10 Science Discoveries to Be Thankful for

Amazing advances in science

As you bow your head in gratitude, secretly hoping every aunt and uncle won't chime in with their laundry list of thanks, here's a nod to the most breathtaking — or plain necessary — advances in science.

The discovery of vaccines

They're a lightning rod for controversy these days, but there's no denying: Vaccines save lives. More than 1,000 years ago in China, Africa and Turkey, people inoculated themselves with smallpox pus to prevent the disease; the practice went viral, so to speak, in 1796 after English scientist Edward Jenner figured out that he could use pus from a milder bovine disease called cowpox to inoculate against smallpox. In the ensuing centuries, researchers have developed vaccines for deadly disease like diphtheria, tetanus, typhoid, polio and measles. Today, we even have vaccines like Merck's Gardasil, which protects against the cancer-causing human papillomavirus. The next step is therapeutic vaccines, which are under investigation as a method of boosting the immune system in patients who are already sick with diseases like hepatitis, HIV and cancer.

Learning about what causes illness

During the 1800s, evidence began to mount that diseases weren't caused by foul air or spontaneous generation. Believe it or not, the idea that there might be some sort of contagion causing illness was controversial. This controversy came to a head in 1854, when a cholera outbreak hit the Soho neighborhood of London with deadly fury. In the first three days of the epidemic alone, 127 people in the neighborhood died, according to the University of California, Los Angeles, Department of Epidemiology. Within weeks, the death toll reached 500. But physician John Snow was on the case, interviewing families and searching for a common thread. He found it in a contaminated water pump on the corner of Broad Street. Once the pump handle was removed so that residents could no longer pump the water, the epidemic stopped in its tracks. (It would take several more years for the scientific community to fully accept that diseases are caused by germs.) Today, outbreaks like SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome), avian flu and the H1N1 flu have the potential to go global within hours. Debate may rage about the appropriate level of response to these threats, but we're thankful to have epidemiologists watching our backs.

Watching the brain in action

The skull is a tough nut to crack, which is why we're glad we can now peer inside without reaching for the circular saw. Neuroimaging, or bran scanning, is one of the newer technologies at researchers' and doctors' disposal. Researchers use computed tomography (CT or CAT scans) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to get a good look at soft tissue, including the brain. With the advent of functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI, in the 1990s researchers have been able to watch the brain in action, finding out what areas become more active during various mental tasks. MRIs have been used to reveal everything from brain maturity to the effect of violent video games on teen brains. Brain scans have even been entered as evidence at murder trials.

The magic of microscopes

Even if microscopes weren't integral to the discovery of the cell – the building block of life as we know it – we'd put them on this list for sheer coolness. How else would we watch chromosomes replicate or marvel at the mosaic pattern of a mosquito eye? Without microscopes, a staggering portion of our world would remain invisible. We've moved beyond (though not discarded) the optical microscopes that English scientist Robert Hooke used to discover the cell; these days, scientists can manipulate individual atoms to write words and draw pictures using scanning tunnel and atomic force microscopes. [Nature Under Glass: Gallery of Victorian Microscope Slides]

Understanding ancient life

Our understanding of ancient life on Earth through fossilized remains goes back to the Greek natural historian Xenophanes, who, around 750 B.C., recognized that clam shells encased in rock in a mountainous region resembled clams from the sea. However, the field made little progress for a long period. In the 11th century, the Persian naturalist, Ibn Sina, proposed a theory of petrifying fluids. But it took a few more centuries before fossils and their relationship to past life was understood. Now, thanks to the steady progress of science, we have what we know to be the remnants of undersea life 50 million years ago in the Burgess Shale, Hippo-like mammals basking in the once-toasty warm Arctic, and dinosaur fossils galore. Yes, ancient pudgy mammals – what's not to be thankful for? Pictured above is a fossil that is more than 120 million years old. Scientists Phil Manning and Roy Wogelius of the University of Manchester mapped trace metals in the fossil to reveal the specimen's original pigmentation patterns.

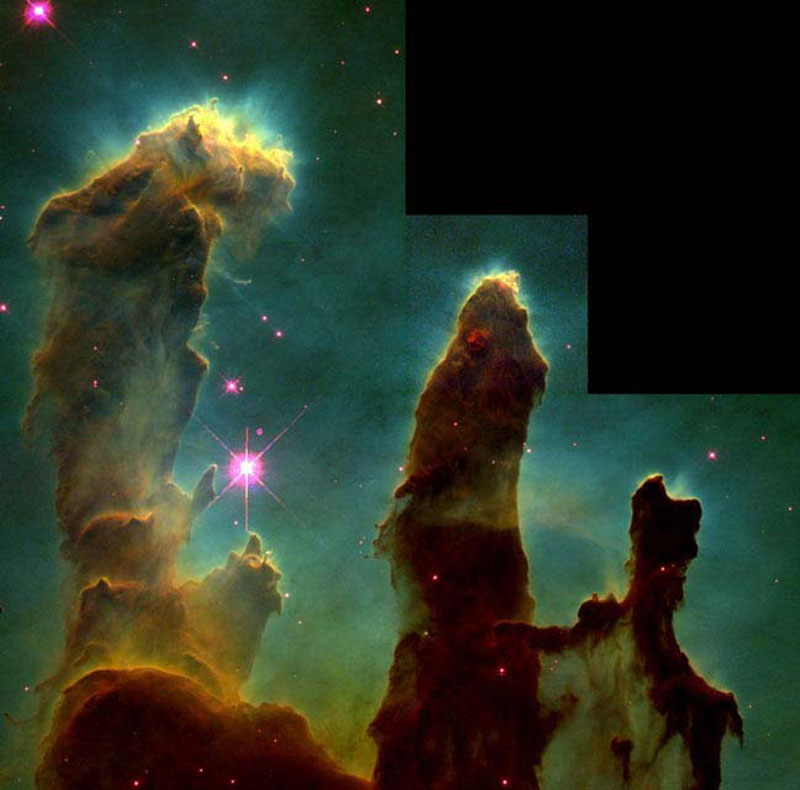

The mighty Hubble

Orbiting 360 miles (579 kilometers) above Earth and weighing as much as two adult elephants, NASA's Hubble Space Telescope is a giant among giants. The telescope has completed about 93,500 trips around the planet, taking three-quarters of a million snapshots and probing 24,000 celestial objects and phenomena. Each day the telescope sends back 3 to 4 gigabytes of data, or enough to fill six CDs. Hubble has arguably changed our view of the universe and our place in it with achievements such as one of the first direct photos of an exoplanet. In its Deep Field Survey, the scope aimed its lens at an "empty patch" of the sky. With a million-second-long exposure, the survey revealed the first galaxies to emerge from the so-called "dark ages," the time shortly after the Big Bang when the first stars reheated the cold, dark universe. Since it's human nature to want to know "where we came from," Hubble gets a big pat on the tube. Pictured above is a classic image of the "pillars of creation" in the Eagle Nebula, taken by the Hubble Space Telescope. [Spectacular Photos from The Revamped Hubble Telescope]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Communication through satellites

The first Soviet satellite to enter Earth orbit may have struck fear in some hearts back in 1957, but the 21st-century world is now addicted to its growing fleet of communication, navigation and remote sensing satellites. GPS satellites help drivers find their way to Black Friday sales, tell smartphone users where to find the nearest Starbucks, and guide the jetliners flying millions of people around the country for Thanksgiving – even if people sometimes rely upon GPS a little too much. [Satellites Gallery: Science from Above] People can also be thankful for satellite radio and satellite TV, even as they look forward to satellite Internet, satellite-guided smart cars, and 4G wireless mobile service for smartphones. Meanwhile, sensing satellites have given us perhaps some of the best views of Earth and its natural rhythms to date. Thanks, orbiting man-made Earth-viewers. The above artist's rendition shows the Cloud-Aerosol Lidar and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observations (Calipso), an environmental weather satellite with remote-sensing technology that continually monitors the Earth's clouds.

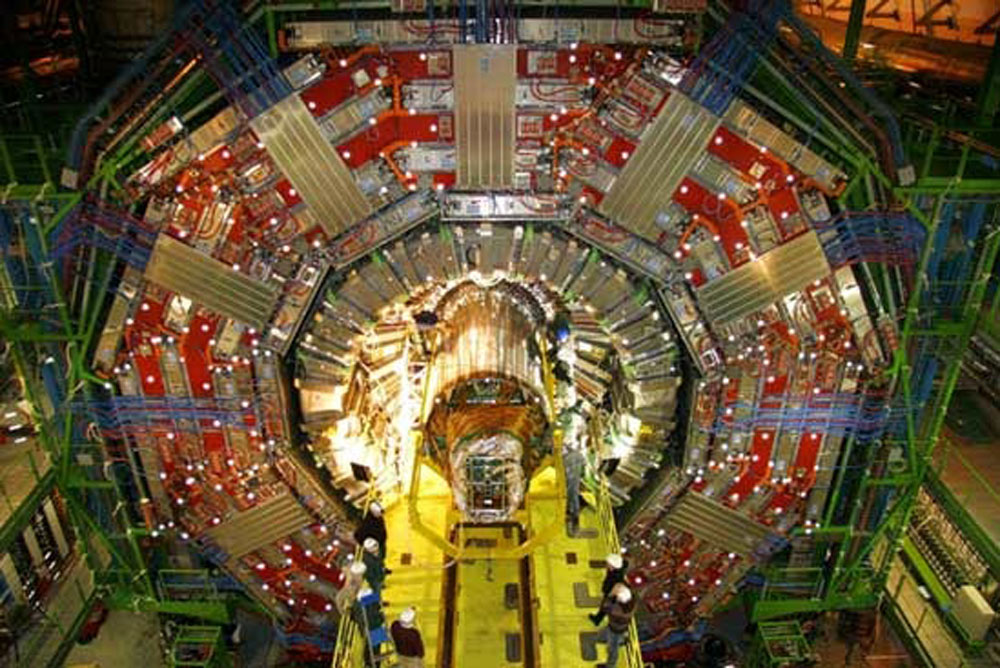

A smashing time: the Large Hadron Collider

Super-high-speed crashes that release enormous amounts of energy and could reveal exotic particles and even recreate conditions in the universe only a trillionth of a second after the Big Bang. That's science any adrenaline junkie could latch onto. The secrets of dark matter, the mysteries of the so-called God particle, and extra dimensions in the universe are just a few of the exotic discoveries scientists are hoping to make with the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), a 17-mile (27-kilometer) circular tunnel running 300 feet (91 meters) underground near Geneva. Recent feat: creating little big bangs. Pictured above is the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS), which is one of the detectors on the Large Hadron Collider and weighs more than 12,000 tons.

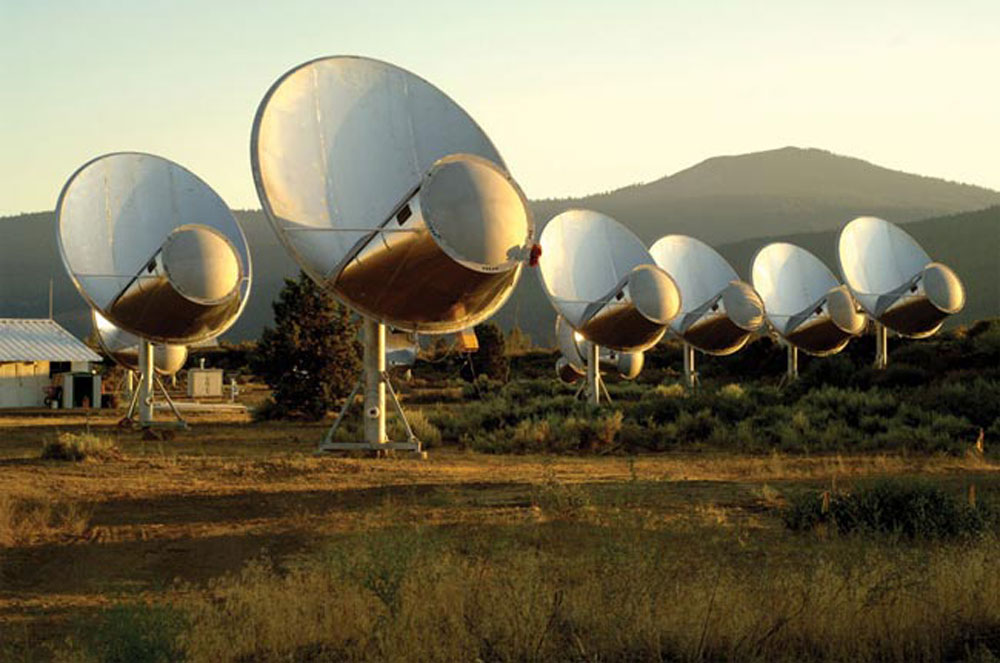

Learning what's out there

The search for extraterrestrial intelligence(SETI) that officially kicked off about 50 years ago has so far failed to turn up signals from little green men. But there's still much to be thankful for about the band of astronomers who listen for radio signals from star systems that could be home to aliens. Such an effort -taps into a sense of trying to understand a universe that extends far beyond humanity and its existence on one rocky planet. It also forces us to consider the meaning behind our existence – are we unique, or has intelligent life stirred elsewhere? Some experts say that we won't find aliens for many centuries, and others predict finding them within 25 years, but the very idea of first contact excites ordinary people enough to want to see encounters at every turn. Just don't tell famed astrophysicist Stephen Hawking about wanting to shake hands with ET. Pictured above is the SETI Institute's Allen Telescope Array at Hat Creek Observatory, located about 290 miles northeast of San Francisco, Calif. The radio telescope has been searching the cosmos for alien signals since 2007.

Sleeping late without guilt

In 1999, Charles Czeisler of Harvard University reported that humans' intrinsic clocks have an average day of 24 hours and 11 minutes. Of course, there is a lot of variation within the population: Some of us, with short-running clocks, rise early and are therefore called larks. Others are comfortable hummingbirds, and the rest are slower-clocked, late-rising owls. The owls among us are thankful for this explanation because it’s proof that wanting to sleep late does not make us lazy. The problem, according to Till Roenneberg, a chronobiologist at Ludwig-Maximilian-University in Munich, Germany, is that in spite of our 24/7 expectations, our society still clings to the agrarian idea of 'the early bird gets the worm.' Here's to catching up on sleep over the long weekend!

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus