Fossil Fish Eye Surprise: Small Structures Reveal Pigment

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

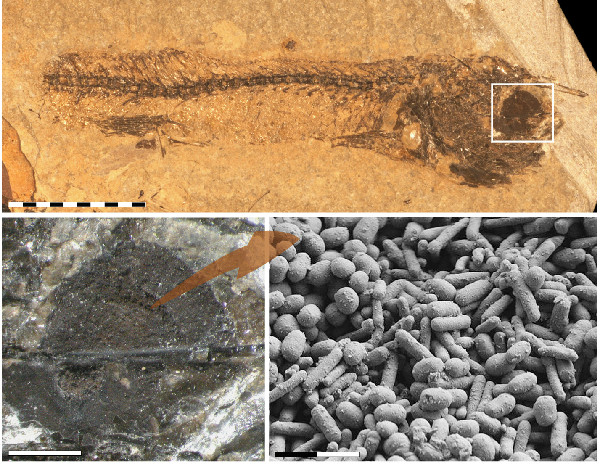

Tiny pebblelike structures found in a 54-million-year-old fossilized fish eye contain the natural pigment, melanin, a study reveals.

Similar structures show up regularly on fossilized feathers, hair and eyes, and in recent years, some scientists have suspected they contained melanin, a dark pigment found in the hair, skin and eyes of humans and animals.

This study, the first thorough chemical analysis of these microscopic structures, opens the door to better understanding the appearance and behavior of long-dead animals, said study researcher Johan Lindgren of Lund University in Sweden.

The presence of melanin alone does not reveal the color an animal displayed since other factors, such as other microscopic features, can also determine color. However, melanin is evidence of dark areas, such as bands on feathers, and the shapes of the melanosomes may correspond to some basic hues, such as gray, black or brown, according to Lindgren.

The presence of dark patches can provide evidence of camouflage, social signaling or other clues to the animal's behavior, he told LiveScience.

The tiny structures Lindgren and colleagues studied came from the fossilized retina, at the back of the eye, belonging to a bony fish found in Denmark. This is a first step, he said.

"Now, hopefully, we will be able to do so in many other species, and be able to distinguish between different kinds of melanin and other pigments as well," he said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scientists have known about these tiny structures for a long time, but they believed them to be the remains of bacteria that had colonized an animal's body after its death.

In 2008, a group of researchers led by Jakob Vinther, now a postdoctoral student at the University of Texas at Austin, concluded that tiny, organic structures like these, found in fossilized features, were actually preserved cellular structures that contain melanin, called melanosomes.

The most recent study adds to evidence that these tiny structures were not left by bacteria, but came from the now-fossilized animals' bodies, Vinther told LiveScience in an email.

"It clearly shows convincing evidence that the melanosomes we have been working on for the last four years are composed of melanin as we have argued earlier on," he wrote.

Lindgren and colleagues used a variety of techniques to analyze the composition of the rounded, microscopic structures. They then compared the results with those of modern melanin, films created by bacteria and other compounds that common in sediments and have a molecular structure similar to melanin.

Their results from the fossil fish eye were indistinguishable from those of modern melanin, indicating that the original chemistry of the fish's eye had been preserved for 54 million years, he said. [Image Gallery: Freaky Fish]

While bacteria can produce melanin, the dark structures in the retina at the back of the fossilized fish eye are located right where one would expect to find pigment in a living animal, making this the more likely explanation, he said.

The study is published in the May 8 issue of the journal Nature Communications.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus