Are these ancient ruins in Honduras the legendary 'White City'?

Filmmakers documented the expedition to a remote part of the Honduran rainforest in La Mosquitia.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Deep in the northeastern Honduran rainforest, according to local lore, hides an ancient metropolis known as "La Ciudad Blanca," or "The White City." Its name alludes to imposing pillars of white stone that were allegedly glimpsed by Spanish colonizers and, later, Western explorers; the city is rumored to have been dedicated to a monkey god worshipped by a pre-Columbian civilization.

For nearly a century, explorers have searched for the White City in vain. But in 2015, a team of scientists that traveled deep into the jungle in Honduras' La Mosquitia region found ruins that could be those of the fabled city.

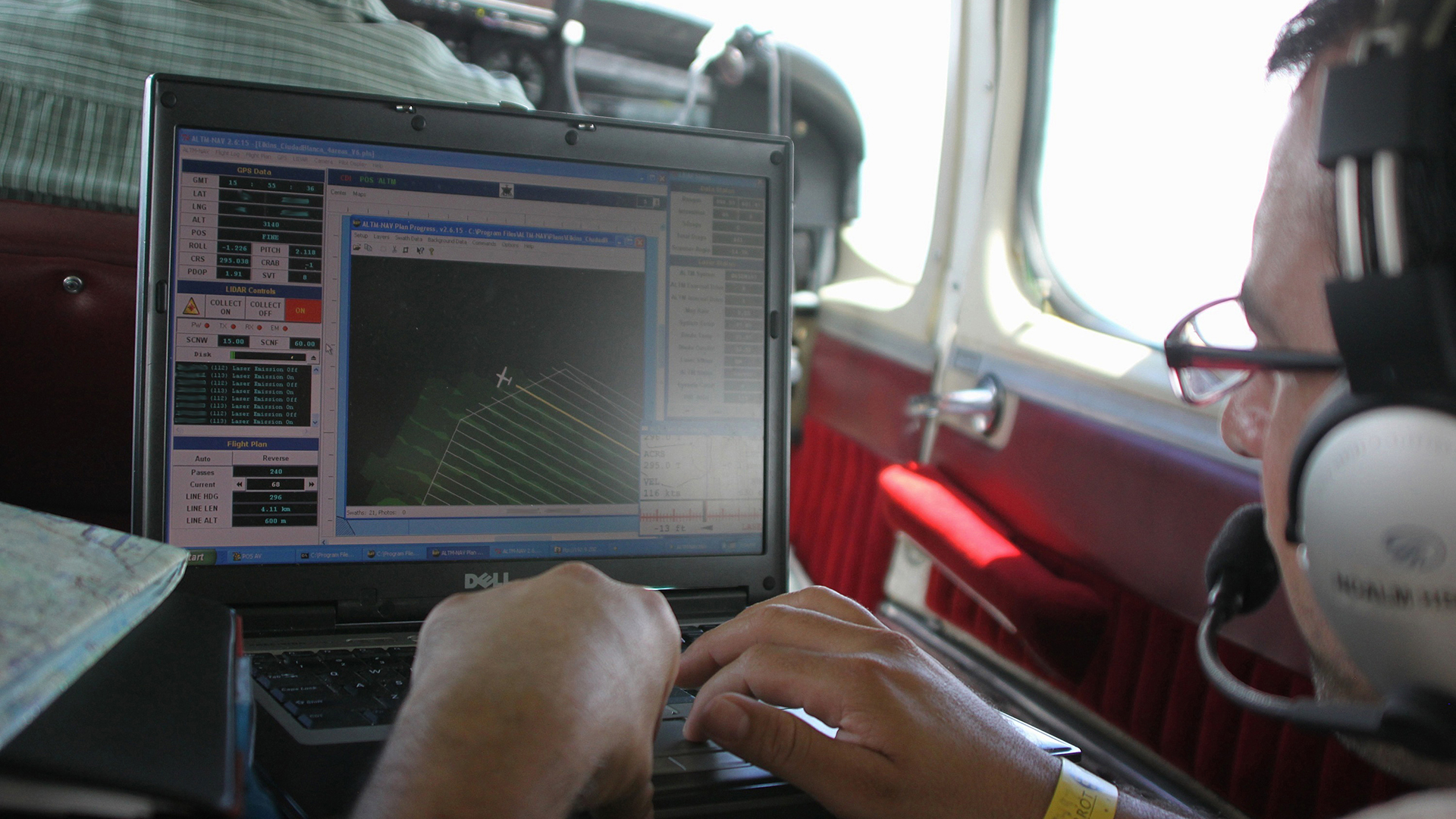

Filmmakers captured the grueling journey in the documentary "Lost City of the Monkey God," which airs Oct. 31 on the Science Channel. Using clues that had been gathered by previous expeditions as well as by ground-surveying satellites and laser scans, they uncovered structures and artifacts that had been swallowed by the jungle, revealing secrets of an ancient Indigenous culture that could be over 1,000 years old.

Related: History's 10 most overlooked mysteries

The La Mosquitia region spans over 1,350 square miles (3,500 square kilometers) and is one of the most pristine lowland rainforest areas in Central America, supporting Honduras' biggest biodiversity hotspots, according to Conservation International.

However, the region is currently threatened by illegal logging and wildlife trafficking, creating serious risks not only for local habitats and biodiversity but also for the preservation of important archaeological sites that could become vulnerable to looting, filmmaker and explorer Doug Elkins told Live Science. Elkins was part of the team that discovered the ruins of what is thought to be the White City, in collaboration with the government of Honduras and Honduran scientists.

In the 1940s, an American explorer named Theodore Morde returned from an expedition to La Mosquitia with thousands of artifacts; he declared that he had discovered the legendary city and that Indigenous people described an enormous statue of a monkey god that had been buried there, according to National Geographic.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Elkins' fascination with the White City began in the 1990s, when he first heard about the city while working as a television producer. During subsequent visits to Honduras, he saw evidence in the jungle that further piqued his interest.

"We were up in the mountains, many days by canoe ride from civilization, and we stumbled upon this huge boulder with a petroglyph: a man with a mask or helmet on, holding a stick and a sack with what looked like seeds coming out of it," he said.

"The rainforest was so thick, you could barely see more than 20 feet [6 meters] in front of you," Elkins said. "Who would have gone to the trouble to make such an exquisite carving on a boulder if there was nothing going on in this area?" That detailed petroglyph, he said, suggested that there were once human settlements in the area, even if no sign of them was presently visible.

Hidden settlements

In 2012, using a technique called light detection and ranging, or lidar, Elkins found further clues about the possible location of an ancient city in a large depression in a forest surrounded by mountains. As the survey plane flew over the jungle, laser pulses pinged off the ground and measured the heights of structures that were hidden beneath dense jungle cover, so that engineers could reconstruct the topography in 3D. Digital 3D maps of the ground then removed the tree cover to show the hidden shapes more clearly, revealing what appeared to be building foundations, agricultural terraces, roads and canals, Live Science reported in 2013.

Elkins then filmed the arduous 2015 expedition to the site. The team included filmmakers, scientists, a lidar engineer, jungle warfare survival specialists and more than a dozen Honduran special forces soldiers providing security, National Geographic reported that year. Hiking to the remote location brought challenges that tested the group to their limits, such as encounters with venomous snakes, quicksand, swarms of biting insects and even flesh-eating bacteria, Douglas Preston, team member and author of "The Lost City of the Monkey God: A True Story" (Grand Central Publishing, 2017), told the CBC in 2017.

The group's perseverance paid off. Deep in the jungle, the researchers found mounds, plazas, vessels carved with vultures and snakes, and a pyramid with a cache of stone sculptures buried at its base, according to National Geographic.

Team member Oscar Castro, archaeology department chief of the Honduran Institute of Anthropology and History (IHAH), dated the objects to A.D. 1000 to 1400. One stone figure, buried with its head sticking out of the ground, could be a "were-jaguar," which is thought to be a representation of a shaman's spiritual state during a ritual transformation, expedition member Christopher Fisher, a Mesoamerican archaeologist and professor of anthropology at Colorado State University, told National Geographic.

But was this truly the fabled White City that inspired tales of monkey gods and lost treasures? That conclusion is still debatable, as many such settlements once extended across the La Mosquitia region, Castro told Spanish news agency Agencia EFE in 2015. Today, much of the Honduran rainforest likely conceals evidence of numerous ancient ruins that have not been explored or mapped because of their remote locations and limited government resources; many of these ruins could represent cultures that are still unknown to modern archaeologists, Castro said.

On that point, Elkins agrees. "I'm thoroughly convinced that the entire jungle was probably urbanized at one time," Elkins said. Indeed, in 2018, lidar scans of the Guatemalan jungle revealed that the region once held vast Maya cities with more than 60,000 homes, roads, palaces and ceremonial buildings, Live Science reported that year. The findings confirmed that approximately 11 million Maya people lived in the region from A.D. 650 to 800, according to a study published in 2018 in the journal Science.

The remains of other ancient civilizations are likely still concealed by dense jungle cover, Elkins said.

"Lost City of the Monkey God" premieres Oct. 31 at 8 p.m. ET/PT on the Science Channel.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus