Fracking Wastewater Radioactive and Contaminated, Study Finds

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, extracts oil and gas from deep underground by injecting water into the ground and breaking the rocks in which the valuable hydrocarbons are trapped. But it also produces wastewater high in certain contaminants — and which may be radioactive.

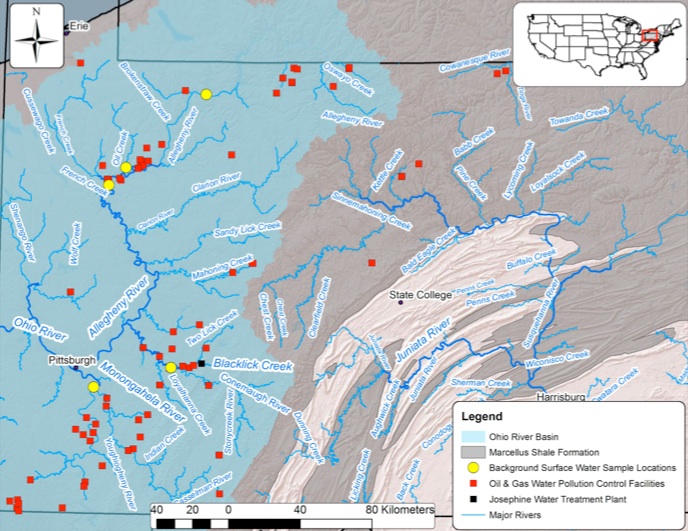

In a study published today (Oct. 2) in the journal Environmental Science and Technology, researchers found high levels of radioactivity, salts and metals in the water and sediments downstream from a fracking wastewater plant on Blacklick Creek in western Pennsylvania.

Among the most alarming findings was that downstream river sediments contain 200 times more radium than mud that's naturally present upstream of the plant, said Avner Vengosh, a co-author of the study and a professor of geochemistry and water quality at Duke University. Radium is a radioactive metal naturally found in many rocks; long-term exposure to large amounts of radium can cause adverse health effects and even diseases like leukemia. [5 Everyday Things that Are Radioactive]

Contaminated waters

The concentrations of radium Vengosh and his team detected are higher than those found in some radioactive waste dumps, and exceed the minimum threshold the federal government uses to qualify a disposal site as a radioactive dump site, Vengosh told LiveScience. While the Josephine Brine Treatment Facility removes some of the radium from the wastewater, the metal accumulates in the sediment, at dangerously high levels, he added. Radium can make its way into the food chain by first accumulating in insects and small animals, and then moving on to larger animals, like fish, when they consume the insects and smaller animals, Vengosh added. But it's not known to what extent this is happening, since this study didn't address that question, he said.

For two years, the team monitored sediments and river water above and below the treatment plant, as well as the discharge coming directly from the plant, for various contaminants and levels of radioactivity. In the discharge and downstream water, researchers found high levels of chloride, sulfate and bromide.

Levels of salinity in the plant's discharge were up to 200 times higher than what is allowed under the Clean Water Act — and 10 times saltier than ocean water, Vengosh said. But fracking wastewater is exempt from that law, Vengosh said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The high bromide concentrations that were found were particularly concerning, since bromide can react with chlorine and ozone — which is used to disinfect river water and produce drinking water — to yield highly toxic byproducts. But there's no direct evidence that this has happened yet, Vengosh said.

Several of these contaminants, particularly radium and bromide, may be present in high enough concentrations to cause harm to human health and the environment, but that wasn't addressed in this study, Vengosh said.

'Alarming'

"The occurrence of radium is alarming — this is a radioactive constituent that is likely to increase rates of genetic mutation" and poses "a significant radioactive health hazard for humans," said William Schlesinger, a researcher and president of the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, in Millbrook, N.Y., who wasn't involved in the study.

Researchers say they are sure the contaminants are coming from fracking because the Josephine facility treats this oil and gas wastewater, and the water contains the same chemical signature as rocks in the Marcellus Shale Formation, Vengosh said. This wastewater is often called "flowback," as it's the water that flows back to the surface from underground after being injected into rocks in the fracking process.

In Pennsylvania, some of this water is transported by oil and gas companies to treatment locations like the Josephine facility, where it is processed and released into streams and rivers. However, much of the water used in fracking is treated by oil and gas companies and reused, or injected into deep wells, said Lisa Kasianowitz, an information specialist at the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP).

The treatment facility did remove some contaminants, including some of the radium, though enough made it through to accumulate in high levels in sediments, Vengosh said. It also "did nothing" to remove certain salts, like bromide, he said. Traditional wastewater plants are not built to remove these contaminants, he added.

The study "really seals the verdict that it's flowback waters that are contaminating the streams," Schlesinger told LiveScience.

The Pennsylvania DEP confirmed that the Josephine facility is accepting and discharging "conventional oil and gas wastewater in accordance with all applicable laws and regulations," Kasianowitz said.

Vengosh said that the research suggests that similar contamination may be happening in other locations with discharge of fracking wastewater throughout the Marcellus Shale formation, which underlies parts of Pennsylvania, New York and Ohio.

Email Douglas Main or follow him on Twitter or Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebookor Google+. Article originally on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus