Homo erectus: Facts about the first human lineage to leave Africa

Homo erectus is associated with a number of firsts in its 2 million years of existence, including being the first hominin to travel out of Africa.

Name: Homo erectus

Dates: 2 million to 108,000 years ago

Locations: Africa, Europe, Asia and Oceania

Notable firsts: First hominin species to leave Africa

Compared with modern humans (Homo sapiens), who have been around for the past 300,000 years, Homo erectus, or "upright human," had a long reign. The ancient human species lived from 2 million years ago until about 100,000 years ago, nearly the entire Pleistocene epoch, which included the last ice age. Fossils also show that H. erectus lived across the globe, including in what are now the countries of South Africa, Kenya, Spain, Georgia, Romania, China and Indonesia.

H. erectus had a similar range of body sizes to modern humans, and it is the first human lineage to have limb-and-torso proportions similar to those of modern humans rather than similar to apes'. This suggests H. erectus had adapted to walking on two feet and, similar to modern humans, used tools, technology and culture to survive.

"There are a lot of firsts associated with Homo erectus," Karen Baab, a biological anthropologist at Midwestern University in Glendale, Arizona, told Live Science. "We have the first evidence of hominins outside of Africa, the first evidence of Acheulean [hand-ax] tool use, more consistent evidence of hunting and access to meat, a broader dietary range, and a wider range of ecological habitats," she said. "We just see a lot more going on, and that's interesting."

What is the evolutionary history of Homo erectus? Where did Homo erectus live?

The first H. erectus fossil to be found was a 1 million-year-old skull discovered by Dutch surgeon Eugène Dubois in Indonesia in 1891. But the lineage and evolutionary history of H. erectus and other Homo species are unclear and have been muddied further by recent finds.

H. erectus was once thought to have first evolved from an earlier human ancestor, known as Homo habilis, somewhere in East Africa. It was thought that H. erectus then spread to inhabit South Africa, parts of Europe (Spain and Italy), the Caucasus, India, China and Indonesia.

However, there's much disagreement about whether all of these populations are actually H. erectus or if they should be considered other species.

According to Adam Van Arsdale, a biological anthropologist at Wellesley College, some experts favor the use of the species name H. erectus for fossils found in Central and East Asia and Homo ergaster for those from Africa and West Asia. Further splits have been suggested as well, with some researchers calling West Asian fossils Homo georgicus and some calling fossils from Europe Homo heidelbergensis. However, while scientists have pointed out subtle anatomical differences among these groups, including a slightly larger brow ridge in H. ergaster, there are no major differences that could indicate a separate species.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But if we imagine H. erectus as one species, "then there's no getting around the fact that there is regional variation and temporal variation," Baab said.

Scientists also disagree about whether H. erectus is a direct ancestor of H. sapiens.

"I would put it as an ancestral to living humans," Van Arsdale said. "That doesn't mean that every fossil is an ancestor to humans, but the species as a whole is." In other words, our species likely evolved from H. erectus ancestors, but H. erectus persisted long enough to potentially interact with H. sapiens.

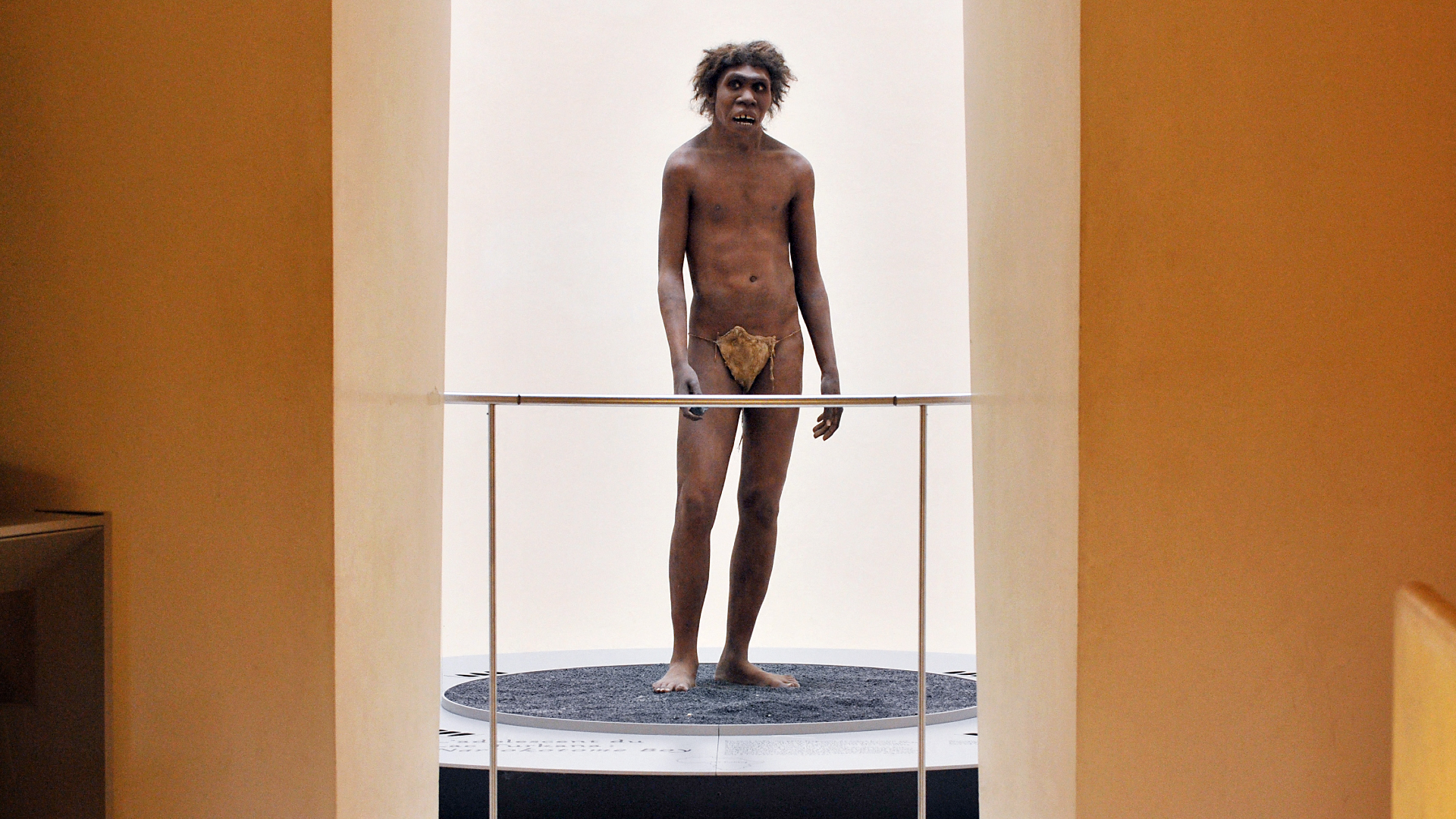

What did Homo erectus look like?

H. erectus had similar overall body proportions to modern humans, but its height, body mass and brain size varied dramatically.

For instance, one of the most complete fossil H. erectus individuals ever found, a 1.5 million-year-old skeleton of an adolescent male known as Nariokotome Boy (previously Turkana Boy), was 5 feet, 3 inches (1.6 meters) tall when he died. But he may have grown up to 6 feet, 1 inch (1.85 m) tall as an adult, though other estimates put his maximum height at a more modest 5 feet, 4 inches (1.63 m). By comparison, the iconic 3.2 million-year-old Australopithecus skeleton dubbed Lucy was just 3 feet, 7 inches (1.1 m) tall at death, according to a 1988 study.

Estimating the body size of early H. erectus is complicated, however, due to the longevity of the species and its geographic spread. "The first bodies outside of Africa are not that big," Baab said. "They are not quite like modern humans; they're on the smaller end."

The earliest fossils of H. erectus discovered outside Africa are from two sites in the Republic of Georgia, called Dmanisi and Orozmani, which date to about 1.8 million years ago. More than 100 bones have been recovered from Dmanisi, including several complete skulls. Researchers have learned that the Dmanisi individuals were short, ranging from 4 feet, 10 inches to 5 feet, 5 inches tall (1.45 to 1.66 m), and had small brains, long faces and large teeth.

Average brain size calculations for H. erectus are also complicated. "One definite pattern we see is an increase in brain size over the geological span," Baab said. The earliest H. erectus fossils from South Africa and Dmanisi have distinctly smaller brains than the fossils from later sites in Indonesia. "In between, there's quite a bit of variation," she said.

In general, small-bodied, early H. erectus fossils had brain sizes not much bigger than that of Australopithecus (an ancestor of the Homo genus that includes Lucy), according to Van Arsdale, but the Nariokotome Boy and other early, large-bodied specimens had a brain volume more than 50% larger than Australopithecus and about 60% to 75% the volume of people living today.

Those bigger brains and bodies required more food and energy to survive. Molecules from food an individual consumes naturally become incorporated into growing teeth and bones, so analyses of the dental micro-wear and stable isotope chemistry of H. erectus fossils suggest it ate a fairly flexible and diverse diet, which likely included a lot of animal protein, according to a 2011 study.

Homo erectus behavior and culture

H. erectus' larger brain may explain its apparent intelligence. "They were very successful in a lot of different environments," Van Arsdale said. But experts are still debating whether H. erectus could control fire, cook food and create art.

H. erectus used a variety of stone tool types, and evidence suggests they were crafting hippo and elephant bones into tools as well. A 2013 analysis of stone hand axes revealed that H. erectus was butchering animals by at least 1.75 million years ago. Additionally, more recent research on animal bones with stone tool cut marks suggests H. erectus may have been living in what is now Romania 1.95 million years ago and butchering animals for their meat. However, no fossils have been found to prove the marks were made by a hominin.

Evidence for cooking is even less clear. A 2011 study suggested H. erectus (and potentially other, earlier Homo species) may have harnessed fire to cook food as early as 1.9 million years ago. But with no hearths, it's hard to know if burned bones indicate control of fire or naturally occurring wildfires, Baab said. Possible hearths and burned fish bones were discovered in 2022 at a 780,000-year-old site in Israel, however, suggesting H. erectus may have been cooking fish.

Unlike Neanderthals — our ancient cousins who are thought to have created intentional engravings, symbolic fingerprints and carved bones up to 130,000 years ago — H. erectus is not generally considered to have created art. There are two possible pieces of evidence, however, to suggest that H. erectus was more capable than previously assumed.

In a 1958 study, Louis Leakey discovered lumps of red ocher at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, possibly associated with the skullcap of H. erectus. Chunks of ocher that have been shaped with stone tools are often considered symbolically important to early H. sapiens and may have been to H. erectus as well.

In a 2014 study, researchers discovered 540,000-year-old shells — which may be the oldest engravings ever found — associated with H. erectus, as well as shells that were apparently used as tools. Many of the shells discovered at this site on the Indonesian island Java contained unnatural holes near the shells' hinges, exactly at the point where muscle keeps the shell closed. This suggests H. erectus may have purposely drilled these holes to easily open the shells and eat the mollusks, before using the shells as tools and canvasses, according to the researchers.

When did Homo erectus go extinct?

Researchers have long been fascinated by the disappearance of Neanderthals from Europe around 40,000 years ago, but far less research has investigated what happened to H. erectus.

The current best evidence for H. erectus' "last stand" comes from the site of Ngandong on the island of Java in Indonesia. Nearly a century ago, excavations in a bone bed uncovered 12 skullcaps and two lower leg bones from H. erectus. Based on multiple dating techniques, researchers proposed that the bone bed accumulated sometime between 117,000 and 108,000 years ago. Although these dates give a clear indication of when H. erectus as a distinct species died out, researchers don't know what happened.

"When we think about the range of Homo erectus from South Africa through east and probably North Africa, into Europe, over to China, and down into Indonesia, the likelihood that there was one explanation that would account for all of those groups' demise seems unlikely," Baab said. "I imagine they got outcompeted in many cases by more modern hominins, and I imagine there was some interbreeding that happened along with that."

Just as Neanderthals left genetic traces in people outside Africa, H. erectus may have left its DNA in people living today.

A small collection of studies published in 2025 argues just that, suggesting that H. erectus met up with our H. sapiens ancestors in Asia. In May 2025, researchers announced that they had discovered 140,000-year-old H. erectus bones off the coast of Java. But they also found evidence that this group was hunting turtles and cow-like animals — a behavior previously unknown in H. erectus. The study's lead author, Harold Berghuis, previously told Live Science that the hunting behavior might have been a result of cultural exchange with H. sapiens.

And in a study published in the September 2025 issue of the Journal of Human Evolution, researchers looked at 21 teeth from a mystery human that lived 300,000 years ago in China. The team found that these teeth had a mix of ancient and modern traits. One possible explanation for the unique combination is that H. erectus and H. sapiens were having babies together, the researchers noted in the study.

So far, no preserved H. erectus DNA has been found. But the study of ancient proteins, called paleoproteomics, has the potential to recover genetic information from fossils that are millions of years old. This technique might help researchers fill in the gaps in the human story and better understand H. erectus' role in it.

Editor's note: This article was originally published June 22, 2015, and was updated Sept. 5, 2025 to include the latest research on Homo erectus.

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.