Oops! US Space Force may have accidentally punched a hole in the upper atmosphere

A rocket carrying a Space Force surveillance satellite may have created a hole in the ionosphere as it shot into space. The launch was carried out with just 27 hours' notice, which is a new record.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A rocket carrying a U.S. Space Force satellite into orbit may have punched a hole in Earth's upper atmosphere, after lifting off with just 27 hours' notice — a new record for the shortest amount of time from getting the go-ahead to actually launching.

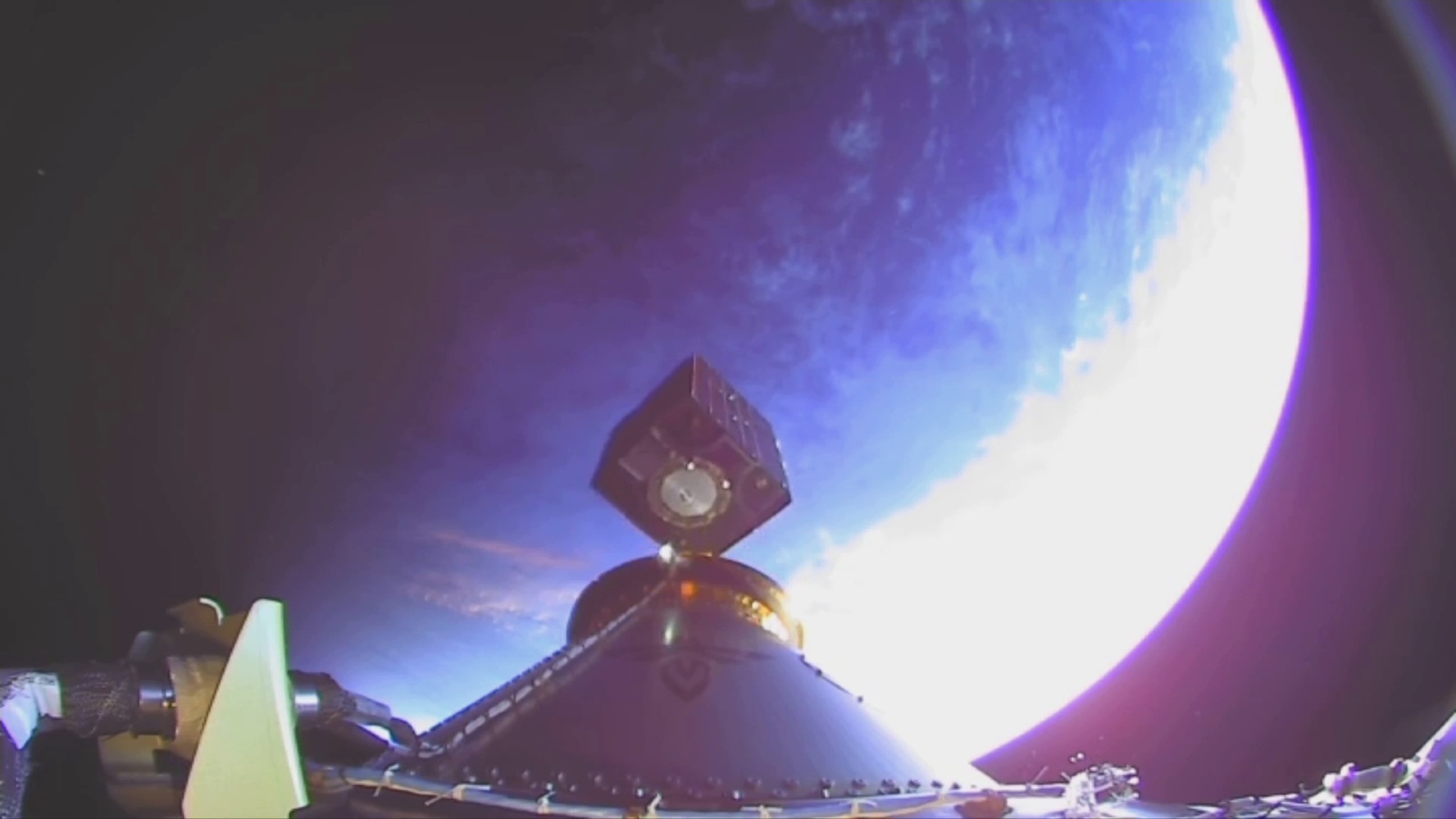

Firefly Aerospace, a company contracted by Space Force, launched one of its Alpha rockets from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California on Sept. 14 at 10:28 p.m. local time, Live Science's sister site Space.com reported. The launch was not publicized or live-streamed, making it a complete surprise to the space exploration community.

The rocket was carrying Space Force's Victus Nox satellite (Latin for "conquer the night"), which will run a "space domain awareness" mission to help Space Force keep tabs on what is happening in the orbital environment.

The surprise rocket initially caught people's eye after creating an enormous exhaust plume that could be seen from more than 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) away. But after the plume dissipated, a faint red glow remained in the sky, which is a telltale sign that the rocket created a hole in the ionosphere — the part of Earth's atmosphere where gases are ionized, which stretches between 50 and 400 miles (80 and 645 km) above Earth's surface — Spaceweather.com reported.

Related: Environmental groups sue US government over explosive SpaceX rocket launch

This is not the first "ionospheric hole" observed this year. In July, the launch of a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket created an enormous blood-red patch above Arizona that could be seen for hundreds of miles.

Rockets create ionospheric holes when fuel from their second stages burns in the middle part of the ionosphere, between 125 and 185 miles (200 and 300 km) above Earth's surface, Live Science previously reported. At this height, the carbon dioxide and water vapor from the rocket's exhaust cause ionized oxygen atoms to recombine, or form back into normal oxygen molecules. This process excites the molecules and leads them to emit energy in the form of light. This is similar to how auroras form, except the dancing lights are caused by solar radiation heating up gases rather than their recombination.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The holes pose no threat to people on Earth's surface and naturally close up within a few hours as the recombined gases get re-ionized.

Firefly Aerospace was awarded the Victus Nox contract in October 2022 but was told that it would have to launch the satellite at an unknown point in the future with less than 24 hours' warning. To accomplish this, the launch team had to update the rocket's trajectory software, encapsulate the satellite, get the satellite to the launch pad, place it in the rocket and go through the final checks within that time, according to a company statement. Even then, bad weather meant they had to launch later than planned.

The aim of the mission was to "demonstrate the United States' ability to rapidly place an asset in orbit when and where we need it, ensuring we can augment our space capabilities with very little notice," Lt. Col. MacKenzie Birchenough, an officer with Space Force's Space Systems Command, said last year when the mission was first announced.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus