Surprising Survivor: Little Ancient Reptile Outlived Dinosaurs

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Fossils discovered in South America are evidence of true survivors: a new species of lizardlike reptiles that lived through the event that killed the dinosaurs.

Dubbed Kawasphenodon peligrensis, the newly identified specieslived between 66 million and 23 million years ago in what is now Patagonia. K. peligrensis was a rhynchocephalian, a group of reptiles that was quite diverse worldwide until the end of the Cretaceous Period. Today, only one member of this group, the fearsomely toothed tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) survives. It lives only in New Zealand.

Researchers believed that all other rhynchocephalians died out 66 million years ago in South America, swept away along with the dinosaurs during the mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous. The new fossils contradict that notion. [Wipe Out: History's Most Mysterious Extinctions]

"We thought that they became extinct, but well, here they are," said study researcher Sebastián Apesteguía, a paleontologist at Universidad Maimonides in Buenos Aires.

Surprise survivor

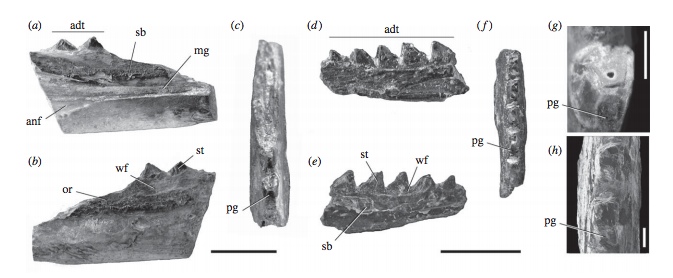

The fossils — two partial jawbones — were uncovered in Argentina's Chubut Province near a place called Punta Peligro. The name means "Point Danger," and for good reason. The beaches there run into sea cliffs and vanish during high tide.

"The access to the locality is several kilometers along the beach to reach the appropriate point," Apesteguía told Live Science. "So if you are late, the sea takes you."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The two jaws were found along with fossils from turtles, crocodiles and well-preserved mammals, Apesteguía said. Each jawbone belonged to an animal that grew to be around 16 inches (40 centimeters) long. The species is in the same genus as another rhynchocephalian from the Cretaceous Period, before the mass extinction, Apesteguía said, revealing continuity in the lineage despite the extinction event. Other animals found at the site, including mammals and turtles, appear to have survived the mass extinction as well, he said.

"We are beginning to understand that perhaps the late Cretaceous extinction was not that hard in South America, or in the Southern Hemisphere, as it was in the Northern Hemisphere," Apesteguía said.

Life and death

Why the Southern Hemisphere might have been less hard-hit remains a mystery, as does much of the daily life of K. peligrensis. Rhynchocephalians came in a variety of shapes and sizes, with some species growing as large as 5 feet (1.5 meters) long,Apesteguía said. The newfound species lived in a littoral, or shoreline environment. Researchers aren't even sure if it was aquatic living or a land-dweller, nor do they know what it ate. Various rhynchocephalian species were herbivores, omnivores or insectivores, Apesteguía said, and the new species has ambiguous teeth.

Despite its survivor status, K. peligrensis eventually died out in South America. Most likely, the extinction occurred about 33.9 million years ago, during the Eocene-Oligocene extinction event, Apesteguía said. At this time, climate cooled dramatically, affecting species across the globe.

The researchers reported their findings today (Aug.19) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitterand Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus