Scientists Discover San Andreas Fault's Soft Spot

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

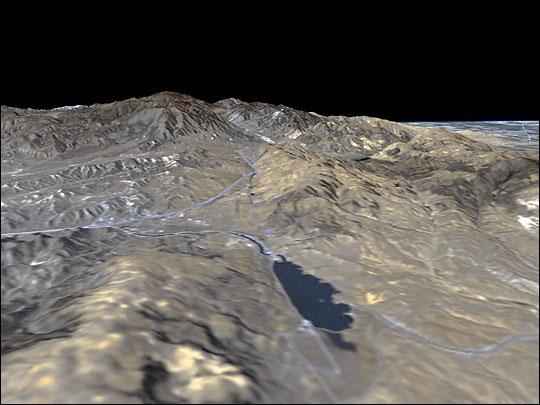

New data from a deep borehole that crosses the San Andreas Fault shows that the monster earthquake-maker has a soft center and it's made of clay. This is the first time researchers have been able to rule out other reasons for the San Andreas' unusual behavior in part of California.

At the north and south, the San Andreas Fault is locked up prone to earthquakes near San Francisco and Los Angeles . However, near Parkfield, Calif., about 200 miles (320 kilometers) northwest of Los Angeles, the fault is creeping, or moving slowly.

"This is a special part of the San Andreas fault," said U.S. Geological Survey scientist David Lockner, an author of a new study on the fault. "It seems weak enough that it slides slowly and continuously, rather than in a jerky motion."

To study what was causing the slip-and-slide motion of the fault, researchers worked at the San Andreas Fault Observatory at Depth to drill down several miles into the fault. Lockner said the site was selected because it experiences repeating earthquakes small earthquakes that measure about 1 to 4 on the Richter scale and occur over and over at regular intervals.

"They're actually shallow enough to reach them at the drill site," Lockner told OurAmazingPlanet. While the team hasn't been able to drill directly into one of these earthquakes yet, they were able to bring up material from the fault zone, about 1.7 miles (2.7 km) below the surface, where the temperature is a whopping 239 degrees Fahrenheit (115 degrees Celsius).

The stuff the researchers brought up from below the ground confirmed that the area was indeed a weak spot in the fault.

Lockner said that there are many mechanisms that can cause weakness from pore fluid pressure that lubricates rock to frictional heating (the warming that occurs when material rubs together) to slippery materials. The reason for weakness on this part of the San Andreas? Weak clays, especially a magnesium-rich clay mineral called saponite.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Using the clays they found in the San Andreas, the researchers were able to re-create in the lab the constant sliding that goes on in the weak part of the fault.

Lockner said this new research, detailed online March 23 in the journal Nature, is just part of a large, international effort to better understand the mechanisms that cause earthquakes.

"This is one part of a broad effort to understand the properties of the San Andreas system. While we're concentrating on the lab measurements, there are others working on field measurements," he said. All of the information will help seismologists better grasp what is controlling earthquakes, from the inside out.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus