Hormones Explain Why Girls Like Dolls & Boys Like Trucks

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

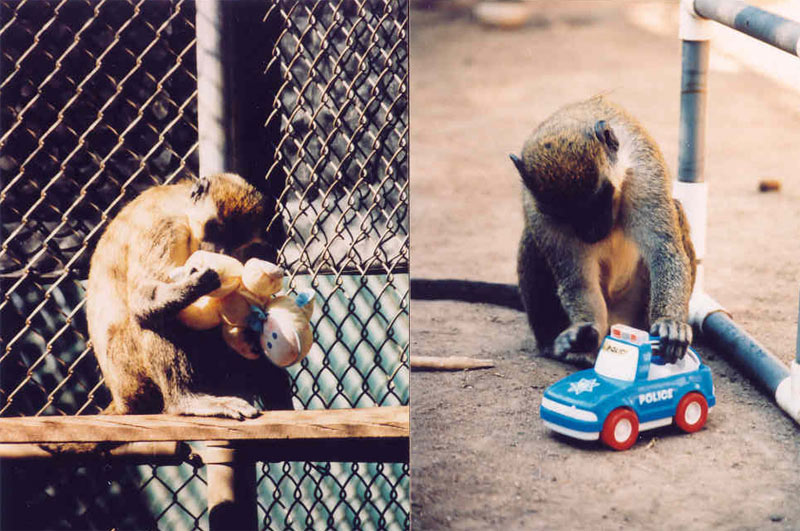

When offered the choice of playing with either a doll or a toy truck, girls will typically pick the doll and boys will opt for the truck. This isn't just because society encourages girls to be nurturing and boys to be active, as people once thought. In experiments, male adolescent monkeys also prefer to play with wheeled vehicles while the females prefer dolls — and their societies say nothing on the matter.

The monkey research, conducted with two different species in 2002 and 2008, strongly suggested a biological explanation for children's toy preferences. In recent years, the question has become: How and why does biology make males (be they monkey or human) prefer trucks, and females, dolls?

New and ongoing research suggests babies' exposure to hormones while they are in the womb causes their toy preferences to emerge soon after birth. As for why evolution made this so, questions remain, but the toys may help boys and girls develop the skills they once needed to fulfill their ancient gender roles.

First, in 2009, Gerianne Alexander, professor of psychology at Texas A&M University, and her colleagues found that 3- and 4-month-old boys' testosterone levels correlated with how much more time they spent looking at male-typical toys such as trucks and ballscompared with female-typical toys such as dolls, as measured by an eye tracker. Their level of exposure to the hormone androgen during gestation (which can be estimated by their digit ratio, or the relative lengths of their index and ring fingers) also correlated with their visual interest in male-typical toys.

"Specifically, boys with more male-typical digit ratios showed greater visual interest in a ball compared to a doll," Alexander told Life's Little Mysteries.

Kim Wallen, a psychologist at Emory University who has studied the gender-specific toy preferences of young rhesus monkeys, said, "The striking thing about the looking data shows that the attraction to these objects occurs very early in life, before it's likely to have been socialized."

Further buttressing the idea that toy preferences are caused by hormones, last year, a group of British researchers found that girls with a condition called congenital adrenal hyperplasia, who experienced abnormally high levels of the male sex hormone androgen while in the womb, prefer to play with male-typical toys. [Why Is Pink for Girls and Blue for Boys?]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But why would male sex hormones make people favor wheeled vehicles and balls? A common explanation holds that these toys facilitate more vigorous activity, which boys are evolutionarily programmed to seek out. But the 2009 study indicated that their affinity for balls and trucks predates the stage when children actually start playing with toys. At just 3 months old, the newborn boys already fixed their eyes on the toys associated with their gender.

"Given that these babies lack physical abilities that would allow them to 'play' with these toys as do older children, our finding suggests that males preference for male-typical toys are not determined by the activities supported by the toys (i.e., movement, rough play)," Alexander said.

Wallen approaches the data more cautiously. "It's hard to interpret what the looking data mean because we don't know why people are attracted to specific things. Clearly children recognize that certain objects in their environment are appropriate for certain activities. They could be looking at a certain toy because it facilitates an activity they like," he said.

The debate over why boys prefer toy vehicles and balls continues. In a new study, Alexander and her colleagues investigated whether 19-month-olds move around when playing with trucks and balls more than they do when playing with dolls. According to the study, they don't. Toddlers with higher levels of testosterone are more active than toddlers with lower levels of the sex hormone, but the active toddlers moved around just as much when holding a toy truck, ball or doll. "We find no evidence to support the widely held belief that boys prefer toys that support higher levels of activity," she wrote in an email. A paper detailing the work has been accepted for publication in the journal Hormones and Behavior.

If it isn't vigorous activity they're after, it could be that boys simply find balls and wheeled vehicles more interesting, while human figures appeal more to girls. As for why evolution would program these toy preferences, the researchers have a few ideas. According to Alexander, one possibility is that girls have evolved to perceive social stimuli, such as people, as very important, while the perceived worth of social stimuli (and thus, dolls that look like people) is weaker in boys. [The Smarter Sex? Women's Average IQ Overtakes Men's]

Boys, meanwhile, tend to develop superior spatial navigation abilities. "Multiple studies in humans and primates shows there is a substantial male advantage in mental rotation, which is taking an object and rotating it in the mind," Wallen said. "It could be that manipulating objects like balls and wheels in space is one way this mental rotation gets more fully developed."

This is purely speculative, Wallen said, but boys' superior spatial abilities have been tied to their traditional role as hunters. "The general theory is that well-developed skills in mental rotation allowed long distance navigation: using an egocentric system where essentially you navigate using your perception of your location in 3D space," he said. "This might have facilitated long distance hunting parties."

Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover or Life's Little Mysteries @llmysteries. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus