Complex Life Emerged from Sea Earlier Than Thought

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

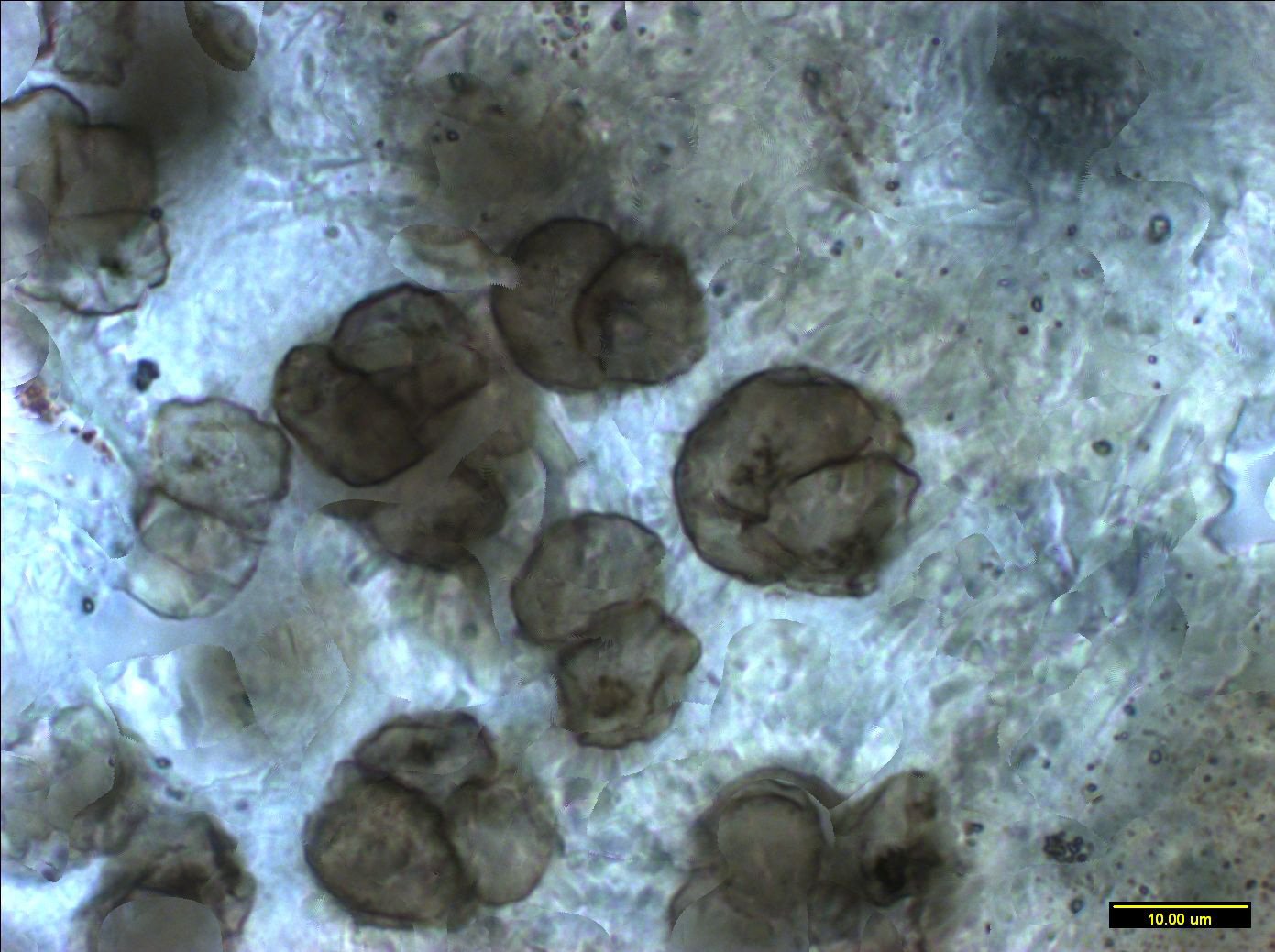

Life on Earth began in the oceans, but new fossils are showing that complex algae-like organisms left these salty seas earlier than thought, about 1 billion years ago, and spent more time evolving on land.

"Most of the time we assume that life originated in the oceans, that the primary divisions and the events of evolution took place there," study researcher Paul Strother, of Boston College, said. "The fact we are finding this complexity and diversity means that the eukaryotes probably had some history of evolution in the freshwater." [Extremophiles: World's Weirdest Life]

For about 2.5 billion years land had been colonized by very simple life, the cyanobacteria. These bacteria don't have specialized compartments within their cells, but they are able to turn sunlight into energy and oxygen, which paved the way for more complex, multicellular life.

Article continues belowEukaryotic emergence

This complex life is the domain of life called the eukaryotes, which gave rise to all the animals (including humans), plants, fungi and single-celled animals like protists. These organisms have a more complex structure than the other domains (bacteria and archaea). They have their genetic code, engines, processing plants and trash bins segregated in separate compartments.

They also likely had sex — reproduced by mixing their genomes together, which most eukaryotes do — and many might have created their own energy from the sun. "In some cases they are going to be displacing things that are already there and in other cases they would be adding a tier to what already existed," Strother told LiveScience.

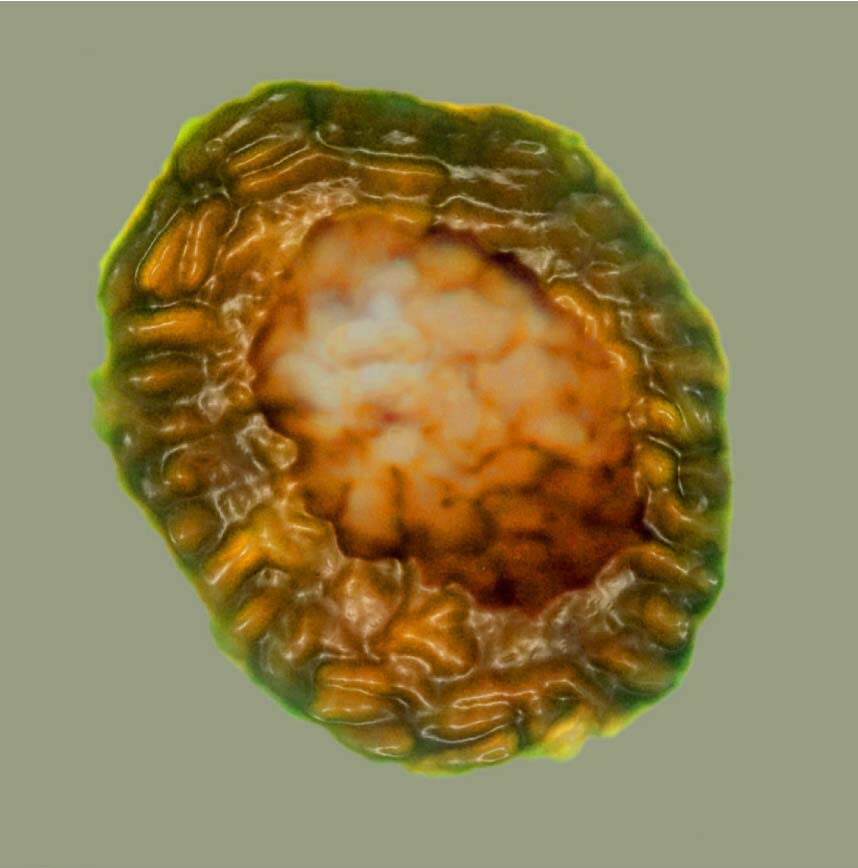

The microfossils show features indicating they had this complex organization within their cells. Some were also aggregates of multiple cells, or had extensions. Many of them were able to synthesize energy from the sun, but it's possible that some were animal-like organisms as well, able to feed on the algae-like organisms.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Freshwater free-for-all

Eukaryotes were already abundant in the seas, but living in freshwater and on land is a much different environment. They had to deal with quickly changing conditions in these habitats. "This also includes environments that are drying up, that are nutrient poor, like lakes, rivers and streams," Strother said. "The range of different environments is much greater on land than it is in the ocean, so theoretically there would be more stimulation for speciation that would be occurring."

These freshwater eukaryotes probably came from their oceanic brethren, but the fossil record for these microorganisms is so spotty, it's hard to tell, Strother told LiveScience. Strother’s team is continuing to sort through samples of microfossils for more examples of the types of complex life that lived at this time.

"We know very little about life in non-marine realms. Strother and colleagues have demonstrated that eukaryote microbes had colonized and flourishedin lacustrine [lake] and other non-marine ecosystems," Shuhai Xiao, a researcher not involved in the study from Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, told LiveScience in an email. "This is not trivial, as biological activities in non-marine ecosystems would have had important impact on global biogeochemical cycles."

The study was published today (April 13) in the journal Nature.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus