10 scorching-hot discoveries made about the sun in 2023

From a surprisingly active solar cycle to finding evidence of ancient superflares and solar auroras, here are the most exciting discoveries about the sun made this year.

In addition to being the largest and most powerful object in the solar system, the sun is also one of the most enigmatic entities in our cosmic neighborhood, which makes it hard for researchers to pin down exactly how it works. We are constantly learning new things about our home star, and 2023 has been no different. From learning more about the upcoming solar maximum to uncovering ancient superflares and mysterious heartbeat signals, here are the top 10 things we've learned about the sun this year.

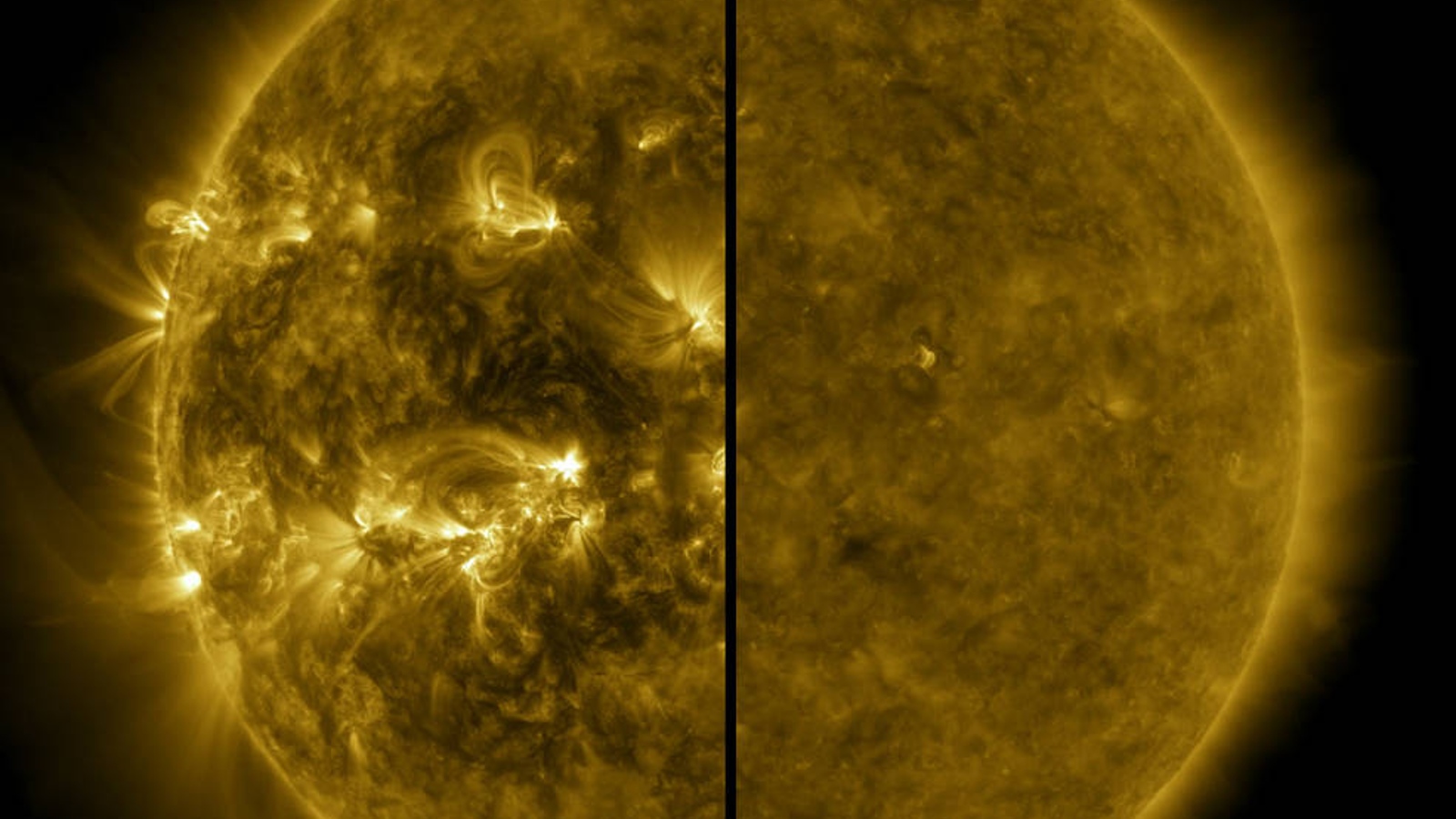

Solar maximum is right around the corner

The major news about the sun from this year is that we are fast approaching the solar maximum and that it's going to be more explosive than we initially thought.

Back when the current solar cycle began in 2019, forecasts from space weather scientists suggested that the solar maximum would arrive sometime from 2025 onward and be relatively weak compared to past solar cycles. However, numerous warning signs early in the year, including rising sunspot numbers, powerful X-class solar flares and changes in Earth's upper atmosphere, hinted that the solar cycle was not progressing as expected.

In June, Live Science published an exclusive, in-depth feature on the upcoming solar maximum, which revealed that the explosive peak would likely arrive by 2024 and be more active than the initial forecast suggested. And in October, space weather scientists released an updated forecast for the current solar cycle, which is more in line with what experts told Live Science.

When solar maximum does arrive, we can expect to be bombarded with more solar storms, which will result in frequent auroral displays, radio blackouts, potential satellite problems and disruptions to the migration patterns of some animals.

The sun is smaller than we realized

The outer edge of the sun's atmosphere, or corona, does not extend out quite as far as we previously thought, a study published in November revealed.

Until recently, the best way to measure the sun's corona was to observe it during a solar eclipse when it becomes clearly visible around the moon. But new technologies have allowed scientists to measure the oscillations, or waves, that travel through the corona. These waves do not travel quite as far as expected.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The difference between the new findings and previous estimates is relatively small: The sun is likely somewhere between 0.03% and 0.07% smaller than we thought. However, scientists say this could make a big difference in how we study our star.

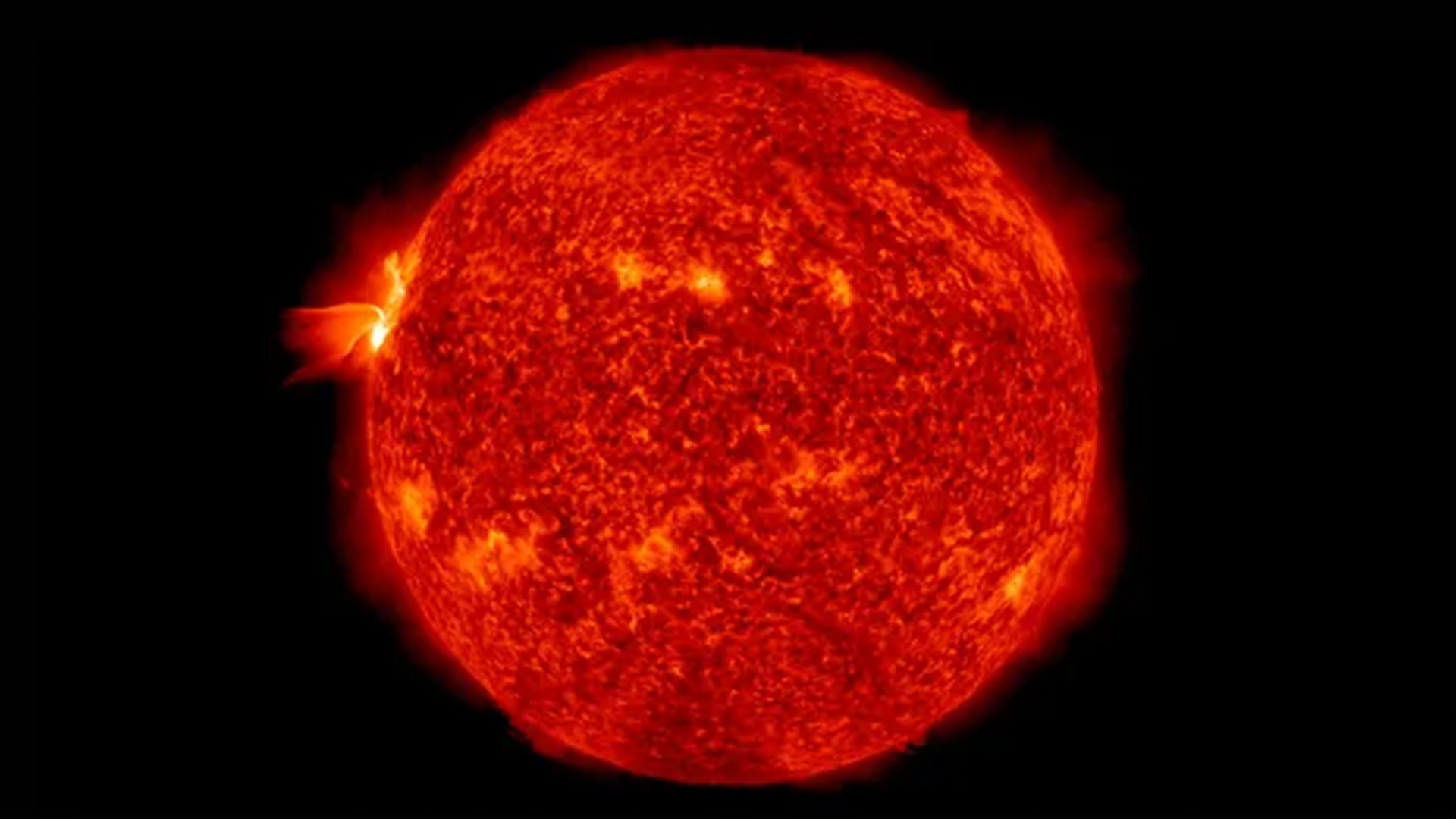

The sun has auroras too

Within the solar system, auroras were previously thought to only occur on some planets and moons. But a study from November revealed that the sun also has auroras (although they are a little different from the ones we see on Earth).

Astronomers detected radio bursts crackling above a sunspot after pointing a radio telescope at the dark patch. The frequencies of the radio waves were very similar to the wavelengths given off by auroras on Earth, which strongly suggests a similar process is occurring on the sun.

On Earth, auroras are born when solar storms and solar wind bash into our planet and temporarily weaken our magnetic shield, which allows radiation from the sun to excite gas molecules in the upper atmosphere. However, researchers think that solar auroras are created by electrons that are accelerated to incredibly high speeds along the sun's magnetic field lines instead.

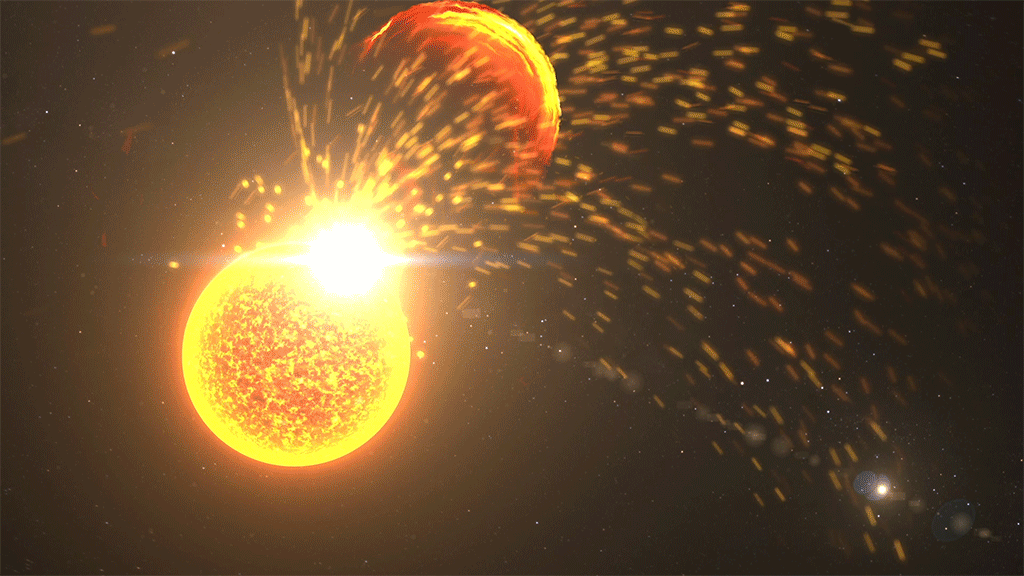

Biggest-ever solar storm unearthed

In October, researchers revealed that a superpowered solar storm, known as a Miyake Event, slammed into Earth around 14,000 years ago. And it could have been the most powerful solar outburst to ever hit Earth, experts said.

Researchers found evidence of the cataclysmic event lurking within fossilized tree rings that were recently unearthed in the French Alps. The preserved plants all had off-the-chart levels of radiation in the same rings, which showed they all soaked up the radiation at the same time — and only a powerful Miyake Event could explain the levels of radiation the team found.

"A similar solar storm today would be catastrophic for our modern technological society," the researchers wrote.

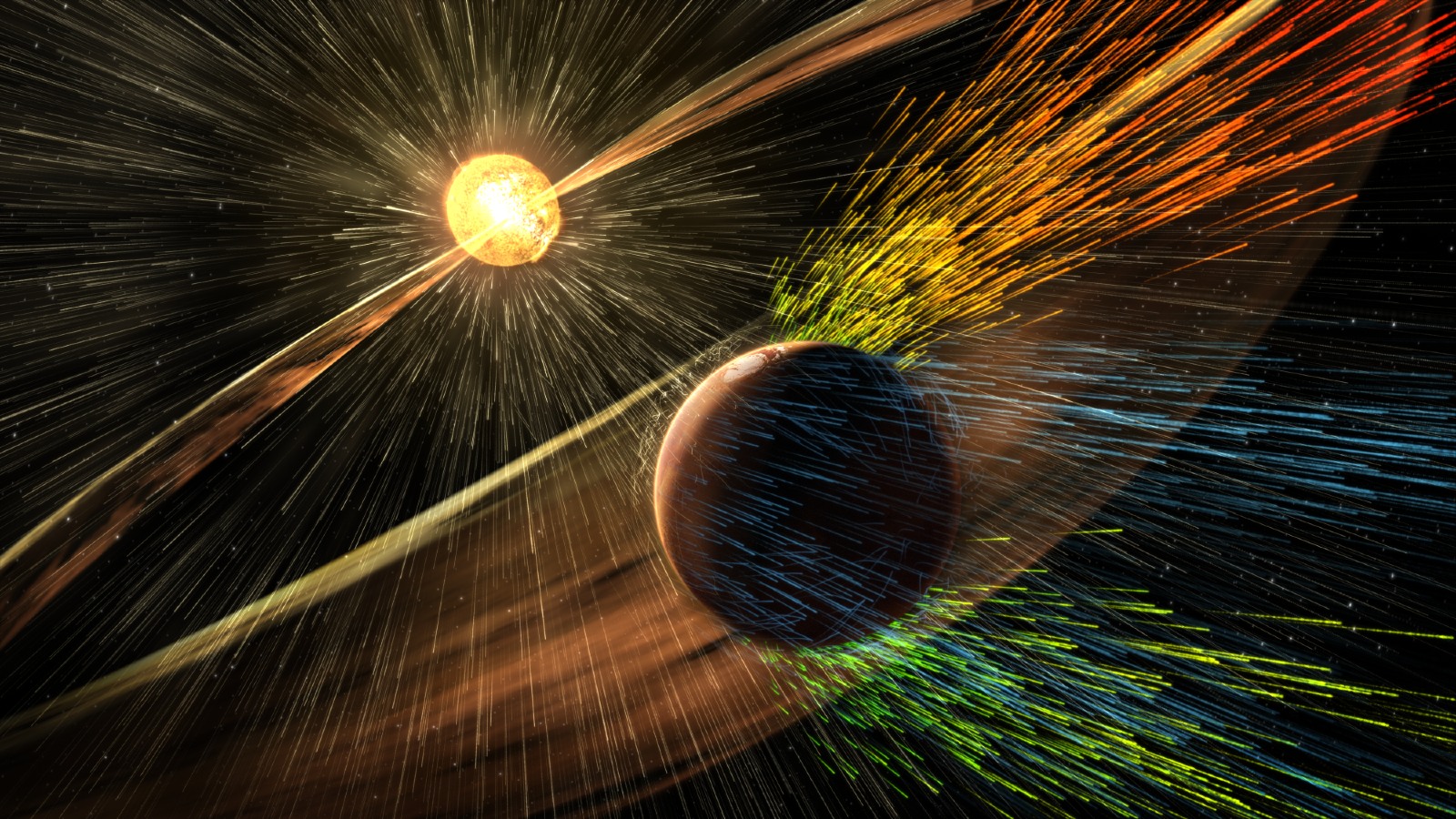

Ancient 'superflares' may have sparked life on Earth

Continuing the ancient solar storm trend, a May study revealed that "superflares" from the early hyperactive sun could have provided the energy needed to spark life on Earth billions of years ago.

Researchers recreated Earth's early atmosphere in the lab and fired charged particles, like those found in solar wind, at the primitive gasses and found that this created both amino acids and carboxylic acids — building blocks for proteins and all organic life.

Similar experiments recreating lightning have also created these compounds in the lab. But the team argues that lightning strikes would not have provided anywhere near as much power as superflares, which makes them a less suitable candidate for kickstarting life on Earth.

However, much more work is needed before any concrete conclusions can be made.

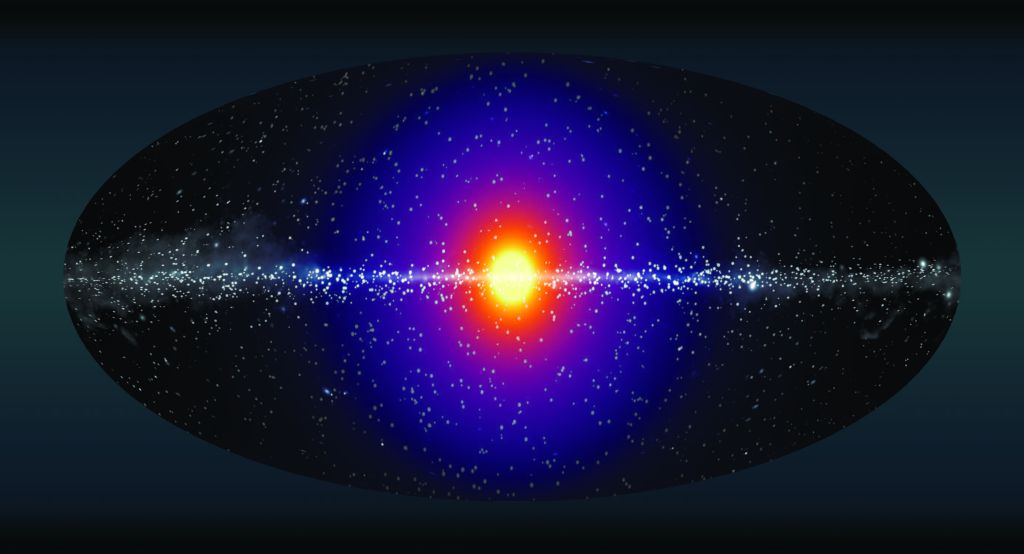

'Ghost particles' could reveal hidden dark matter

The sun may be harboring hidden particles of dark matter in its fiery guts and neutrinos, or "ghost particles" that are spat out by the sun, could be the key to finding them, a pre-print paper published in August suggested.

Dark matter is an elusive type of matter whose identity is still a mystery to scientists. Dark matter rarely interacts with regular matter or light but when it does it is theorized to emit neutrinos, which have almost no mass and no electrical charge.

Researchers hypothesized that the sun's core may have a high concentration of dark matter and, if this is the case, they predict that it will occasionally emit slightly more neutrinos than normal. However, these extra neutrinos have not been detected so far.

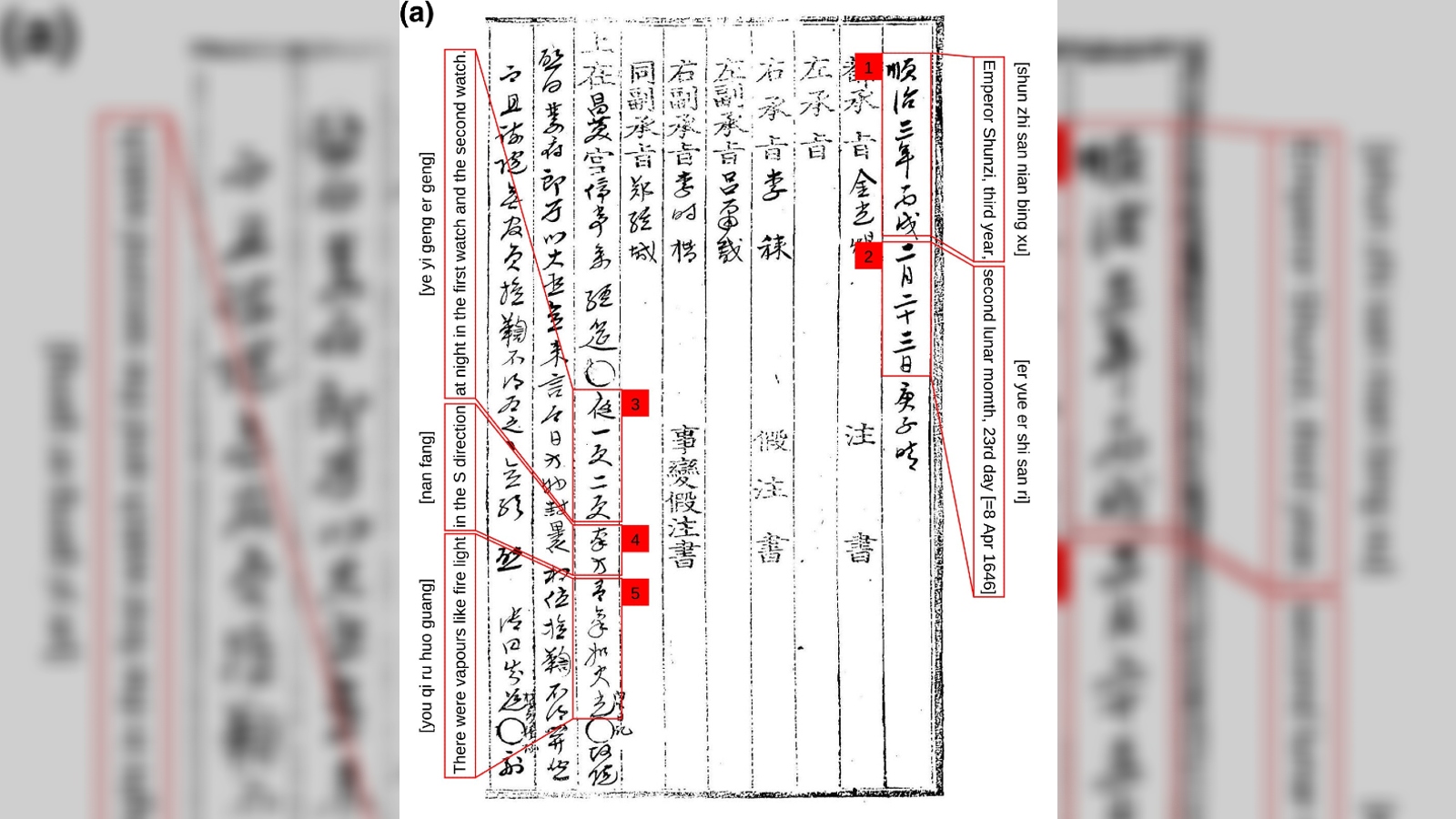

Ancient anomaly in sun's solar cycle

It currently takes around 11 years for the sun to complete one solar cycle, during which it transitions from solar minimum to solar maximum and back again. But a pre-print paper published in June suggests that past cycles may have been much shorter.

Researchers studied ancient texts unearthed in Korea, which contain detailed accounts of auroral displays during the Maunder Minimum — a period of reduced solar activity between 1645 and 1715. They found that solar cycles during this time likely lasted only eight years.

However, scientists have not been able to properly explain why the solar cycle shortened during this period.

Mysterious 'heartbeat' puzzle solved

For more than a decade, scientists have pondered the origins of mysterious heartbeat-like patterns within streams of electromagnetic radiation that shoot out of the sun during solar flares.

The streams of radiation, known as solar radio bursts, normally flow non-stop out of the sun. But sometimes, there are fluctuations or gaps in the stream, known as quasi-periodic pulsations, which when viewed on a graph look similar to an electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG) of a human heart.

Earlier this year, scientists studied some of these mysterious patterns produced during a 2017 solar flare. They found that the patterns were created by fluctuations within invisible fields of electrical current that run across loops of plasma on the solar surface.

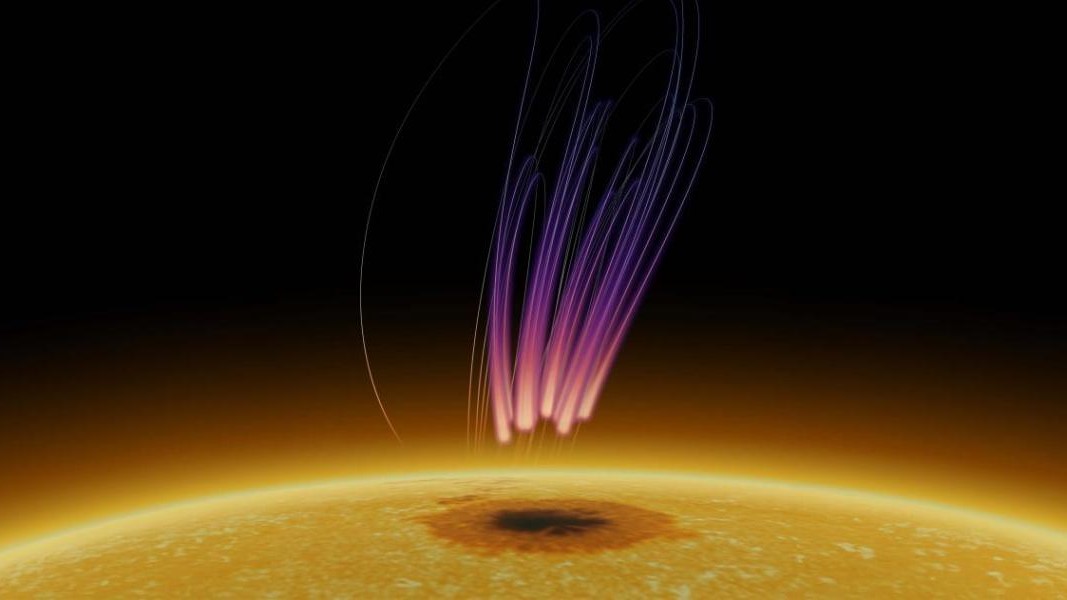

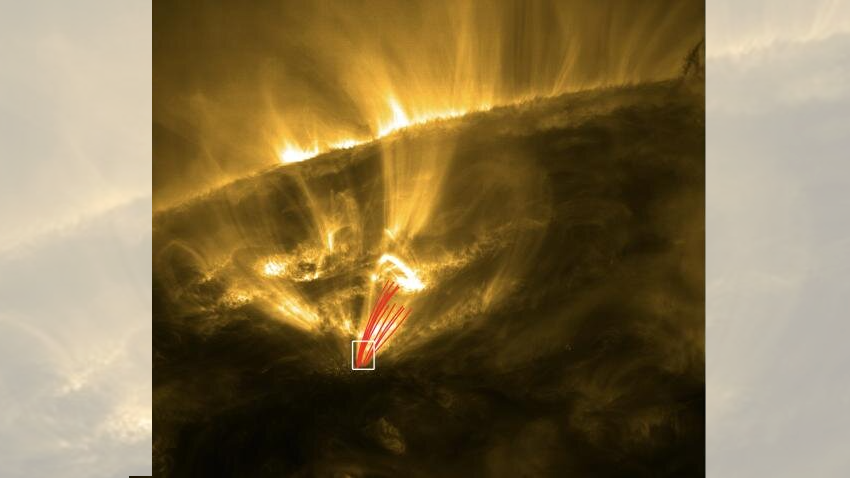

The sun has shooting stars

In July, scientists announced the discovery of a new feature in the sun's corona — shooting stars.

These "stars" are clumps of plasma that fall through the sun's upper atmosphere, like meteors falling to Earth, because they are cooler than the surrounding plasma and, therefore, denser.

These dense plasma balls can reach up to 435 miles (700 kilometers) across and seem to fall along magnetic field lines created on the sun's surface. Scientists dubbed this phenomenon coronal rain.

Mini solar wind 'jets' discovered

In August, scientists got a step closer to finally uncovering the origin of large outflows of solar particles, known as solar wind, that shoot out of the sun's corona.

The European Space Agency's Solar Orbiter spotted tiny jets of plasma, known as picojets, shooting from tiny dark spots on the sun, known as coronal holes. The mini jets are smaller than other solar jets but still pack a punch, and researchers think that they provide the necessary energy to trigger gusts of solar wind.

Picojets could also explain why the outer corona is hotter than scientists expect it to be.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus