Waves Break Coral Embryo into Identical Twins

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Ever wanted an identical twin? A clone to do your chores? If you were a coral embryo, you could just break in two and make yourself a body double, new research suggests.

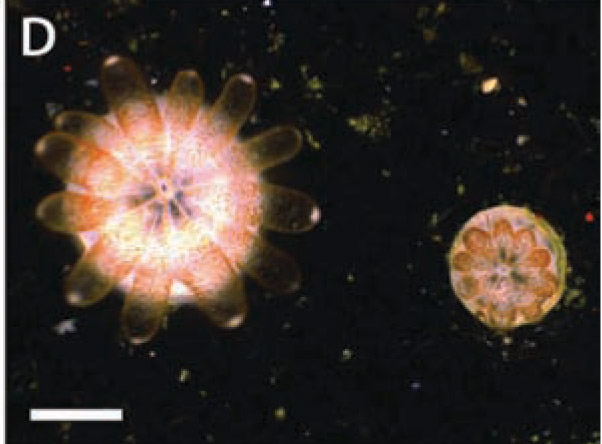

Coral embryos, which are complex marine animals with differentiated cell layers and tissues, are able to reorganize their bodies, even if they've broken in half, to form anew. This means that when even a gentle wave comes along and a coral embryo is damaged, it just ends up turning into two smaller, identical twins.

This ability "helps to explain how coral maximize their chances of finding a suitable habitat in which to settle and survive," study researcher Andrew Heyward, of the Australian Institute of Marine Science, said in a statement. "This is another example of the complexity of these incredible animals and suggests that there may be more to learn about the lives of corals."

Embryonic events

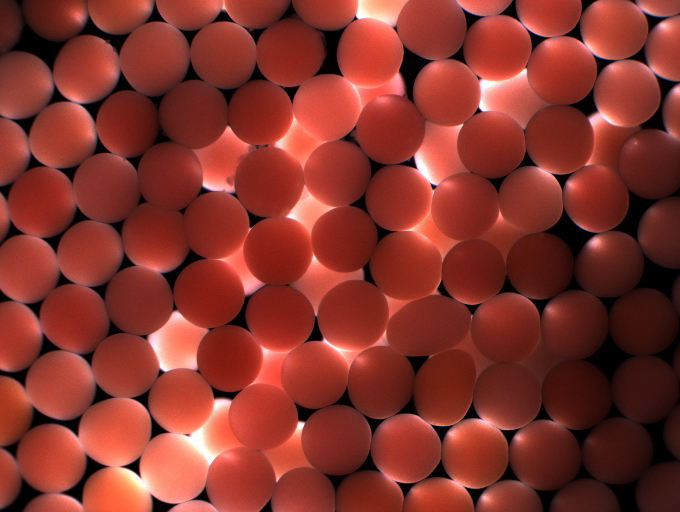

When corals reproduce, they create and release billions of embryos into the oceans around them. These embryos, which form after sperm and egg meet in the water, float to the top, where they are battered by waves and wind as they are carried to new locations, where they grow into juvenile corals.

"As the early-stage embryo develops, it divides into a cluster of cells," Heyward said. "Because this ball of cells lacks a protective outer layer, we wondered whether subjecting them to a little turbulence might cause them [to] break up."

So Heyward and his colleagues simulated in the lab wave conditions on the Great Barrier Reef. They did see the embryos break apart, but what they saw next was unexpected: Rather than dying, the broken parts were able to continue dividing normally to maturity.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Special reproduction

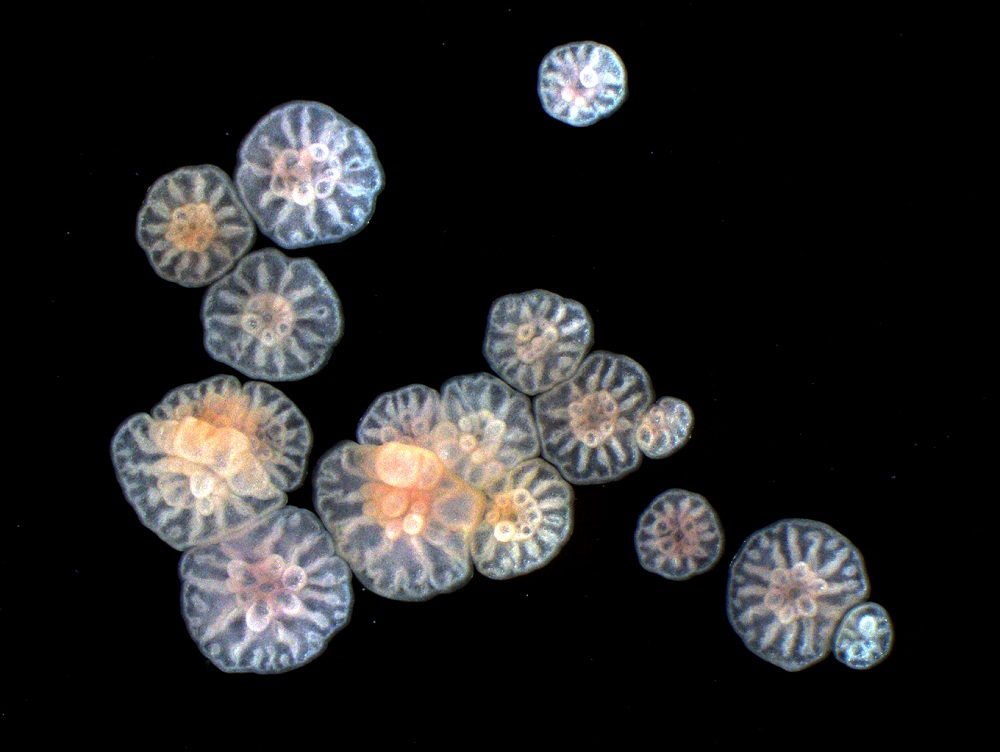

The divided embryos and the resulting juvenile corals were smaller than average, but they were able to settle and grow alongside their full-size siblings in the lab. In the end, being "fragile" is an advantage to the corals — it allows them to create more of themselves, increasing the likelihood that one of the clones will land somewhere hospitable. [Gallery: Peek Inside a Coral Nursery]

"It appears that the lack of protective membrane is no accident," study researcher Andrew Negri, also of the Australian Institute of Marine Science, said in a statement. "Almost half of all these naked embryos fragmented in our experiments, suggesting that this has long been part of the corals' repertoire for maximizing the impact of their reproductive efforts."

What's interesting, on top of the coral embryo making its own identical twin, is that this is a completely new mode of reproduction in the animal kingdom. (Other animals can clone themselves but only if they are already full-grown adults, not embryos.)

This means coral have two ways of reproducing: They can sexually reproduce to create embryos that are genetically different from the parent, and they can also create genetically identical clones from embryos. This reproductive flexibility may help corals survive in the unpredictable ocean environment, the researchers suggest.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus