Leonardo da Vinci: Hollywood's Ultimate Renaissance Man

Inventor Leonardo da Vinci gets to play action hero in two upcoming Hollywood films where he fights supernatural forces and saves Europe from returning to the Dark Ages. It's somehow fitting for the ultimate Renaissance man who not only created famous visions of war machines and human anatomy, but also possessed a heroic combination of brains, good looks and strong muscles.

The painting of the "Mona Lisa" and the "Vitruvian Man" sketch came from the mind of a genius who was also considered a handsome and charming man by his Renaissance peers. One account referred to the inventor having beautiful curly hair that came down to the middle of his chest. Italian contemporary Giorgio Vasari described da Vinci as having the strength to "bend the clapper of a knocker or a horseshoe as if they had been of lead" — surely music to the ears of Hollywood casting directors.

Perhaps the best power da Vinci had was his keen sense of sight and the imaginative vision, said Toby Lester, author of "Da Vinci's Ghost" (Free Press, 2012). The inventor's notebooks contained astonishing 3D drawings of everything from human bodies to wild engineering designs.

"He had an uncannily weird ability to see things in ways that other people hadn't seen before then," Lester explained. "A lot of his anatomical drawings were drawn in ways we could only see with MRIs and CAT scans today."

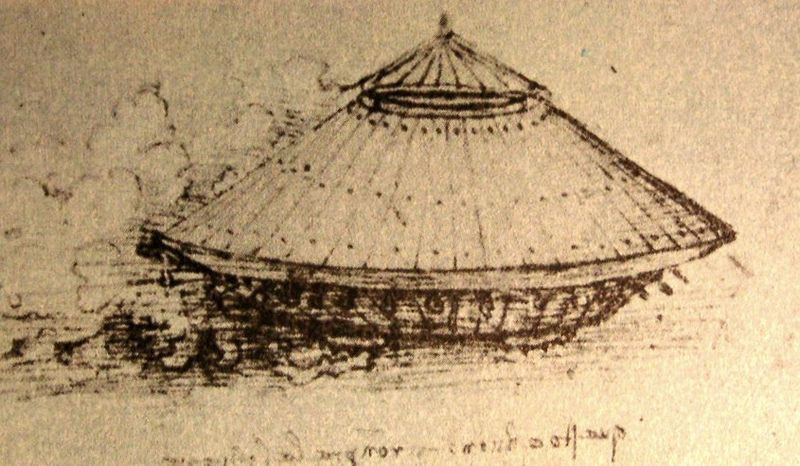

Many of da Vinci's sketches of primitive tanks and flying machines have already come to life in the popular "Assassin's Creed" video games, and will likely receive the Hollywood treatment as his superhero gadgets in the upcoming films.

But da Vinci was not the only person drawing inventive siege engines or semiautomatic weapons in 15th-century Italy, Lester said. Some of his war machine sketches were "riffing on the ideas of other people," and others were "utterly impractical."

Still, Lester credits da Vinci for envisioning many scientific advances and technologies ahead of his time.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"What's weird about Leonardo is that he anticipated all sorts of revolutionary breakthroughs in science and medicine, and yet in fact, if he'd never have existed, most of those things would have happened anyway," Lester told InnovationNewsDaily.

Da Vinci's inquisitive mind led him to fill his notebook with drawings and the repeated Italian phrase "dimmi, dimmi," meaning "tell me, tell me" — a personal tic that da Vinci may have used to get his writing ink flowing. Such roaming interest in all fields of science and art manifested itself in a distracted, if brilliant, inventor who tended to leave art works unfinished and patrons angry.

That need not qualify da Vinci from action hero casting. After all, what treasure-hunting adventurer, secretive spy or superhero doesn't have his or her flaws?

"You could cast him as a superheroic procrastinator," Lester said. "If Ritalin had been around, he probably would have been a less memorable guy, but he would have got more stuff done."

This story was provided by InnovationNewDaily, a sister site to Live Science. This is part of an InnovationNewsDaily series about the compelling aspects of various inventors' lives, personalities and inventions and the role they played in Hollywood, pop culture and the progress of society in general. You can follow InnovationNewsDaily Senior Writer Jeremy Hsu on Twitter @ScienceHsu. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.