Chemical Reaction Darkens Van Gogh Luster

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

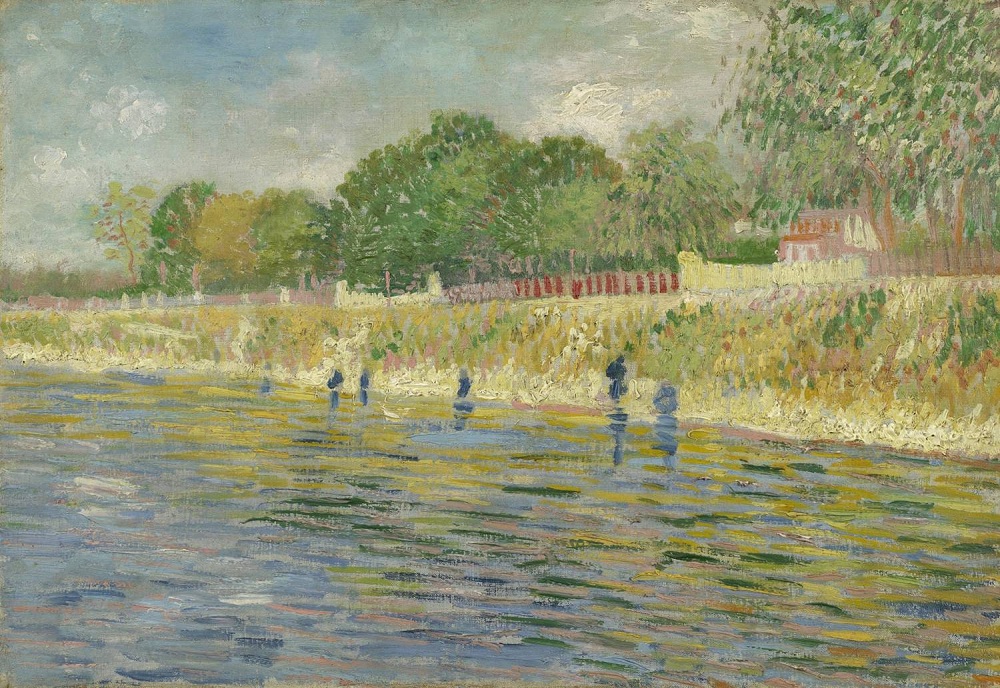

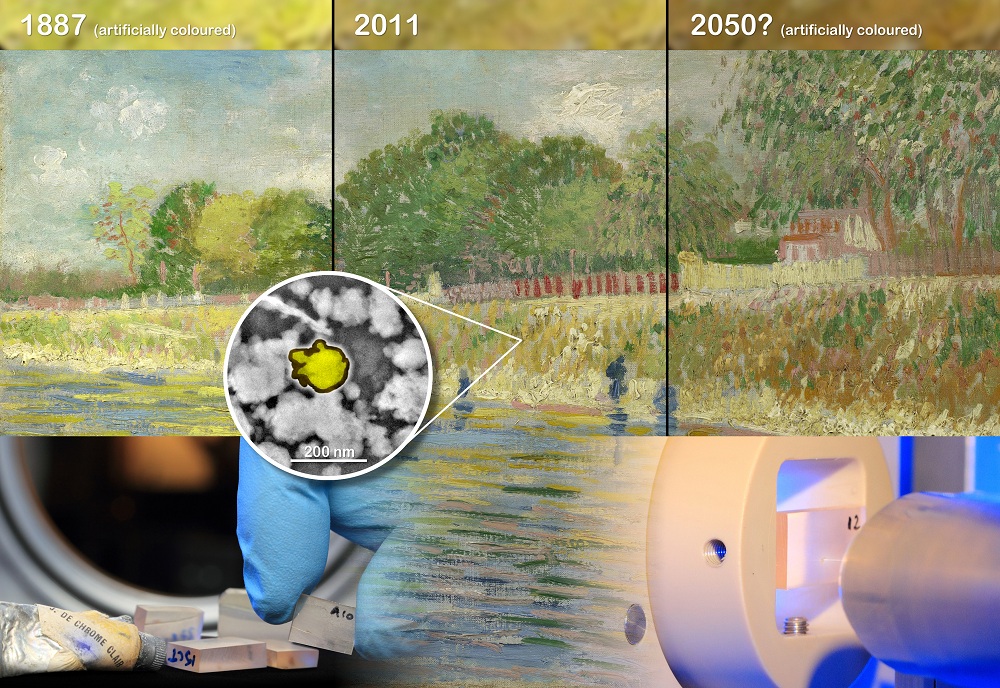

High-tech analysis is showing why impressionist painter Vincent van Gogh's bright yellows are turning to dull browns. The chemical finding could help restorers preserve the 200-year old paintings.

"This type of cutting-edge research is crucial to advance our understanding of how paintings age and should be conserved for future generations," said Ella Hendriks of the Van Gogh Museum Amsterdam, where the two Van Gogh paintings studied are on display.

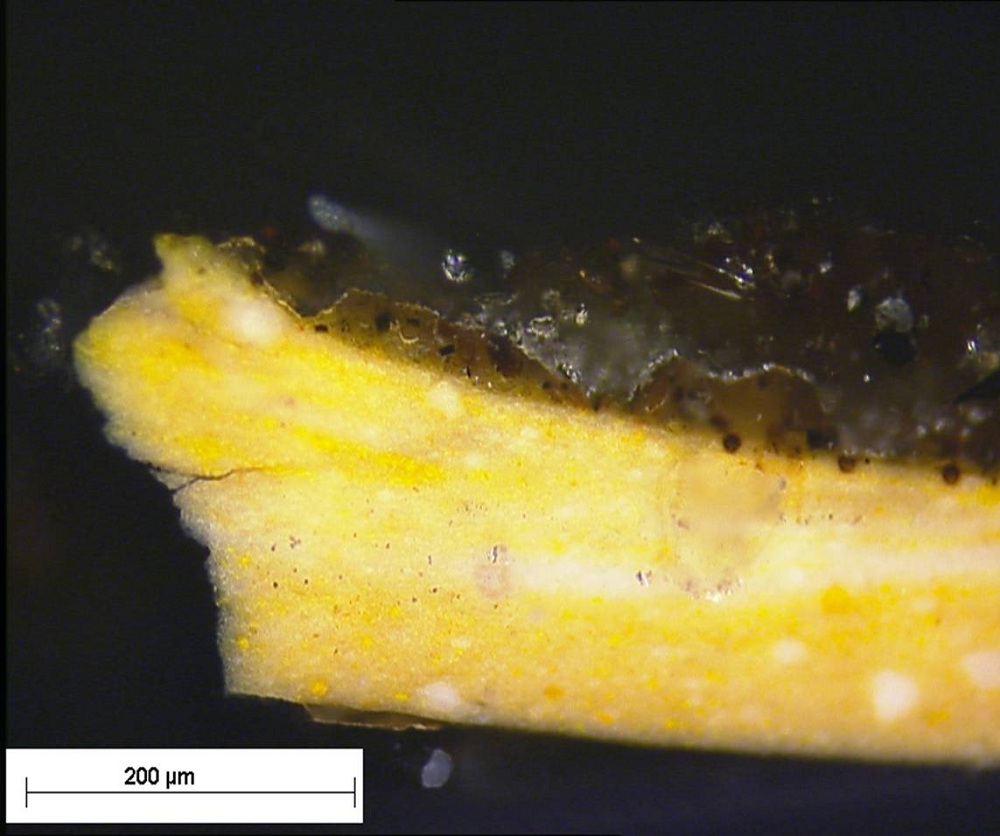

The yellow pigment, used by Van Gogh and his contemporaries, has been undergoing a chemical reaction when exposed to ultraviolet light (including sunlight) that turns the outer layers of the painting brown. The yellow pigment is called chrome yellow, and in a thin layer where the dried paint meets the surface varnish, sunlight penetrates the top layer of the paint. This sunlight triggers a chemical reaction that turns the bright yellow into a dirty brown.

The research team, which included Koen Janssens of Antwerp University in Belgium and Letizia Monico of Perugia University in Italy, discovered that the change was caused when the chromium in the yellow paint was reduced (meaning it gained electrons) from chromium (VI) to chromium (III), changing the color of the pigment.

Not all of the paintings from this period seem to undergo this change in the same time frame. Some haven't been darkened at all. Different painters used different pigments and switched over time, especially since chromium yellow is toxic, so the researchers had to track down some historical paint samples to test.

They found three such tubes of yellow paint and artificially aged the paint by exposing it to 500 hours under a UV lamp. Only one of the paint samples turned brown, one belonging to Flemish artist Rik Wouters. The color change was similar to that seen in the Van Gogh painting, and with X-ray analysis the researchers pinpointed the change to the chromium reduction.

To check that this is what happened to the actual paintings, the researcher took samples from Van Gogh's "View of Arles with Irises" and "Banks of the Seine" and analyzed the pigments. Though the multicolored samples were difficult to analyze, researchers

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

are confident that they likely underwent the same chromium reduction as the artificially aged samples.

"Our next experiments are already in the pipeline. Obviously, we want to understand which conditions favor the reduction of chromium, and whether there is any hope to revert pigments to the original state in paintings where it is already taking place," Janssens said in a statement.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus