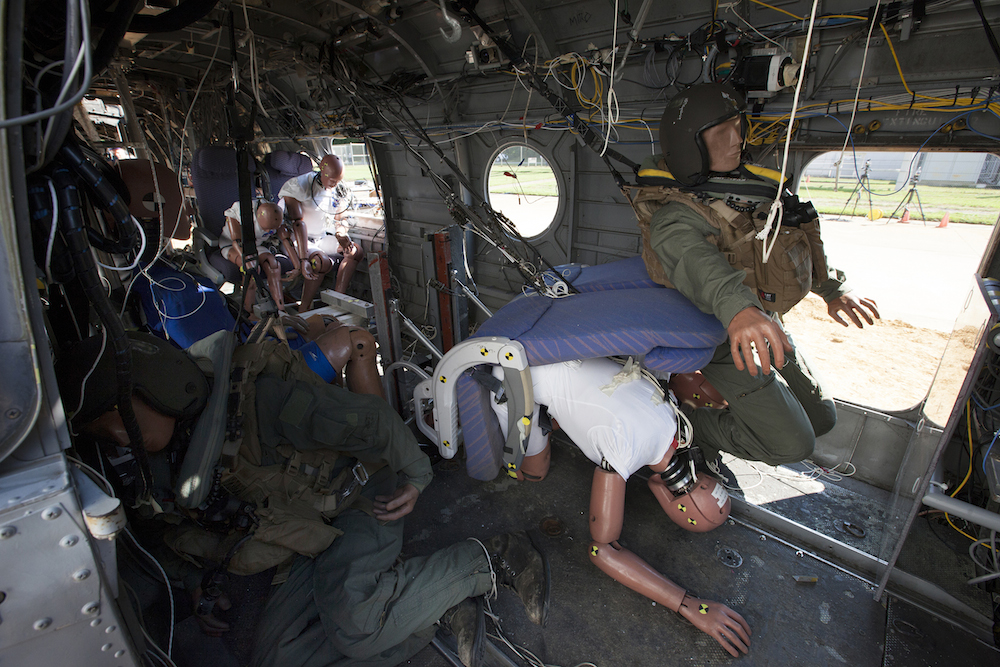

The aircraft hit the ground at 30 mph (48 km/h), what NASA officials say is a severe, but survivable impact speed. Onboard were 13 crash test dummies equipped with instruments that helped record data about the crash, as well as a host of computers that recorded the 10,500-lb. (4,760 kilograms) aircraft's every move. The helicopter was also outfitted with special materials, including flooring and cameras, that were capable of recording even more data from the crash. [Photos: NASA Conducts Crash Test of Chopper Body]

"We removed the metallic floors and added two custom-designed and -built in-house composite subfloors and an Australian-designed subfloor," Justin Littell, a mechanical engineer at NASA who helped conduct the test, said in a statement. "Then we put a window, made out of clear polycarbonate, in the floor and actually focused three of the high speed cameras through the floor into the subfloor to see how these composite energy absorbers crush during the impact."

The high-speed camera technique used by the researchers is known as full-field photogrammetry. To facilitate data tracking with this technique, the outside of the aircraft received an unusual black-and-white, speckled paint job. Each black dot of paint was tracked by one of 40 or so high-speed cameras, which were capable of capturing 500 images per second.

The technique helped the researchers determine the exact spots on the helicopter that cracked, collapsed or buckled during the crash. And the cameras worked well, recording certain phenomena that the researchers weren't expecting.

"One of the things we noticed was there was an excessive shearing action that almost slipped the entire floor, instead of crushing the subfloor like we anticipated," said Martin Annett, lead test engineer for NASA. One of the reasons that NASA performs these types of crash tests on aircraft is that engineers tend to learn unexpected things from such exercises, he added.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

With this plethora of new data in hand, NASA can start putting what they learned from the crash test to good use, said Susan Gorton, manager of NASA's Rotary Wing Project, which leads research efforts for rotary aircraft, such as helicopters and vertical and/or short takeoff and landing (V/STOL) aircraft.

"We are looking for ways to make helicopters safer so they can be used more extensively in the airspace system," Gorton said. "The ultimate goal of NASA rotary wing research is to help make helicopters and other vertical take off and landing vehicles more serviceable — able to carry more passengers and cargo — quicker, quieter, safer and greener."

The project also aims to make helicopters more affordable, said Lindley Bark, lead crash safety engineer for the U.S. military's Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR), which helped conduct the crash test.

"This gives us the opportunity to not only see what happens like we see out in the field at a mishap investigation. It [also] helps us understand what happened, why it happened [and] what contributed to it. That lets us spend our money more cost-effectively to improve our helicopter systems," Bark said.

Follow Elizabeth Palermo @techEpalermo. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus