Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

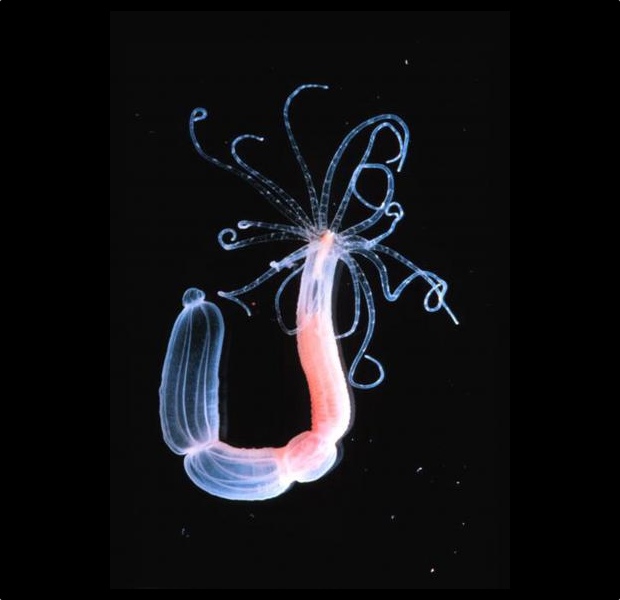

The sea anemone is an oddball: half-plant and half-animal, at least when it comes to its genetic code, new research suggests.

The sea creature's genes look more like those of animals, but the regulatory code that determines whether those genes are expressed resembles that in plants, according to a study published Tuesday (March 18) in the journal Genome Research.

What's more, the complicated network of gene interactions found in the simple sea anemone resembles that found in widely divergent, more complex animals.

"Since the sea anemone shows a complex landscape of gene regulatory elements similar to the fruit fly or other model animals, we believe that this principle of complex gene regulation was already present in the common ancestor of human, fly and sea anemone some 600 million years ago," Michaela Schwaiger, a researcher at the University of Vienna, said in a statement. [See Stunning Photos of Glowing Sea Creatures]

A simple plan

The size of an organism's genome doesn't correspond to how simple or complex that creature's body is, so some scientists hypothesized that more complicated links and networks between genes made for more sophisticated body plans.

Schwaiger and her colleagues at the University of Vienna analyzed the genome of the sea anemone, not only identifying genes that code for proteins, but also assessing snippets of code known as promoters and enhancers, which help turn the volume up or down on gene expression.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team found the sea anemone's simple anatomy hides a complicated network of gene interactions, similar to those found in higher animals such as fruit flies and humans. That belies the notion that more complex gene networks always correlate with more elaborate body plans, and also suggests the evolution of this level of gene regulation happened before sea anemones, fruit flies and humans diverged, about 600 million years ago.

Part plant

The team also found the sea anemone had a second level of regulation that closely resembles one found in plants. Genes are transcribed or copied by a RNA, which is then used as a recipe to build proteins. But tiny snippets of genetic material called microRNAs, which bind to the RNA copies, can stop the step of protein assembly.

While plants and animals have microRNAs, they look and act very different, so researchers had assumed they arose independently in the two kingdoms. Schwaiger and her colleagues found the microRNAs in the sea anemone have similarities to those found in both plants and animals.

That suggests these microRNAs probably evolved before plants and animals diverged long ago, and provides an evolutionary link between plant and animal microRNA.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus