Lemur-Like Toes Complicate Human Lineage

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A 47-million-year-old primate may have been a fashionista of sorts, as new analysis of the fossil suggests it sported grooming claws.

Besides helping the primate rake through its fur, particularly in hard-to-reach spots, the grooming claw presents a puzzle of sorts for scientists studying the relationship between a group that includes humans, apes and monkeys, and the family that includes lemurs.

That's because the primate is the first extinct North American primate with a toe bone showing features associated with the presence of both nails and a grooming claw.

Traditionally, it's thought that primates with a toe attachment called a grooming claw were more closely related to lemurs, which are primates like us but are considered more primitive and part of a different family than great apes (including humans) and monkeys. In lemurs, the claw is located on the second toe.

So where does this newly examined specimen fit in? It was "either in the process of evolving a nail and becoming more like humans, apes and monkeys, or in the process of evolving a more lemurlike claw," study researcher Doug Boyer, of Brooklyn College of New York, said in a statement.

Puzzling primate

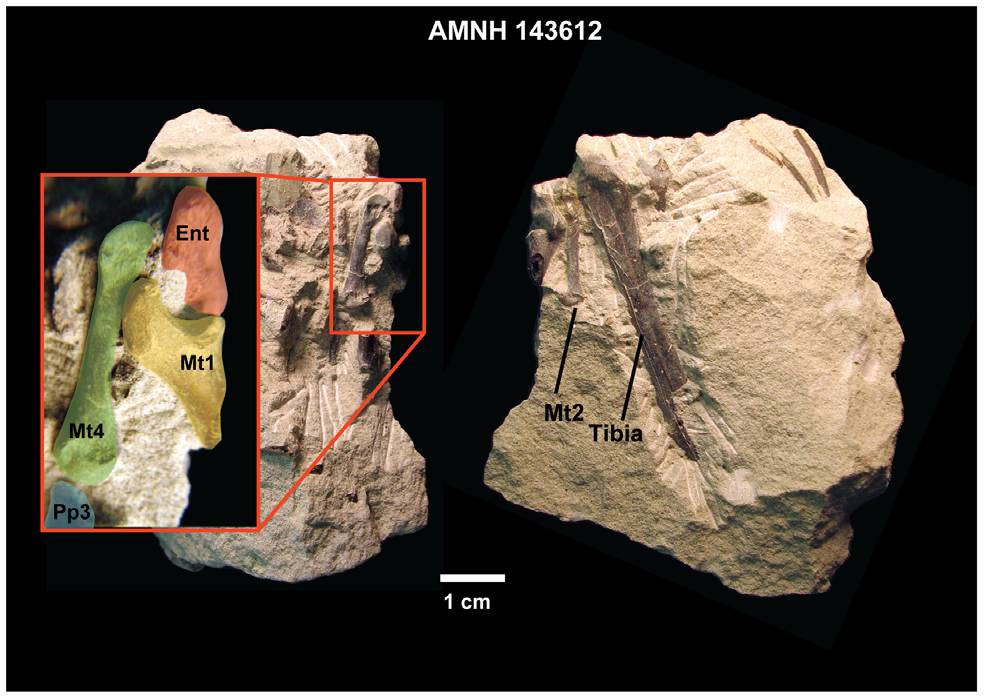

The focus of this study, a specimen unearthed in Bridger Basin in Wyoming years ago, was recovered from a cabinet in the fossil mammal collections at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Now called Notharctus tenebrosus, the primate would have looked similar to its human and monkey cousins of the time, but its bones show the presence of a grooming claw.

The researchers compared the anatomies of an extinct primate species, Darwinius masillae, called Ida, and N. tenebrosus, to other known living and fossil primates. After examining the data, both with and without information about the grooming claw, it appeared both these ancient primates were more closely related to lemurs than to monkeys, apes and humans.

The finding also provides clues as to which feature — humanlike nails or claws — served as the starting point in primate evolution. "I now believe it's more likely that nails were the starting point and grooming claws developed as a functional trait," Boyer said.

Where Ida fits in

Another implication of the finding involves the famous "Ida" specimen, a fossil considered to be a possible human ancestor, partly because it lacked a grooming claw, the researchers said.

The researchers on the new paper think their new find muddies the waters about what is and isn't a member of the monkey-ape lineage.

"It's not clear that lacking a grooming claw means a species is related to anthropoids," study researcher Stephanie Maiolino, of Stony Brook University, said in a statement.

Wighart Von Koenigswald, a researcher from the University of Bonn in Germany — who wasn't involved in the current work, but was involved in the Ida discovery — said in a statement that his more recent research on Ida (D. masillae)and related fossils suggests the Ida likely had a grooming claw as well.

Ida's claw could mean that fossils like N. tenebrosus and D. masillae were on their way to becoming the lemur lineage, and had already separated from the ape-monkey evolutionary line.

The study, which was funded in part by the National Science Foundation and Brooklyn College of the City University of New York, is detailed online in the Jan. 10 issue of the journal PLoS ONE.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus