Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

It's official: Primitive life could have lived on ancient Mars, NASA says.

A sample of Mars drilled from a rock by NASA's Curiosity rover and then studied by onboard instruments "shows ancient Mars could have supported living microbes," NASA officials announced today (March 12) in a statement and press conference.

The discovery comes just seven months after the Curiosity rover landed on Mars to spend at least two years determining if the planet could have ever supported primitive life.

"A fundamental question for this mission is whether Mars could have supported a habitable environment," said Michael Meyer, lead scientist for NASA's Mars Exploration Program at the agency's headquarters in Washington. "From what we know now, the answer is yes." [The Search for Life on Mars (Photo Timeline)]

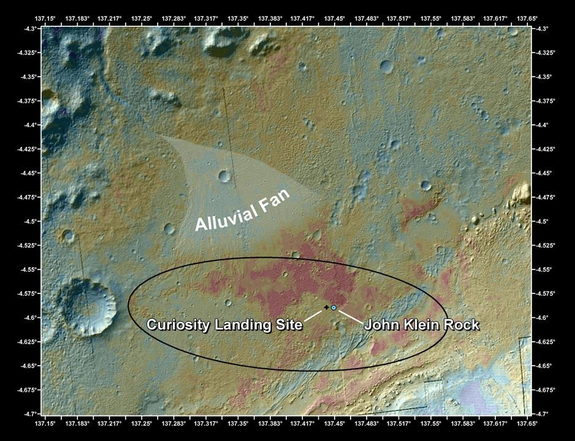

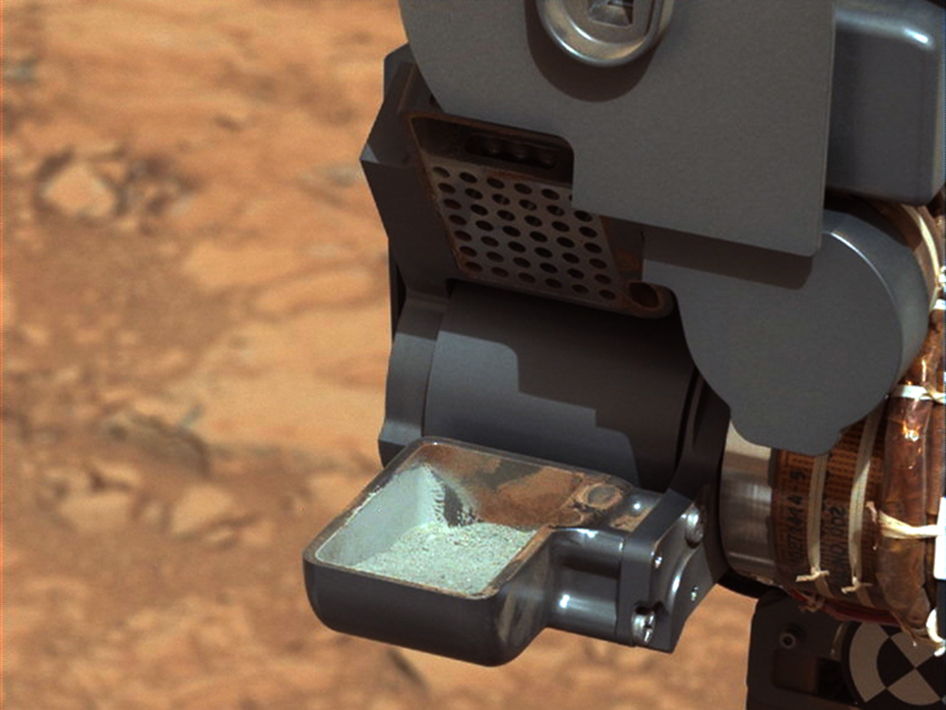

Curiosity drilled into a rock on Feb. 8, boring 2.5 inches (6.4 centimeters) into an outcrop called John Klein using its arm-mounted hammering drill, going deeper than any robot had ever dug into the Red Planet before. Two weeks later, the rover transferred the resulting gray powder samples into two onboard instruments called Chemistry and Mineralogy (CheMin) and Sample Analysis at Mars, or SAM.

CheMin and SAM identified some of the key chemical ingredients for life in this powder, including sulfur, nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen, phosphorus and carbon. The fine-grained John Klein rock also contains clay minerals, suggesting a long-ago aqueous environment that was salty and neutral, researchers said — that is to say, a place that likely was habitable.

Analysis of the samples was complicated by a computer glitch that's still affecting Curiosity today.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In late February, Curiosity's handlers determined that a glitch had affected the flash memory on the rover's main, or A-side, computer system. So they swapped the rover over to its backup (B-side) computer, which caused the robot to go into a protective "safe mode" on Feb. 28.

Curiosity emerged from this safe mode on March 2, only to be put on standby briefly once again a few days later to wait out a Mars-bound solar eruption. Full science operations have yet to resume, but Curiosity's B-side computer is working well as engineers continue to work through the mysterious problem with the A-side, team members said.

"These tests have provided us with a great deal of information about the rover's A-side memory," Jim Erickson, Curiosity deputy project manager at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., said in a statement. "We have been able to store new data in many of the memory locations previously affected and believe more runs will demonstrate more memory is available."

Engineers plan to upload two software patches later this week, then reassess when full mission operations can resume, officials said.

Curiosity landed inside Mars' huge Gale Crater onAug. 5, kicking off a two-year prime surface mission to determine if the Red Planet has ever been able to support microbial life. CheMin and SAM are two of the 10 instruments it carries to aid this quest.

While Curiosity has already made a number of interesting discoveries near its landing site — including an ancient streambed where water likely flowed continuously for thousands of years — its main destination is a set of interesting deposits at the base of Mount Sharp, which rises 3 miles (5 kilometers) from Gale's Center.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus