First Estuary Discovered Under Antarctic Ice

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Some of the richest ecosystems on Earth are estuaries, where freshwater and saltwater collide with the tides. For the first time, scientists have discovered an estuary beneath Antarctica's massive ice sheet.

A strange and singular ecosystem could exist in the estuary, hidden at the head of the thick Ross Ice Shelf in West Antarctica. (Ice shelves are floating platforms that form where glaciers or ice sheets flow onto the ocean.)

"We know in the subaerial environment that estuaries are fascinating," said Richard Alley, a glaciologist at Penn State University and co-author of a study reporting the find. "[Here] you've got a mixture of two very strange environments, so whether you're going to find anything that shakes up the world, I don't know, but it's a fascinating target."

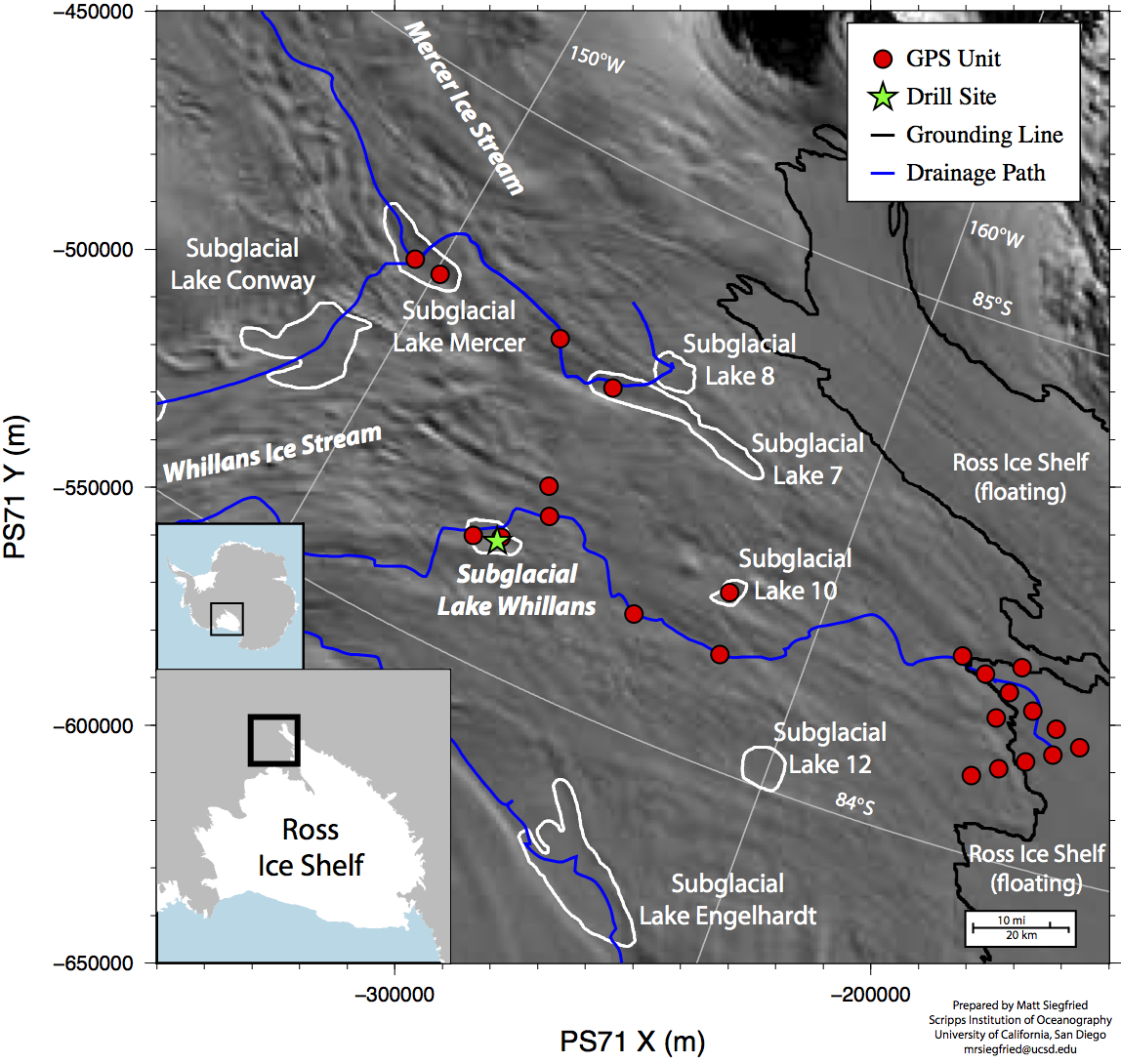

The tidal mixing zone sits beneath the end of the Whillans Ice Stream, one of the fast-moving "ice rivers" in West Antarctica. Ice streams are features that flow quickly compared to the surrounding ice. If the name Whillans rings a bell, it might be because of Lake Whillans: Earlier this year, researchers announced the buried glacial lake contained microbial life. [Antarctic Album: Drilling Into Subglacial Lake Whillans]

Estuaries are channels only partly open to the ocean, and a 1-kilometer-wide (0.6 miles) channel snakes inland from the Ross Sea toward Lake Whillans, Alley and his co-authors reported Sept. 6 in the journal Geology. The riverlike channel is about 7 meters (23 feet) deep.

As with open-air estuaries, the mixing zone between glacial meltwater and seawater extends a few miles upstream. The research team, led by Huw Horgan of Victoria University in New Zealand, found signs of athin brackish layer of subglacial water, ocean water and sediment several kilometers inland of the Whillans Ice Stream grounding line. The grounding line is where the bottom of a glacier loses contact with land and floats on water.

Though tides can drive saltwater many miles inland, there is no contemporary geochemical evidence for a connection between the sea and Lake Whillans, said John Priscu, who leads the Lake Whillans microbiology team but was not involved in this study. But based on the chemistry of Lake Whillans, the water flowing downstream could provide nutrients to the estuary, leading to relatively high bacterial productivity and elevated levels of diversity, said Priscu, a polar ecologist at Montana State University.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

An ambitious science expedition this year may reveal what's living in the estuary. Researchers plan to drill through more than a half-mile (1 kilometer) of ice and examine the Ross Ice Shelf grounding line with a remotely operated vehicle.

Alley predicts the estuary discovery will send researchers hunting for similar channels elsewhere in Antarctica. The continent has a complex drainage network, with more than 300 subglacial lakes that occasionally release roaring floods. Glacial modelers have generally thought that the subglacial water poured into the ocean waterfall-style, with saltwater and freshwater always separated. Instead, it's likely that researchers will find a range of discharges, from waterfalls to estuaries, Alley said.

"The odds are good that everything in between exists," he said.

A deeper connection between the ocean and Antarctica's subglacial streams will mean revising models of how the ice sheet ebbs and flows. For example, studies show the Whillans Ice Stream retreated very quickly from its former grounding line thousands of years ago. (Whillans has a strong attachment to its current grounding line.) Scientists want to know how that happens, and why. An estuary provides a way for warm seawater to get behind the grounding line.

"We're at the point where we're finding out the mechanisms that give this very strange sort of behavior," Alley said, referring to the rapid retreat. "Places like this channel, where water can get behind that strong edge, point at a mechanism," he said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus