Plugged In: Shark Fetuses Detect Predators' Electric Fields

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Baby sharks still developing within leathery egg cases can sense the electric fields of predators and freeze in place to avoid detection, researchers say.

These findings could help in developing more effective shark repellents, scientists said.

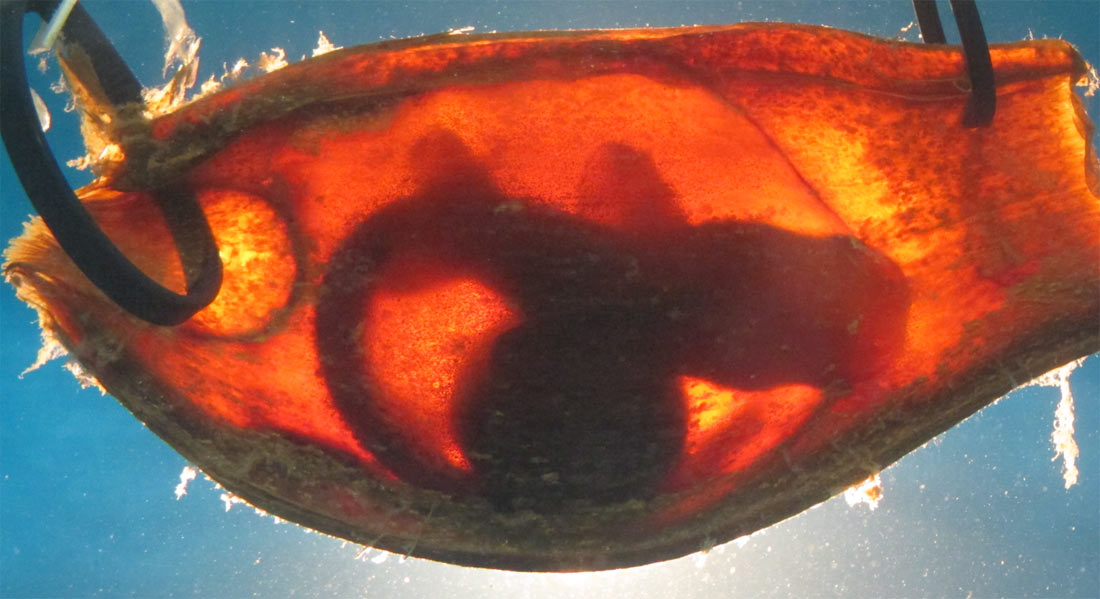

A number of species of sharks deposit embryos in rectangular capsules once whimsically called mermaid's purses or devil's purses. These egg cases often possess long tendrils at each corner that help anchor them to surfaces.

The shark parents of these embryos use highly sensitive receptors known as the ampullae of Lorenzini to detect the electric fields generated by the muscle contractions of potential prey. Now scientists find their embryos can similarly detect the electric fields of potential predators to help them escape being eaten.

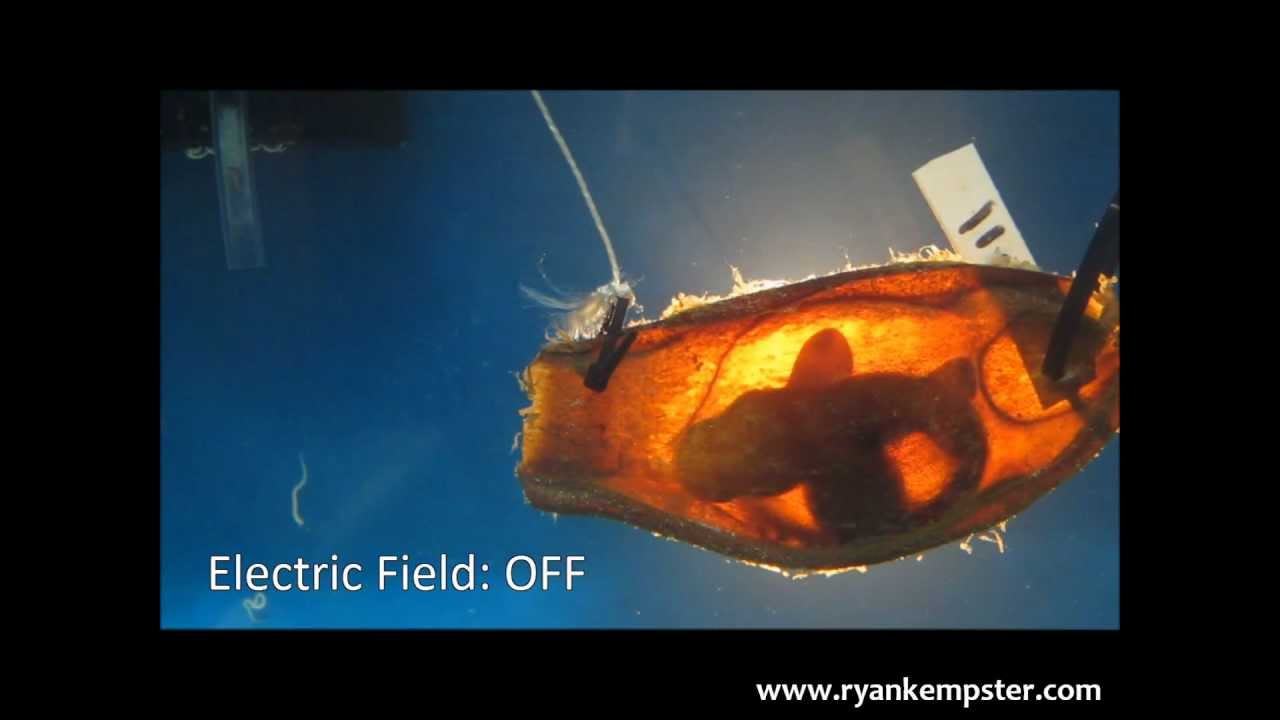

The researchers focused on the brown-banded bamboo shark (Chiloscyllium punctatum). Their embryos spend up to five months inside egg cases, where they are vulnerable to attack from fish, marine mammals and even large mollusks.

The investigators discovered that even within their egg cases, the embryos could apparently detect electric fields in the lab created to mimic those of predators such as fish. Video recordings showed the developing shark babies responded by ceasing all movements of their gills and keeping their bodies perfectly still. [See Video & Images of Developing Bamboo Sharks]

Learning more about such behaviors may help researchers develop effective shark repellents, ones that generate electric fields that sharks keep away from, said researcher Ryan Kempster, a marine neuroecologist at the University of Western Australia.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"There are a variety of commercially available, nonlethal electric shark repellents, but the scientific data supporting their effectiveness is limited," Kempster told LiveScience. This line of research helps analyze what reactions different species of sharks have toward predatorlike electric fields and how these responses might or might not change over time.

Although shark attacks attract attention worldwide, humans are far more dangerous to sharks than sharks are to humans.

"As founder of the shark conservation group Support Our Sharks, a driving force behind my work is not only in producing a repellent to protect ocean users from potential attack, but also to protect sharks from being killed," Kempster said.

"In an attempt to make the ocean a safer place, governments in western Australia, Hawaii and France's Reunion Island have previously implemented pre-emptive killing of sharks. Given the crucial role that sharks play in ocean ecosystems, I believe it is much more appropriate to take advantage of nonlethal shark-control measures instead."

Shark numbers are declining rapidly worldwide, mostly as a result of accidental catches in fishing nets. An electric shark repellant may also help reduce such catches "by keeping sharks away from fishing gear, to decrease the number of sharks unnecessarily killed each year," Kempster said.

The scientists detailed their findings online Jan. 9 in the journal PLOS ONE.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus