The mysterious history of druids, ancient 'mediators between humans and the gods'

Who were the druids, the mysterious religious elite of the ancient Celtic world?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

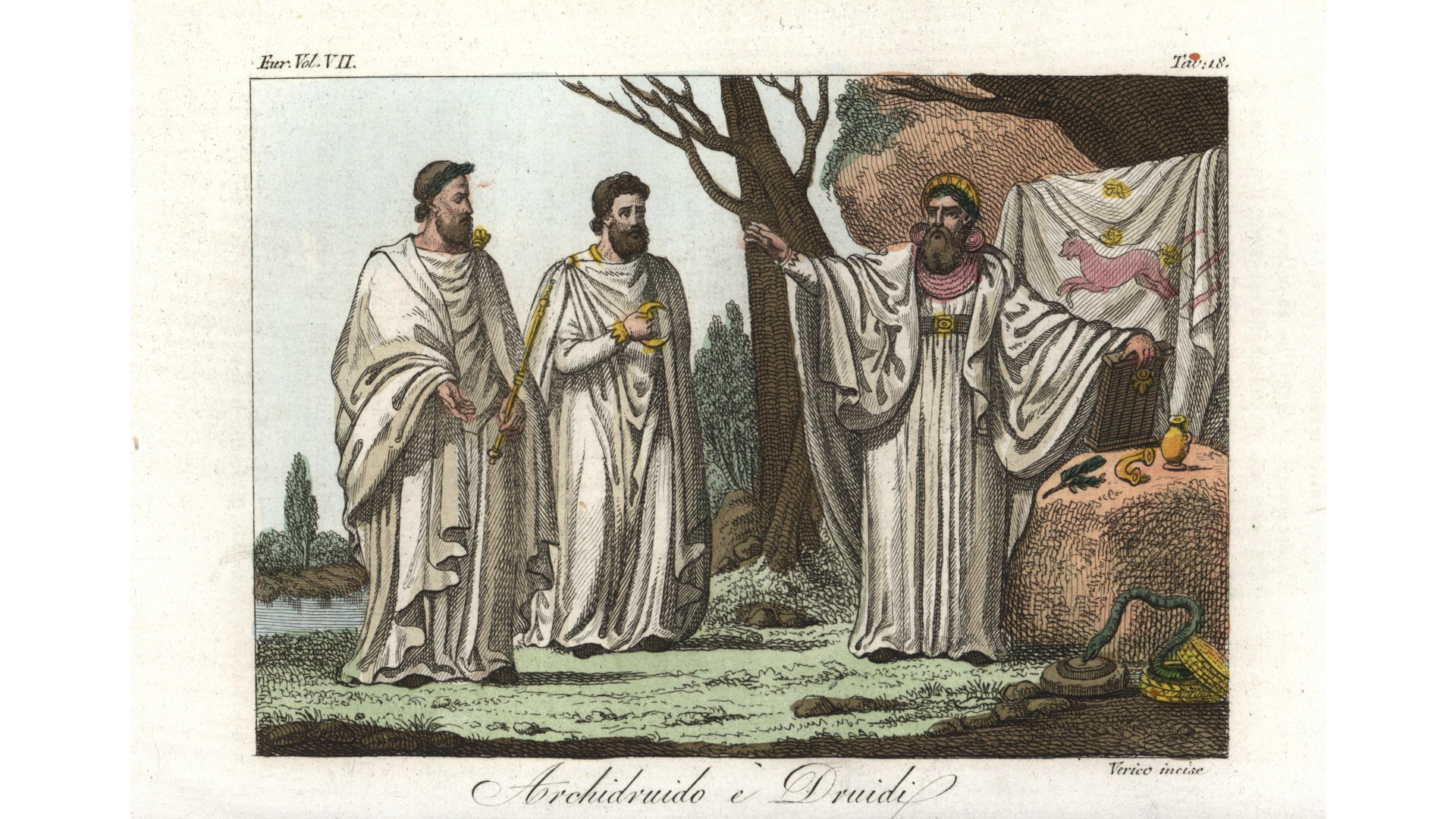

Druids were religious leaders in what is now Britain and France. They were "philosophers, teachers, judges, the repository of communal wisdoms about the natural world and the traditions of the people, and the mediators between humans and the gods," Barry Cunliffe, an emeritus professor of European archaeology at the University of Oxford, wrote in his book "Druids: A Very Short Introduction" (Oxford University Press, 2010).

Almost everything we know about druids is second-hand knowledge; all surviving texts that mention druids were written by non-druids, often Romans. That poses a problem for modern-day historians who are trying to understand who the druids were and how their role changed over time.

Historians aren't quite sure when druidism began. Cunliffe noted that the earliest written reference to the druids dates back about 2,400 years, though druidism likely goes back earlier than that.

Julius Caesar's descriptions of the druids

Julius Caesar, who conquered Gaul in 58 B.C. to 50 B.C. and invaded Britain in 55 B.C. and 54 B.C., is among the principal sources of information about druids.

In a series of books collectively known as "The Gallic Wars," Caesar wrote that the druids "engaged in things sacred, conduct the public and the private sacrifices, and interpret all matters of religion." (Translation by W. A. McDevitte and W. S. Bohn.) In addition to performing religious duties, the druids were often asked to settle disputes.

"If any crime has been perpetrated, if murder has been committed, if there be any dispute about an inheritance, if any about boundaries, [the druids] decide" how to settle it," Caesar wrote. "They decree rewards and punishments."

Groups of druids each had a leader, Caesar noted, and disputes would arise about who should become the leader, which sometimes even led to violence.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Caesar claimed that the druids prohibited their members from writing down their religious beliefs or teachings. He wrote that the druids did not want their "doctrines to be divulged among the mass of the people" and wanted their members to memorize their beliefs and teachings rather than be able to look them up.

Caesar may have actually become friends with a druid. "During his sojourn as military commander in Gaul, he met Diviciacus, ruler of the Aedui — a powerful Burgundian tribe — and he and Caesar became staunch friends and allies, the Roman general commenting that he trusted the Aeduan chief above all the other Gauls," Miranda Aldhouse-Green, an emeritus professor of history, archaeology and religion at Cardiff University in the U.K., wrote in her book "Rethinking the Ancient Druids: An Archaeological Perspective" (University of Wales Press, 2021). While Caesar didn't specifically state that Diviciacus was a druid, the Roman statesman Cicero (who lived at the same time as Caesar) did, Aldhouse-Green wrote.

Druids were active in Britain, Ireland, Gaul (modern-day France) and possibly other regions. The Greek writer Dio Chrysostom, who lived in the first century A.D., compared druids to the magi and the Brahmans of India. The "Celts appointed those whom they call druids, these also being devoted to the prophetic art and to wisdom in general," he wrote. (Translation by H. Lamar Crosby.) Caesar mentioned that Britain was a center of druidism and said that people in Gaul who sought to become druids would sometimes travel there.

Druids and Stonehenge

People today often associate Stonehenge with druidism. However, Stonehenge was constructed mainly between about 5,000 and 4,000 years ago — around 2,000 years before the earliest-known records of druids. So, the question remains of whether druidism existed when Stonehenge was built — and, if so, in what form. Scholars that Live Science reached out to tended to be doubtful that druids were around back then.

"Druids only emerge in the last half of the 1st millennium BC long after Stonehenge was built," Caroline Malone, an emeritus professor at Queen's University Belfast's School of Natural and Built Environment, told Live Science in an email.

There is no link in ancient writings between druids and stone circles. "Classical authors referred to ancient druids worshipping only in wooded groves — there is no mention of any link between druids and stone [monuments] let alone Stonehenge," Mike Parker Pearson, a professor of British later prehistory at University College London, wrote in an article published in 2013 in the journal Archaeology International.

Mistletoe and the moon

Ancient sources provide some tantalizing hints about what druids valued.

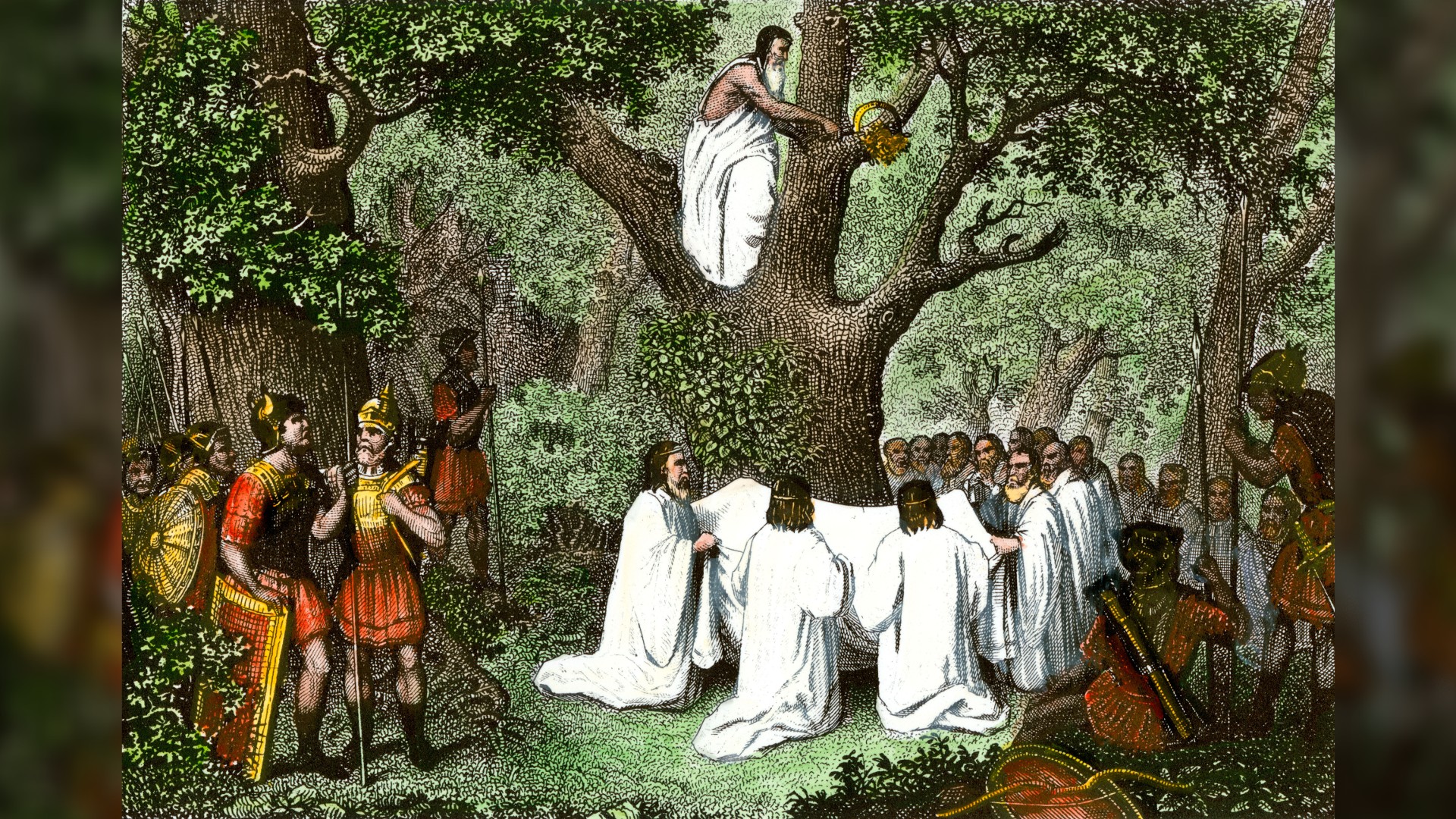

The Roman writer Pliny the Elder (who lived in the first century A.D.) discussed the importance of both mistletoe and the fifth day of the moon to druids. He wrote that mistletoe "is gathered with rites replete with religious awe. This is done more particularly on the fifth day of the moon, the day which is the beginning of their months and years, as also of their ages." (Translation by John Bostock.)

Pliny the Elder also wrote about the importance of animal sacrifice and fertility to the druids. The druids "bring thither two white bulls, the horns of which are bound then for the first time. Clad in a white robe the priest ascends the tree, and cuts the mistletoe with a golden sickle, which is received by others in a white cloak. They then immolate the victims" while offering prayers, he wrote. "It is the belief with them that the mistletoe, taken in drink, will impart [fertility] to all animals that are barren, and that it is an antidote for all poisons."

How widespread was druidism?

Scholars are uncertain how widespread druidism was in the ancient world. It certainly flourished in the British Isles and Gaul. Caesar claimed that druidism originally came from Britain and that those who wished to study it in depth traveled there.

"This institution is supposed to have been devised in Britain, and to have been brought over from it into Gaul; and now those who desire to gain a more accurate knowledge of that system generally proceed [to Britain] for the purpose of studying it," Caesar wrote.

Whether druidism truly originated in Britain, however, is unknown, and it is possible that druids were found much farther afield. Druidism is often associated with a people known as the Celts, and Celt settlements have been found as far east as modern-day Turkey. Additionally, Celtic mercenaries served as far away as Egypt (during the reign of Cleopatra VII) and Judaea.

It's not clear if women could be druids.

Did the druids practice human sacrifice?

The druids may have been involved in human sacrifice. The first-century Greek historian Diodorus Siculus wrote that although the druids were always present during a human sacrifice, it was another group known as the "vates" that carried out the sacrifices.

How widespread human sacrifice was among the cultures the druids served is another mystery. Much of the writing that survives comes from Roman writers, who may have been hostile toward druids and the cultures they were part of.

For instance, in A.D. 60, druids joined a rebellion against the Romans on the island of Mona (modern-day Anglesey) in Wales. Roman historian and politician Cornelius Tacitus reported that after the Romans crushed the rebels, they found widespread evidence of human sacrifice — a claim that may have been exaggerated to cast the druids in a negative light.

"A force was next set over the conquered, and their groves, devoted to inhuman superstitions, were destroyed. They deemed it indeed a duty to cover their altars with the blood of captives and to consult their deities through human entrails," Tacitus wrote. (Translation by Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb.)

Archaeological evidence for druid human sacrifice is controversial. "Lindow man" is the remains of a young man found in a bog in northwestern England who suffered a series of assaults in the mid-first century A.D. and was stripped naked except for a fox-fur armlet, wrote Aldhouse-Green in her book. While it has been speculated that this could be the remains of a druid-related human sacrifice, this is not certain.

The end of druidism

As Christianity spread throughout Europe, druidism gradually faded. Cunliffe noted that druids were still present in Ireland in the eighth century A.D., but in a much-reduced form.

"Druids are now seen to be the makers of love-potions and casters of spells but little else," Cunliffe wrote. "The mood is captured by one 8th-century hymn that asks for God's protection from the spells of women, blacksmiths and druids!"

Druidism likely lasted until around the ninth century. Although druidism faded during the Middle Ages, it has revived in modern times. However, Cunliffe and other scholars have pointed out that there is a gap of almost a millennium between the demise of the ancient druids and the appearance of this revival group.

Additional resources

Learn more about druids in Wales from Amgueddfa Cymru, a group that represents seven museums in Wales. Read an article from Cronkite News that discusses modern-day druids. Read Caesar's "The Gallic Wars," a major ancient source on the druids, via MIT's website.

Originally published on Live Science on May 20, 2014, and updated on Sept. 23, 2022.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus