Large Antarctic Crater Created by Underground Flood

The buried lakes under Antarctica's ice cap can unleash massive floods, just like glacial lakes on land, scientists are starting to realize. One recent deluge sent as much water as is in Scotland's Loch Ness flowing under the East Antarctic Ice Sheet, near the Cook Ice Shelf, a new study reports.

Nearly 380 lakes have been discovered under Antarctica's ice, including one with microbial life. Radar and seismic studies that penetrate ice have revealed complex waterways that feed and drain the lakes. Researchers are keen to discover how the streams and floods affect ice flow, especially as modelers try to predict how the frozen continent will respond to climate change.

"You're periodically getting these huge events beneath the ice sheet, these massive floods, and that sort of information will be useful to people who are building models of how the ice is responding to the environment," Malcolm McMillan, lead author of the new study and a geophysicist at the University of Leeds in the U.K., told LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

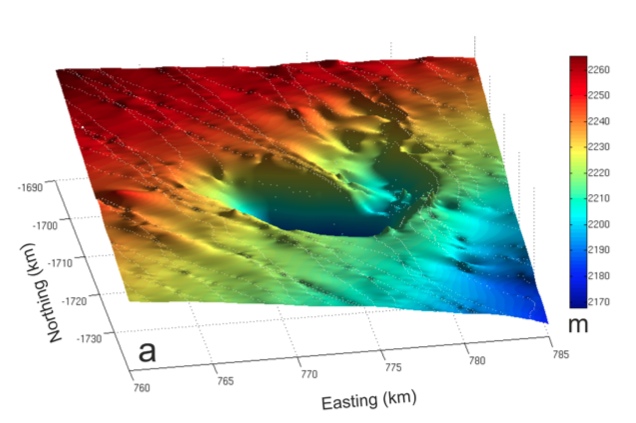

While scientists are still figuring out what triggered the recent flood, one of the largest ever seen, they know how much water flowed from the buried glacial lake because of the giant crater it left behind. The surface of the ice sank as the lake water disappeared, a shift detected by the European Space Agency's CryoSat-2 satellite. The findings were published online June 23 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. [Video: Antarctica: Solving Geologic Mysteries]

During an 18-month period starting in 2007, Cook subglacial lake drained with an outflow twice as fast as Britain's River Thames at its peak, McMillan said. The total water volume lost was about 1.5 cubic miles (6 cubic kilometers).

The crater left behind covers an area of about 100 square miles (260 square km), and is about 230 feet (70 meters) deep at its lowest point.

Since 2008, the crater's surface has slowly inflated, a sign that ice or water has occupied the space left by the flood. The researchers plan to figure out whether it's fresh or frozen water (ice) that's filling the void. They're also modeling whether ice or sediment may have dammed the lake, leading to the flood.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"There's a lot of mystery surrounding the continent still that we don't understand," said Hugh Corr, a study co-author and glaciologist with the British Antarctic Survey. "This will be modeled in terms of the ice dynamics and the thermal impacts of this feature, and that will add to the general knowledge of the continent."

As of yet, there are no signs that the floodwaters have reached the ocean. In the past, subglacial lake floods have lifted up the ice further downstream, while others showed no signs of disturbing the ice.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.