International Shark Trade to Be Regulated

This story was updated on Tuesday, March 12, at 12:00 p.m. E.T.

Conservationists voted Monday (March 11) to regulate the international trade of five species of sharks that are threatened by overfishing and targeted for their valuable fins.

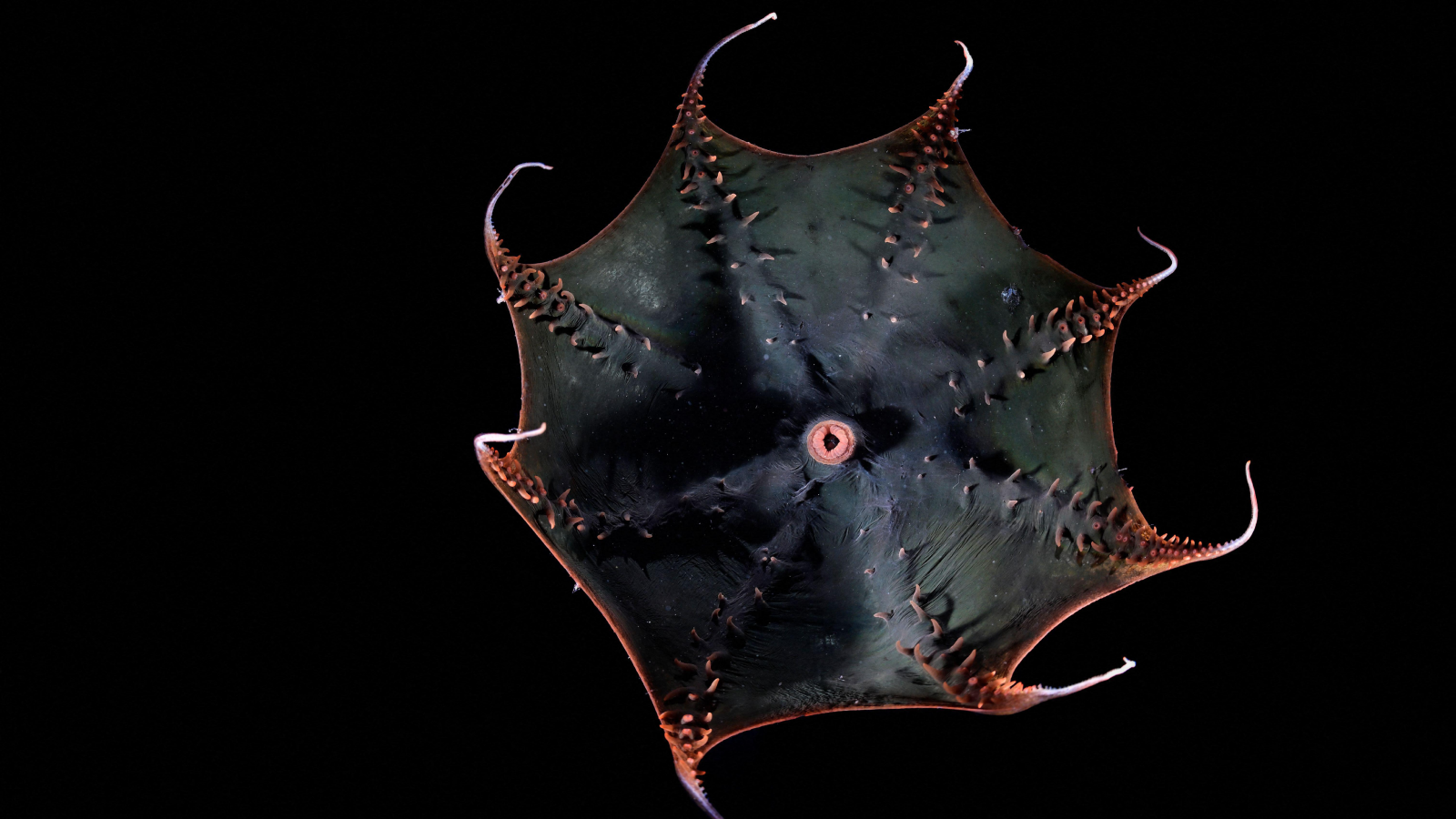

Oceanic whitetip sharks, porbeagle sharks, scalloped hammerheads, great hammerheads and smooth hammerheads — as well as two species of manta rays — are set to get new protections after this week's votes at the meeting of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) in Bangkok.

If the proposals are upheld at a plenary session later this week, all seven animals will be listed under Appendix II of the CITES Treaty, which includes species that may become threatened with extinction if they are traded unsustainably. So far, basking sharks and great white sharks are the only species of elasmobranch (a family that includes sharks, rays and skates) listed on Appendix II.

Sharks are apex predators that help balance ecosystems in the world's oceans, and they have slow growth and reproductive rates, making it difficult for their populations to bounce back from big losses. The votes at CITES were applauded by conservationists and biologists who say overfishing is by far the biggest pressure faced by sharks. [On the Brink: A Gallery of Wild Sharks]

The fish are harvested for their meat, liver oil and cartilage, as well as their fins, which are cut off to be used in shark fin soup, an ancient and prized delicacy in East Asia. According to the World Wildlife Fund, a shark's fin can sell for up to $135/kg in Hong Kong.

"That market has created a lot of demand for shark fins and even spawned a brutal practice in some fishing communities called 'finning,' in which sharks have their fins cut off (the most valuable part) and are then thrown back alive but finless, where they most certainly die," Alistair Dove, a marine scientist at the Georgia Aquarium, told LiveScience in an email. "Manta rays are facing a similar challenge, except that in those species it is the gill rakers that have developed a market for use in Chinese traditional medicine, leading to unsustainable harvest of those peaceful and graceful plankton feeders."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

David Shiffman, a shark biologist, told LiveScience that for the species what will be covered under the new CITES listing, "a lot of the trade is largely unregulated and it's led to massive population declines, particularly for hammerheads and oceanic whitetips."

Though the decline of shark populations has been documented, scientists don't have great data on how bad the problem is since unregulated and illegal catches often go unreported. A study out earlier this month estimated that about 100 million sharks are killed each year, but researchers said the real number of annual shark deaths could fall in a rather large range, between 63 million and 273 million. Shiffman was hopeful that more regulation will give scientists a better idea of the numbers.

"This will lead to additional data about the harvest of these species, which will allow us to make more informed management decisions in the future," Shiffman said. "More data is always better for science."

To help drum up support for shark-protecting proposals, the U.S. delegation to CITES says it worked with other countries, including Brazil, Colombia, the European Union, Costa Rica, Honduras, Ecuador, Mexico and Egypt.

"We are extremely pleased that CITES member nations have given greater protections to these commercially exploited marine species," Bryan Arroyo, head of the U.S. delegation, said in a statement. "Through the cooperation of the global community, we can begin addressing the threats posed by unsustainable global trade in shark fins and other parts and products of shark and ray species."

The CITES Treaty is signed by 178 countries, and a meeting is held every two to three years to review and negotiate changes to the international trade of species covered by the agreement. Whereas sharks fared well during this year's meeting, another highly anticipated proposal to ban the trade of polar bear hides and parts was shot down.

Follow LiveScience us on Twitter @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.