Ancient 'Snowball Earth' Possibly Triggered by Rock Weathering

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

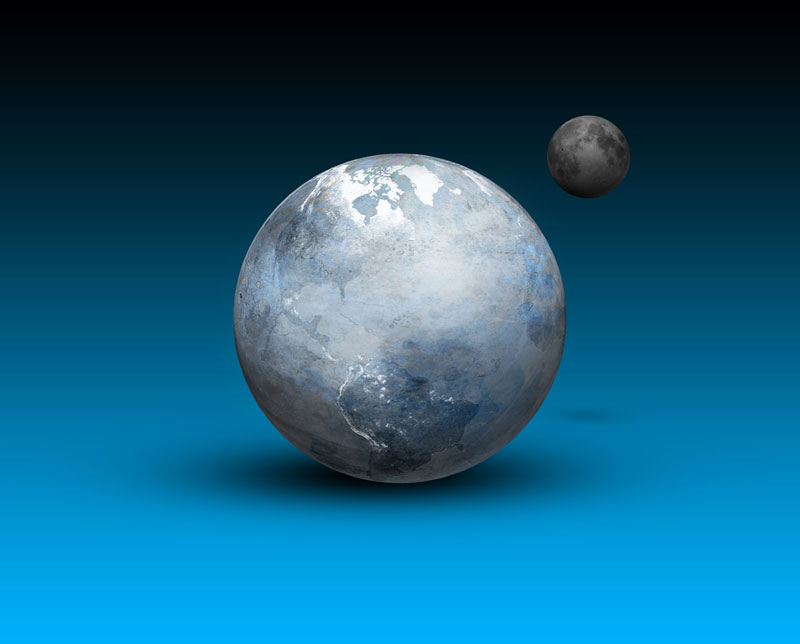

A global ice age that lasted more than 50 million years may have been triggered by volcanic rocks trapping carbon dioxide that would otherwise warm the planet, researchers say in a new study detailed today (Dec. 16) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Although ice is now found mostly in Earth's polar regions, analysis of ancient rocks suggests it could at times cover the entire globe. The causes of these "snowball Earth" periods remain mysterious, with the cause of one episode 2.3 billion years ago perhaps being the widespread emergence of oxygen in the atmosphere, which destroyed greenhouse gases keeping Earth warm.

For the new study, scientists focused on a snowball Earth period that began about 717 million years ago known as the Sturtian glaciation. This global ice age was preceded by more than 1 billion years without glaciers, making the Sturtian a transition from a longtime ice-free world to a snowball Earth, the most dramatic episode of climate change in the geological record.

The researchers noted the Sturtian broadly coincided with rifts tearing apart the ancient supercontinent Rodinia, as well as major volcanic activity in equatorial regions. This suggested the Sturtian might have its roots in tectonic activity.

The scientists investigated ancient rocks in the Mackenzie Mountains of northwest Canada known as glaciogenic diamictites, which are sedimentary rocks that are deposited by glaciers as they move over the Earth. They analyzed rocks both above and below these glaciogenic deposits to find out the deposits' ages.

"For me, this type of work combines the best parts of geology — fieldwork in remote and beautiful places, such as the Mackenzie Mountains of northern Canada, and working in a geochemistry lab," said study lead author Alan Rooney, a geologist at Harvard University. "The fieldwork is crucial to provide context for any data you may generate in the lab."

Specifically, the researchers analyzed levels of the elements rhenium and osmium within the sedimentary rocks bracketing the glaciogenic deposits. Rhenium breaks down via radioactive decay, generating osmium over time. By analyzing the ratios of rhenium and osmium isotopes within the rocks, the investigators could determine their age. (Isotopes are different forms of elements, where the atoms have different numbers of neutrons in their nuclei.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The scientists found the Sturtian lasted about 55 million years.

"The most surprising aspect of these results is the duration of this glacial epoch," Rooney told LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

The researchers also investigated osmium and strontium isotopes within rocks before, during and after the Sturtian. The levels of various isotopes in rocks depends on whether or not they came from radioactive sources such as eroded volcanic rock.

Based on their analysis, the researchers suggest a "fire and ice" scenario cooled the planet. As volcanic rock that erupted before the Sturtian eroded, it absorbed carbon dioxide, trapping it within sediments that washed into the oceans. Carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas that traps heat — by removing it from the atmosphere, global cooling resulted.

Future research can analyze whether the Sturtian was one long-lasting snowball or a series of glacial and warmer periods with one final global snowball, Rooney said. Research can also investigate the environment right before the Sturtian to unearth even more details about its development.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus