10 stunning swords and other ancient weapons uncovered in 2021

Rusty swords, biblical arrowheads, non-returning boomerangs and more.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Archaeologists have made some remarkable finds this year, from barnacle-encrusted Crusader swords at the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea to non-returning boomerangs in South Australia. In this countdown, we pick 10 of our favorite sword and weapons discoveries from 2021.

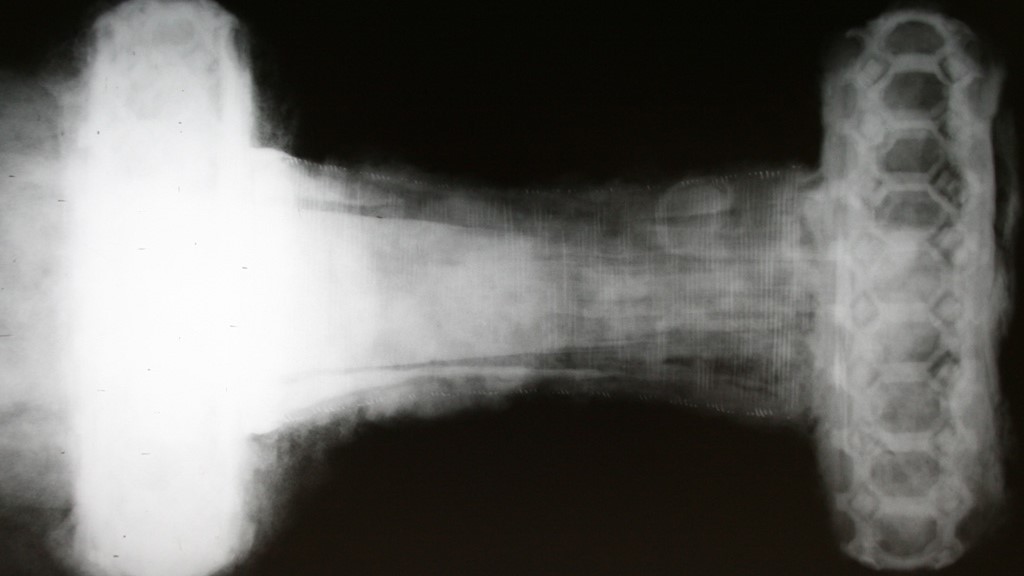

Viking sword X-ray

In December, archaeologists used X-rays to uncover the ornate hilt of a Viking sword that was highly corroded and covered in dirt. The new images show the weapon in a new light and reveal its striking design.

The sword is part of a hoard of Viking treasures unearthed in 2015 at a burial site on one of the Orkney Islands, north of mainland Scotland. The weapon was in very poor condition, and archaeologists were scared that removing the rust and dirt would irreparably damage the sword. They decided that the only way they could see what the sword originally looked like was by analyzing it using X-rays.

The X-ray images revealed that the sword was actually "highly decorated" with a complex honey-comb pattern, made up of octagons and lozenges (diamond shapes), on the sword's guard. Researchers also found partial remains of a wooden scabbard mineralized onto the sword's blade.

Read more: X-ray analysis reveals 'highly decorated' Viking sword caked in dirt and rust

Ornate Roman dagger

In November, an amateur archaeologist with a metal detector in Switzerland discovered an ornate dagger that belonged to a Roman soldier 2,000 years ago.

The finding led a team of archaeologists to the site, who then uncovered hundreds of artifacts from a "lost" battlefield where Roman legionaries fought Rhaetian warriors as Rome sought to consolidate power in the area.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Archaeologists think one of those legionaries may have buried the dagger intentionally after the battle as a token of thanks for victory. Only four similar daggers — each sharing distinctive features like cross-shaped handles — have ever been found in former Roman territories.

Read more: Metal detectorist finds 2,000-year-old dagger wielded by Roman soldier in battle with Rhaetians

Biblical arrowheads

In May, archaeologists unearthed a bone arrowhead in the ancient Philistine city of Gath, which was supposedly the home of Goliath, the giant warrior killed by King David.

According to the Hebrew Bible, a king named Hazael, who ruled the kingdom of Aram from around 842 B.C. to 800 B.C., conquered Gath (also known as Tell es-Safi) before marching on Jerusalem. "Hazael king of Aram went up and attacked Gath and captured it. Then he turned to attack Jerusalem," the Book of Kings says (2 Kings 12:17).

Archaeologists think the arrowhead, which was found in the remains of a street in the lower city, may have been fired by the city's defenders in a desperate attempt to stop Hazael's forces from taking the city.

Read more: Arrowhead from biblical battle discovered in Goliath's hometown

Folded sword

In May, archaeologists in Greece discovered a 1,600-year-old iron sword that had been folded in a ritual "killing" before being interred in the grave of a soldier who served in the Roman army.

The sword and its owner were discovered in a paleochristian basilica, dating back to the fifth century, in Thessaloniki in Greece. The basilica was discovered in 2010, during excavations ahead of the construction of a subway track, which prompted researchers to call the ancient building the Sintrivani basilica, after the Sintrivani metro station.

Despite the man being buried in a church, the sword folding was a part of a known pagan ritual, which suggests the soldier may not have originally been Roman, as the Roman empire had embraced Christianity by that time. The bent sword is a clue that the soldier was a "Romanized Goth or from any other Germanic tribe who served as a mercenary (foederatus) in the imperial Roman forces," Errikos Maniotis, a co-researcher on the project and a doctoral candidate in the Department of Byzantine Archaeology at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece, told Live Science at the time.

Read more: 'Folded' iron sword found in a Roman soldier's grave was part of a pagan ritual

Non-returning boomerang

In November, a new study into five rare "non-returning" boomerangs found in a dry riverbed in South Australia revealed they were probably used by the Aborigines to hunt waterbirds hundreds of years ago.

Radiocarbon dating revealed that Aborigines crafted the boomerangs from wood between 1650 and 1830 — before the first Europeans explored the area. In addition to hunting, researchers also suspect the boomerangs could have been used to dig, stoke fires and perform ceremonies, as well as be used in hand-to-hand combat.

Because Aboriginal boomerangs are made from wood, they quickly decompose when exposed to the air. This is only the sixth time that any have been found in their archaeological context. "It's especially rare to have a number of them found at once like this," Amy Roberts, an archaeologist and anthropologist at Flinders University in Adelaide, told Live Science at the time.

Read more: 5 non-returning Aboriginal boomerangs discovered in dried-up riverbed

Barnacle-encrusted Crusader sword

In October, a scuba diver off the coast of Israel discovered a trove of 900-year-old artifacts on the Mediterranean Sea bed, including a 900-year-old barnacle-encrusted sword that likely belonged to a knight during the region's bloody crusader period.

"The sword, which has been preserved in perfect condition, is a beautiful and rare find and evidently belonged to a Crusader knight," Nir Distelfeld, inspector for the Israel Antiquities Authority's Robbery Prevention Unit, said in a statement. "It is exciting to encounter such a personal object, taking you 900 years back in time to a different era, with knights, armor and swords."

The sword, which was "encrusted with marine organisms," is believed to be made of iron and measure approximately 3.3 feet (1 meter) long, with a hilt measuring an additional 1 foot (30 centimeters) in length.

Read more: 900-year-old Crusader sword discovered off coast of Israel

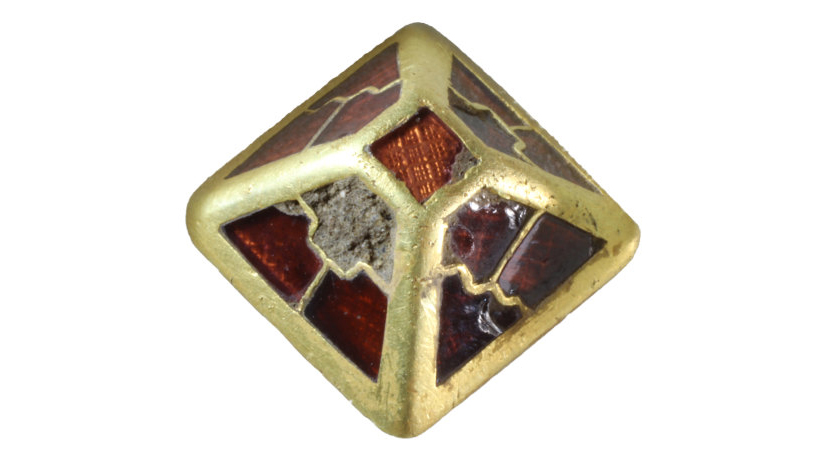

Sword pyramid

In August, a metal detectorist in England discovered a tiny pyramid-shaped artifact that would have once adorned the elaborate scabbard of an elite warrior.

The 1,400-year-old sword pyramid is about 0.24 inches (6 millimeters) high and 0.47 inches (12 mm) long at its base. It was found in a place where no archaeological site is known to exist, and experts believe it likely fell off its owner’s scabbard and was lost.

"There is no archaeological site associated with the find," Helen Geake, a national finds adviser with the Portable Antiquities Scheme, run by the British Museum and National Museum Wales, told Live Science at the time. "It seems to have been randomly lost in the middle of nowhere, not buried, and not put out with the rubbish in a crowded settlement."

Read more: Metal detectorist finds sword pyramid from time of mysterious Sutton Hoo burial

Grunwald sword

In April, a metal detectorist in Poland unearthed a medieval sword that might have been used during the Battle of Grunwald in 1410.

The Battle of Grunwald was contested between a joint Polish-Lithuanian army and the Knights of the Teutonic Order, which was founded during the Crusades to the Holy Land and later came to rule over what was then Prussia. About 13,000 of the 66,000 troops on both sides died during the bloody battle.

The sword was found alongside a scabbard, a belt and two knives. Despite spending 600 years buried, the artifacts were all very well preserved.

Read more: Medieval sword unearthed in Poland might be from Battle of Grunwald

Greek helmet

In March, an ancient bronze helmet, which was likely worn by a Greek soldier during a war with the Persians, was found in a harbor in Israel.

The "helmet probably belonged to a Greek warrior stationed on one of the warships of the Greek fleet that participated in the naval conflict against the Persians who ruled the country at the time," Kobi Sharvit, director of the Israel Antiquities Authority marine unit, said in a statement.

"The helmet is a Corinthian type named after the city of Corinth in Greece where it was first developed and produced in the 6th century [B.C.]," the researchers said. The helmet was made out of a single sheet of bronze that was heated and hammered into shape, which made it lighter than other helmets without reducing the protection it offered.

Read more: Ancient helmet worn by soldier in the Greek-Persian wars found in Israel

Mysterious stone balls

In September, two polished stone balls, dating to around 5,500 years ago, were discovered in an ancient tomb on the island of Sanday, in the Orkney Islands north of mainland Scotland.

Hundreds of similar stone balls, each about the size of a baseball, have been found at Neolithic sites mainly in Scotland and the Orkney Islands, but also in England, Ireland and Norway, Live Science previously reported.

Researchers had previously suggested that the balls were used as weapons, and so they were sometimes called "mace heads" as a result. But most archaeologists now think the stone balls were made mainly for artistic purposes.

Read more: Mysterious stone balls found in Neolithic tomb on remote Scottish island

Originally published on Live Science.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus