Sue the T. rex had a terribly painful infection when she died

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

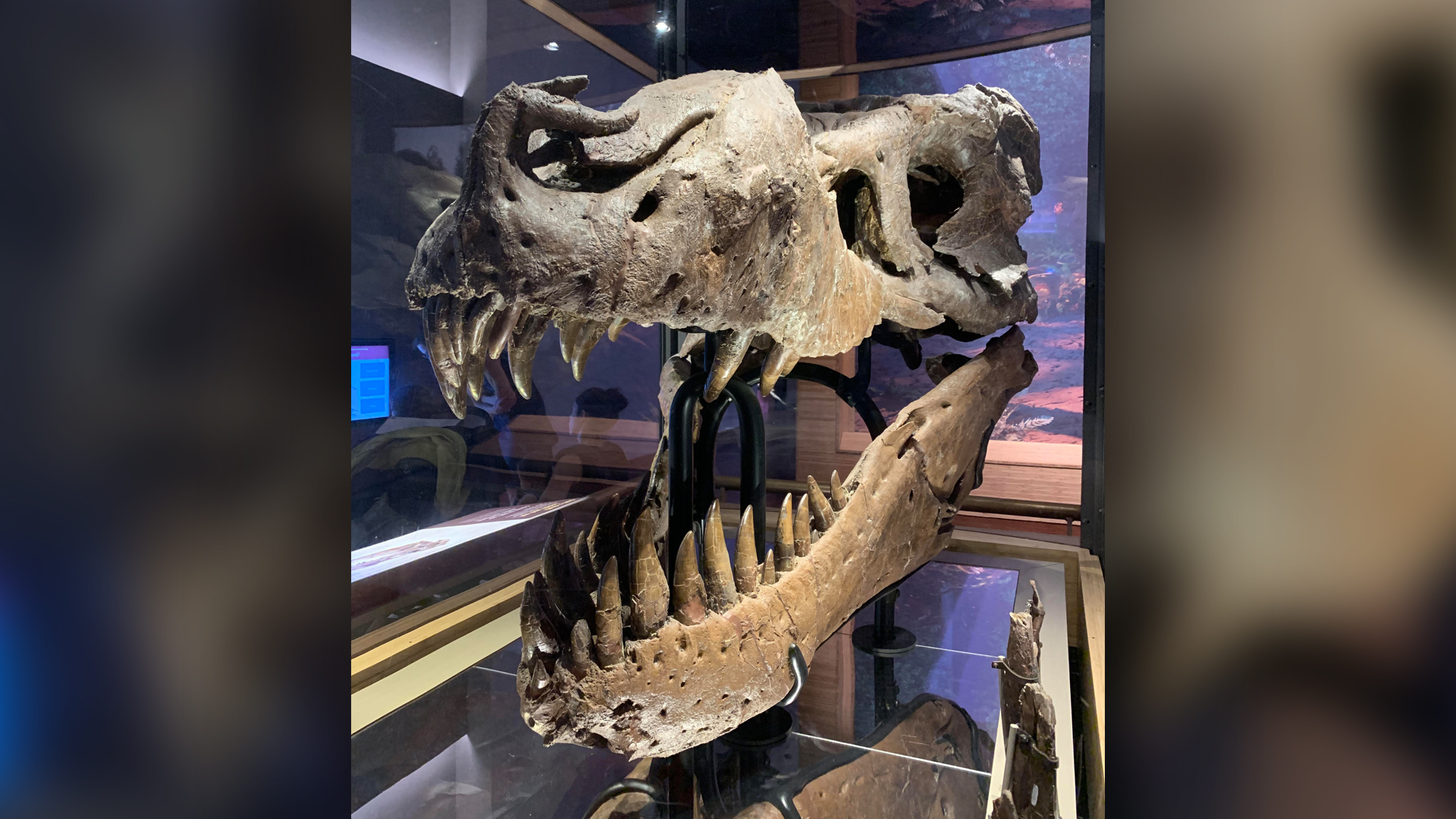

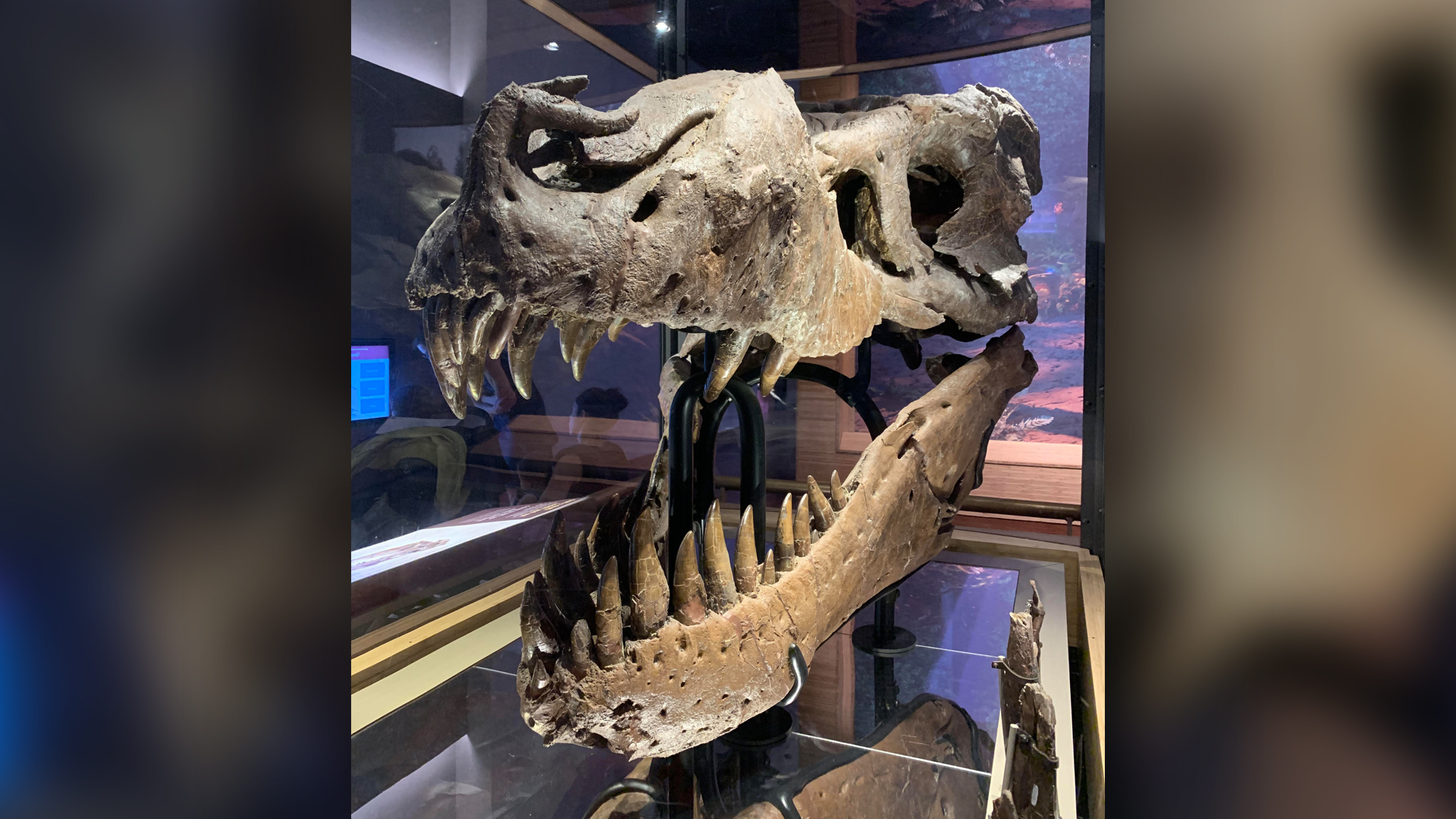

Sue, the mighty Tyrannosaurus rex whose skeleton is one of the most complete ever found, likely suffered from a big toothache due to three tiny, weird-looking teeth.

"Two of these teeth are actually fused together," said study lead researcher Kirstin Brink, an assistant professor in the Department of Geological Sciences at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, Canada. "One of the teeth has some extra serrations on the side of the tooth, not in the normal place on the front or back edges of the tooth."

Her research, which is not yet published in a peer-reviewed journal, was presented online Oct. 13 at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology annual conference, held online this year due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Related: Photos: Newfound tyrannosaur had nearly 3-inch-long teeth

Like other T. rexes, Sue, whose skeleton is on display at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, had knifelike serrated teeth, some the size of bananas. When alive, T. rexes would constantly grow new teeth, likely replacing each tooth every one to two years.

While dental problems were common in theropods, the group of bipedal, mostly-meat eating dinosaurs that includes T. rex, most of those tooth troubles were likely genetic, Brink said. In contrast, Sue's three developing teeth are weirdly misshapen, "squished and bent with a strange, almost wave-like texture running down the sides, almost as if they were like icing being squeezed through a piping bag," Brink said.

Previously, researchers examining strange holes in Sue's jaw diagnosed the dinosaur king with trichomonosis (also called trichomoniasis), an oral infection caused by a parasite, according to a 2009 study published in the journal PLOS One. Now, Brink's research suggests that this condition may have changed the shape of Sue's teeth; this would be the first record of an infection causing misshapen teeth in a theropod, she said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Brink came to that conclusion after looking at digital 3D images from CT (computed tomography) scans of the teeth. Because this weird, fused-tooth formation wasn't seen elsewhere in Sue's chompers — "Sue's teeth are all normal except for the three odd ones" — this deformity likely isn't a genetic blip, Brink said.

She noted that when modern birds, the descendants of theropod dinosaurs, get trichomonosis, "they grow large, waxy growths in their throats. The infection can also spread through the skull and through the skin, so a lot of tissues in the head can be affected." Modern birds don't have teeth, however, so it's hard to know how this infection would affect teeth. However, "my working hypothesis at this point is that the waxy growths got so big or the infection got so bad that normal tooth development was disrupted in one spot in the jaw," of Sue, she said.

This type of tooth malformation is also seen in teeth of the megalodon shark, another prehistoric creature that also constantly regrew its teeth, said Ashley Poust, a postdoctoral researcher at the San Diego Natural History Museum, who wasn't involved with the research.

T. rexes wouldn't have minded malformed teeth too much — after all, they were always growing new teeth. "If the tissues that grow the teeth were damaged though, then the T. rex might have been in a world of hurt," Poust told Live Science in an email. "An impacted or malformed tooth could have been a source of real misery."

Evan Johnson-Ransom, a master's student at Oklahoma State University specializing in the feeding behavior of theropod dinosaurs, remembers how, when he would give tours as a docent at the Field Museum, "I always talked about the holes in Sue's jaw being the result of an infection, and how difficult it was for Sue to eat and drink."

"Upon hearing Dr. Kirstin Bink's research on Sue's infection, I was both fascinated and terrified at how far the infection could spread and the effect it had on its teeth generation," Johnson-Ransom, who wasn't involved in the research, but saw the presentation at the conference, told Live Science. "Research like this shows us not only how prehistoric animals lived, but also the injuries they sustained and how much … it affected them."

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus