On the Brink: Climate Change Endangers Common Species

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A wide variety of plants and animals are likely to become much less common if something isn't done to avert the worst effects of a warming climate, new research suggests.

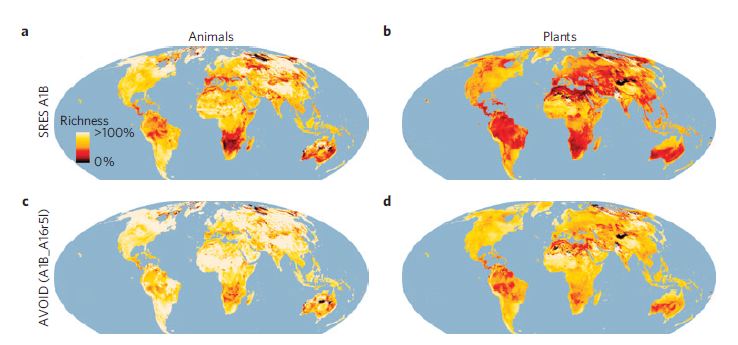

Under a "business as usual" scenario, where greenhouse gas emissions aren't significantly reduced, about 50 percent of plants and one-third of animals are likely to vanish from half of the places they are now found by 2080, said Rachel Warren, a researcher at the University of East Anglia in England. These losses could lead to local extinctions of species.

In the study, published online today (May 12) in the journal Nature Climate Change, researchers looked at the likely effects of global warming on 50,000 different species around the world. The study used a computer model that calculated the desired climatic zone that these plants and animals live in, and analyzed how these zones, and the organisms' accompanying ranges, are likely to shift in the future, Warren told OurAmazingPlanet. [8 Ways Global Warming is Already Changing the World]

In many cases these shifts are likely to cause extinctions, as warming temperatures force animals and plants to move to points beyond which they cannot go, such as up mountaintops and toward coastlines into the ocean, Warren said.

However, plants and animals with limited ranges were intentionally excluded from this study, because the goal was to gauge climate change's effects on common species, Warren said. In other words, if you include total extinctions — which this study did not — the impact of climate change on global biodiversity looks even worse.

Not too late

It's not too late to do something to prevent the widespread loss of species, however. The study found that if emissions are slowed and ultimately begin being reduced by 2017, about 60 percent of the losses can be avoided, Warren said. If emissions peak in 2030 and are reduced after that, about 40 percent of the losses could be avoided.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The losses are likely to be particularly severe in Central and South America, Australia, North Africa and Southeast Asia, Warren said. These areas are vulnerable to declines in rainfall and increasing temperatures, according to the study.

A decline in plants and animals means a decline in the services these organisms provide, such as recycling of nutrients, purification of air and water, pollination, as well as draws for ecotourism and recreation, she added.

Some species are likely to be more tolerant than others, but the point of this study is that it didn't focus on any one plant or animal, or specific high-profile creatures like polar bears, Warren said. "The important message I want to get across is that there are large effects on a large proportion of species," she said.

Warren said she considers the estimates conservative, since the study didn't take into account interactions between animals and plants, which could exacerbate declines; if an animal's preferred plant food disappears, it too could bite the dust. The research also didn't consider the effect of extreme weather that many models project will become worse with global warming, she said.

"There will be winners and losers in the natural world as species respond to climate change," said Lee Hannah, a senior fellow in climate change biology at Conservation International, who wasn't involved in the research. "This study shows that we can greatly reduce the losers among common, well-known species by taking action to reduce climate change."

This "phenomenal" study "scared me to death," said Terry Root, a scientist at Stanford University who wasn't involved in the research. "What it is showing is how many species we are actually affecting by putting carbon dioxide in the atmosphere," she told OurAmazingPlanet.

Email Douglas Main or follow him on Twitter or Google+. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook or Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus