See green comet Nishimura's tail get whipped away by powerful solar storm as it slingshots around the sun

After surviving its closest approach to the sun, Comet Nishimura was buffeted by a possible coronal mass ejection that briefly blew its tail away. The rare event was captured by a NASA spacecraft.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The recently discovered green comet Nishimura has been body slammed by a potential coronal mass ejection (CME) after surviving a close encounter with the sun. The unexpected collision, which briefly blew away the comet's tail, was caught on camera by a NASA spacecraft.

In footage captured by NASA's Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO-A) spacecraft, the plasma plume slammed into Nishimura and "jostled around" the comet's tail — the trailing stream of dust and gas that was blown off the comet by the sun — before completely pinching it off, Karl Battams, an astrophysicist at the United States Naval Research Laboratory who created the video of the event (shown above), told Live Science in an email.

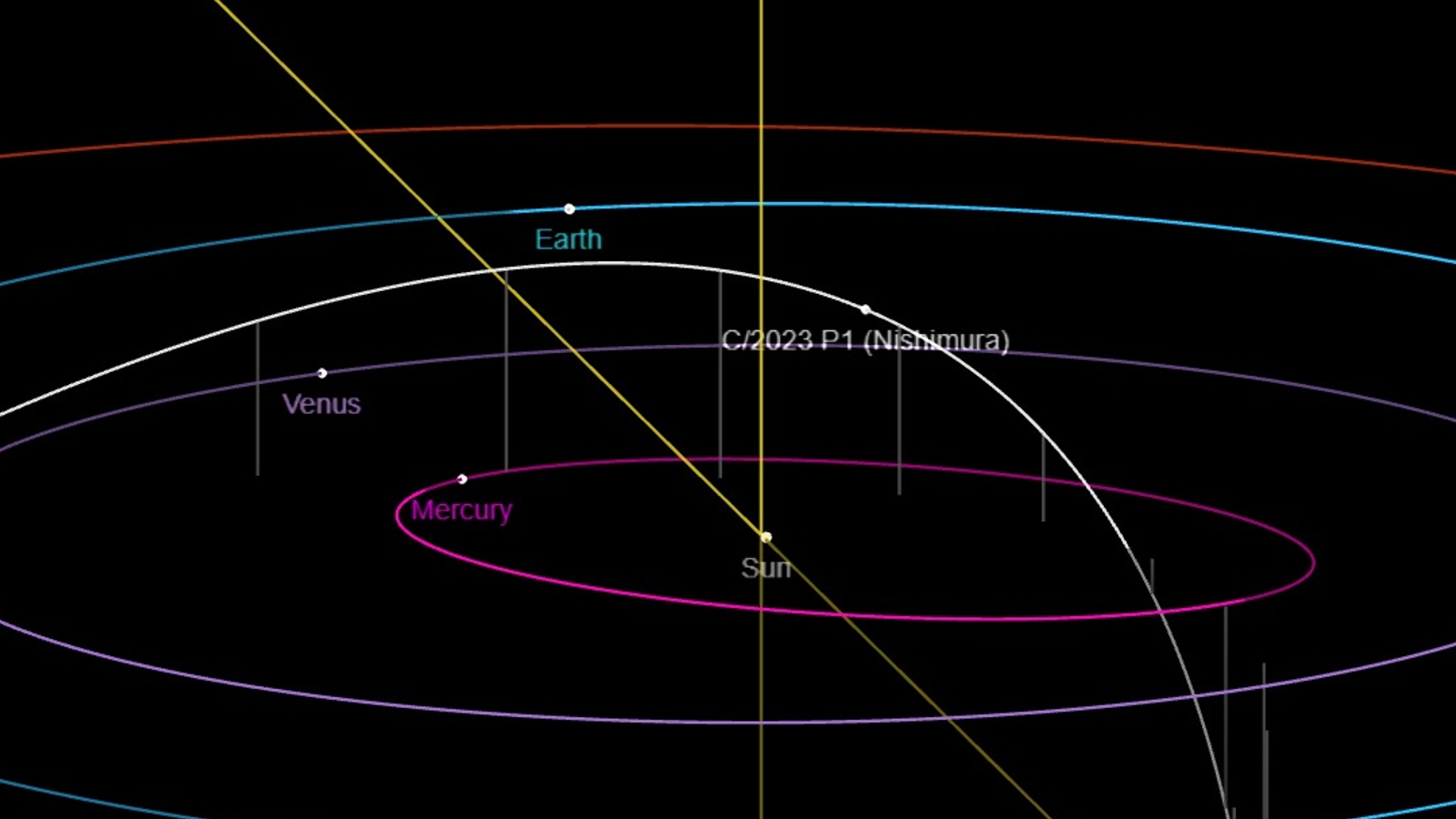

Comet Nishimura, also known as C/2023 P1, was first spotted falling rapidly toward the sun on Aug. 12 by amateur Japanese astronomer Hideo Nishimura. Its steep trajectory initially hinted that it could be an interstellar object, like 'Oumuamua or Comet 2I/Borisov, that would leave the solar system after it slingshotted around the sun. However, follow-up observations revealed that the comet originated from the Oort Cloud — a reservoir of comets and other icy objects beyond the orbit of Neptune — and has a highly elliptical orbit that brings it into the inner solar system roughly every 430 years.

On Sept. 12, Comet Nishimura reached its closest point to Earth when it passed within 78 million miles (125 million kilometers) of our planet, or roughly 500 times the average distance between Earth and the moon. In the days leading up to this, the comet became clearly visible near the horizon shortly before sunrise and shortly after sunset, which led to some stunning photos of the icy object streaking across the night sky. In some of these photos, Nishimura gave off a green glow due to a high concentration of dicarbon in the cloud of gas and dust, known as a coma, that surrounds its rocky core.

On Sept. 17, the comet reached its minimum distance from the sun, known as perihelion, as it slingshotted around our home star at a distance of 20.5 million miles (33 million km). This type of close encounter can often cause comets to burn up and break apart. But astronomers soon discovered that Nishimura had survived the superheated, high-G maneuver.

Related: City-size comet headed toward Earth 'grows horns' after massive volcanic eruption

As Nishimura began to fly away from the sun it passed in front of STEREO-A, which kept a close eye on the escaping comet. Then on Sept. 22, the sun belched out an enormous wave of plasma, or ionized gas, which either came from a strong burst of solar wind or a CME, Spaceweather.com reported. The CME blasted off the comet's tail in what's called a disconnection event. The effect is only temporary and "entirely harmless" for the comet, Battams said. After a disconnection event, a comet's tail will regrow as more dust and gas is blown from the comet.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This is not the first time Nishimura has lost its tail. Earlier in September, a pair of CMEs slammed into the comet, causing at least one disconnection event, Live Science's sister site Space.com reported. But despite being constantly bombarded by the sun, the comet has been surprisingly "well-behaved" and remains on its original trajectory, Battams said.

For most people, the comet is unlikely to become visible to the naked eye again before heading back into the Oort Cloud. But, unless it "randomly breaks apart" over the next few weeks and months (which is possible), "it seems there’s a decent chance that folks a few centuries from now will get to enjoy it again next time it swings through the neighborhood," Battams said.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus