New Look at What Lies Beneath Hawaii

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

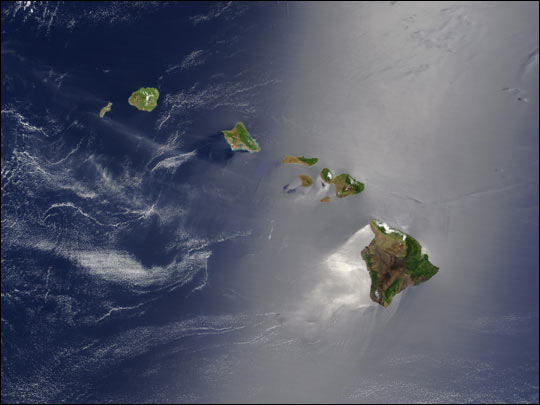

The hotspot feeding Hawaii's volcanoes may look like one of two lava lamp bubbles — an oval blob or a long, stretched-out plume.

With direct access to the mantle still the stuff of science fiction, scientists have argued for decades about the shape and size of Hawaii's hotspot. Is it shallow, or does it rise from deep in the Earth? Now, a new look under the islands seems to refute the shallow mantle model.

To come up with the new picture, researchers used seismic waves from earthquakes to detect temperature differences within the mantle, similar to a CT scan. The waves travel faster through cold rock and slower through hot rock. The mantle is the thick layer of hot rock between Earth's crust and core.

The picture revealed hotter temperatures underneath and southeast of the Big Island of Hawaii, said Anna Courtier, a seismologist at James Madison University in Virginia. "We see this localized area relatively deep in the mantle that appears to be associated with increased temperature," she said. "This is consistent with the idea of a relatively deep-seated mantle plume," she said.

For at least 300 miles (500 kilometers) below Hawaii, the mantle is hotter than the surrounding rock. That indicates the plume comes from a relatively deep source, though the data doesn't allow the team to peer deeper into the mantle, near the core. The temperature is about 600 degrees Fahrenheit (325 degrees Celsius) higher in this region compared with the average mantle, Courtier said.

"We can't tell whether it extends down to the core or not, but it doesn't rule it out. It does rule out a shallow source with no thermal plume whatsoever," Courtier told LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

The deepest spot is beneath and southeast of the Big Island of Hawaii, nearest the most recent volcanic activity at Kilauea and Mauna Loa. At 185 miles (300 km) in girth, the diameter of the plume is a bit broader than seen in previous studies.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new study was published July 1 in the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus