'Folded' iron sword found in a Roman soldier's grave was part of a pagan ritual

The "killed" sword is about 1,600 years old.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Archaeologists in Greece have discovered a 1,600-year-old iron sword that was folded in a ritual "killing" before being interred in the grave of a soldier who served in the Roman imperial army.

The discovery of the folded sword was "astonishing," because the soldier was buried in an early church, but folded sword was part of a known pagan ritual, said project co-researcher Errikos Maniotis, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Byzantine Archaeology at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece.

Although this soldier, who was likely a mercenary, may have "embraced the Roman way of life and the Christian religion, he hadn't abandoned his roots," Maniotis told Live Science in an email.

Related: Photos: Decapitated Romans found in ancient cemetery

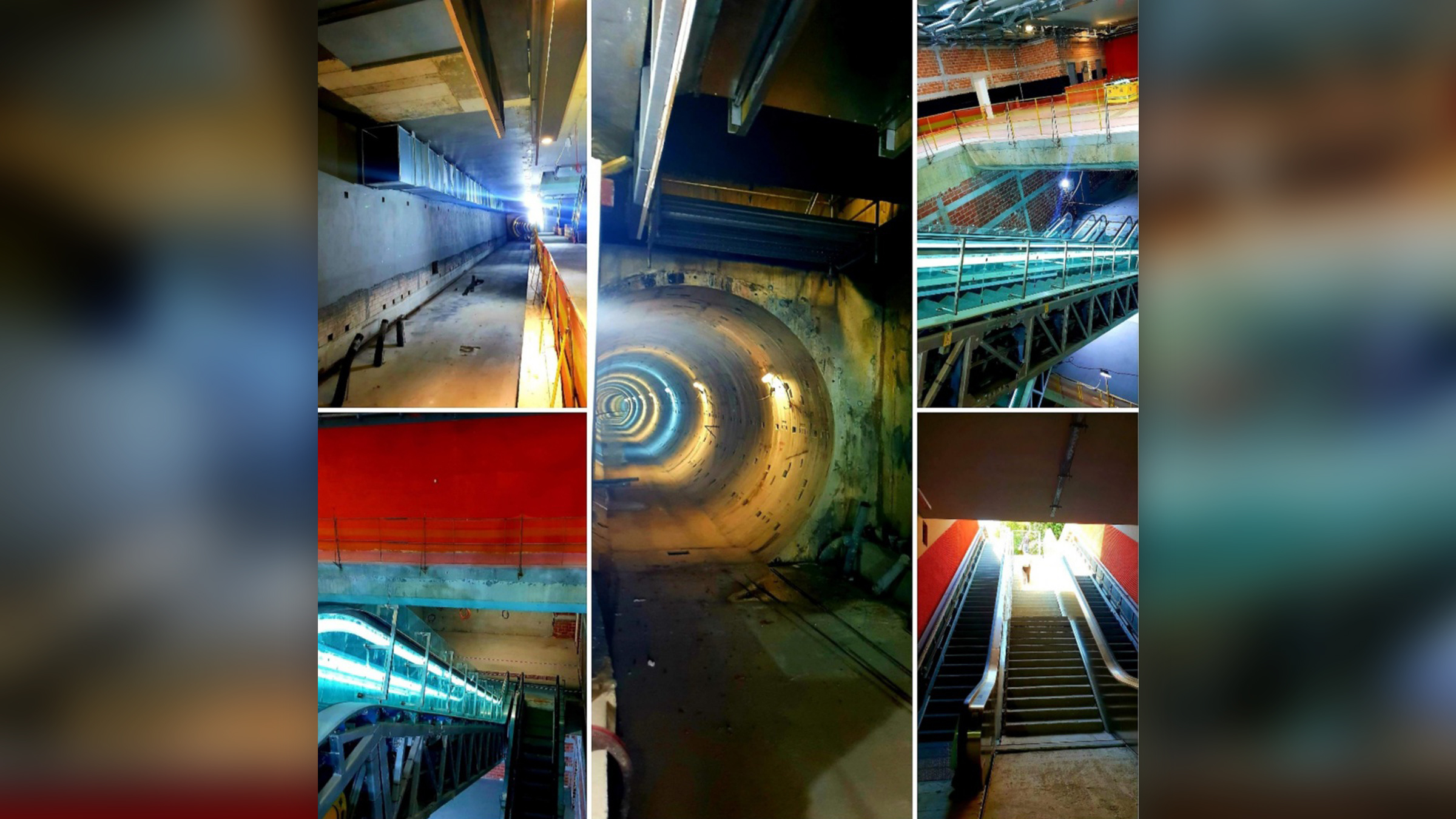

The soldier's burial is the latest finding at the site of a three-aisled paleochristian basilica dating from the fifth century. The basilica was discovered in 2010, during excavation ahead of the construction of a subway track, which prompted researchers to call the ancient building the Sintrivani basilica, after the Sintrivani metro station. The station is in the northern Greek city of Thessaloniki, which was an important metropolis during Roman times.

The basilica was built over an even older place of worship; a fourth-century chapel, which might be the oldest Christian church in Thessaloniki, Maniotis said.

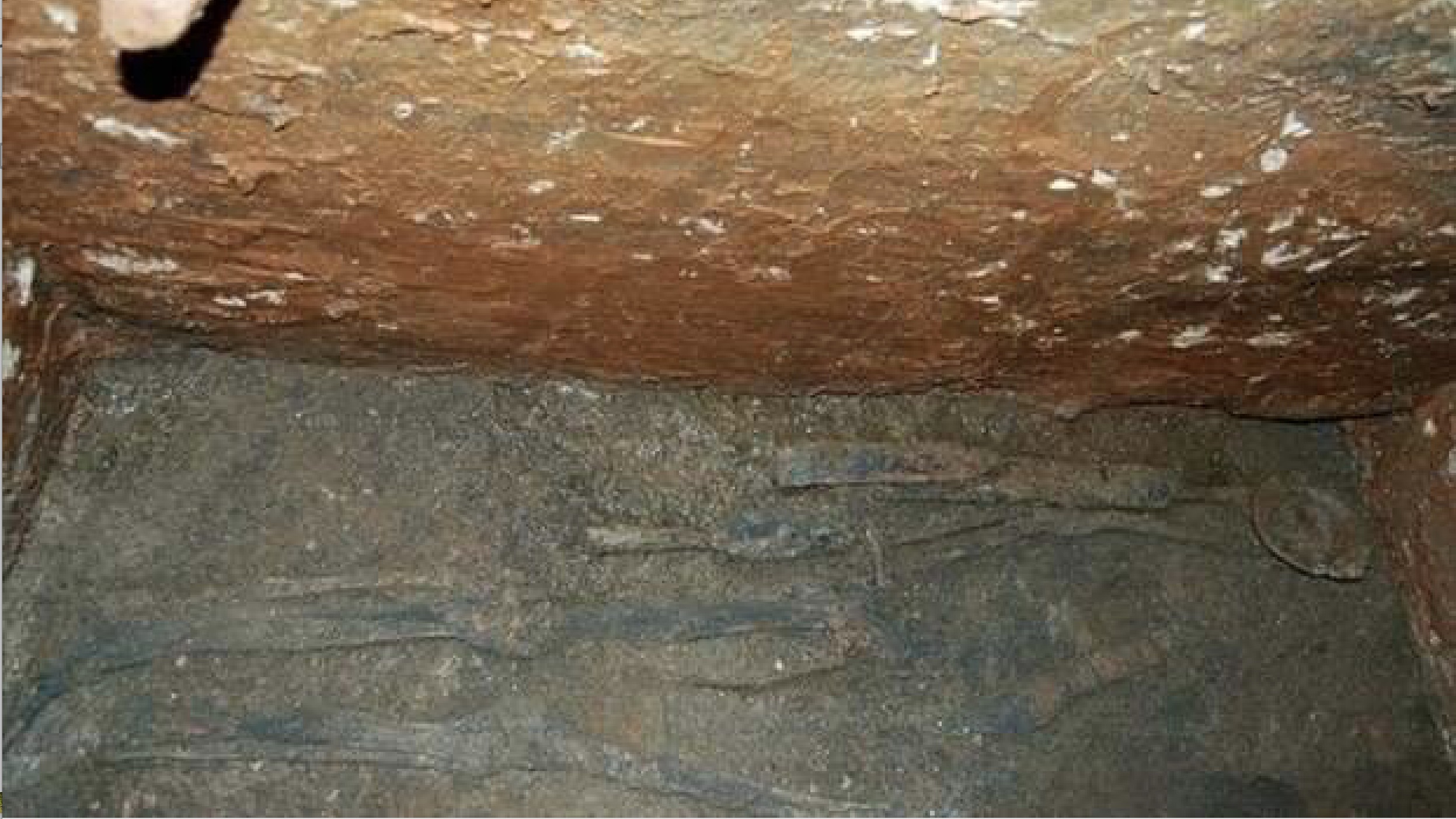

In the seventh century, the church was damaged and only poorly renovated before it was eventually abandoned in the eighth or ninth century, Maniotis said. During recent excavations, archeologists found seven graves that had been sealed inside. Some of the graves contained two deceased individuals, but didn't have any artifacts. However, an arch-shaped grave contained the remains of an individual who had been buried with weapons, including a bent spatha — a type of long, straight sword from the late Roman period (A.D. 250-450).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Usually, these types of swords were used by the auxiliary cavalry forces of the Roman army," Maniotis said. "Thus, we may say that the deceased, taking also into consideration the importance of the burial location, was a high-ranking officer of the Roman army."

The archaeologists still have to study the individual. "We don't know anything about his profile: age of death, cause of death, possible wounds that he might have from the wars he fought, etc.," Maniotis said. However, they were intrigued by his folded sword and other weapons, which included a shield-boss (the circular center of a shield) and spearhead.

So far, the folded sword is the most revealing feature in the grave. "Such findings are extremely rare in an urban landscape," Maniotis said. "Folded swords are usually excavated in sites in Northern Europe," including in places used by the Celts, he said. This custom was also observed in ancient Greece and much later by the Vikings, but "it seems that Romans didn't practice it, let alone when the new religion, Christianity, dominated, due to the fact that this ritual [was] considered to be pagan," Maniotis said.

The bent sword is a clue that the soldier was a "Romanized Goth or from any other Germanic tribe who served as a mercenary (foederatus) in the imperial Roman forces," Maniotis wrote in the email. The Latin word "foederatus" comes from "foedus," a term describing a "treaty of mutual assistance between Rome and another nation," Maniotis noted. "This treaty allowed the Germanic tribes to serve in the Roman Army as mercenaries, providing them with money, land and titles. [But] sometimes these foederati turned against the Romans."

Related: In photos: A journey through early Christian Rome

The archaeological team recently found ancient coins at the site, so they plan to use these, as well as the style of the sword's pommel, or the knob on the handle, to figure out when this soldier lived, Maniotis noted.

"The soldier's armament [weapons] will shed light to the impact that the presence of the community of foreign mercenaries had in the city of Thessaloniki, the second greatest city, since the fall of Rome and after Constantinople, in the Eastern Roman Empire."

Mosaic and cemetery

The discovery of the ancient basilica has revealed other ancient artifacts. Archaeologists led by Melina Paisidou, an associate professor of archaeology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, have also excavated the building's beautiful mosaic floor, Maniotis said. The mosaic shows a vine with birds on its stalks, including the mythical phoenix with a halo that has 13 rays at its center. Only seven other depicted birds have survived, but the archaeological team posits that there were originally 12 birds, and that the mosaic is likely an allegorical representation of Christ and the 12 apostles, Maniotis said.

In addition, a discovery at the site in 2010 revealed about 3,000 ancient burials in Thessaloniki eastern cemetery, a burial ground that was used from the Hellenistic period (about 300-30 B.C.) until just before late antiquity (A.D. 600-700), according to Ancient Origins.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus