Green comet Nishimura survives its superheated slingshot around the sun. Will we get another chance to see it?

Comet Nishimura, which was only discovered in August, has survived its closest approach to the sun and will brighten over the next week. But is it still visible from Earth?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A recently discovered green comet, named Nishimura, has survived its close encounter with the sun and begun its journey back into the outer reaches of the solar system. Once gone, it won't return for around 430 years. But it could be visible over the next few weeks, depending on where you live.

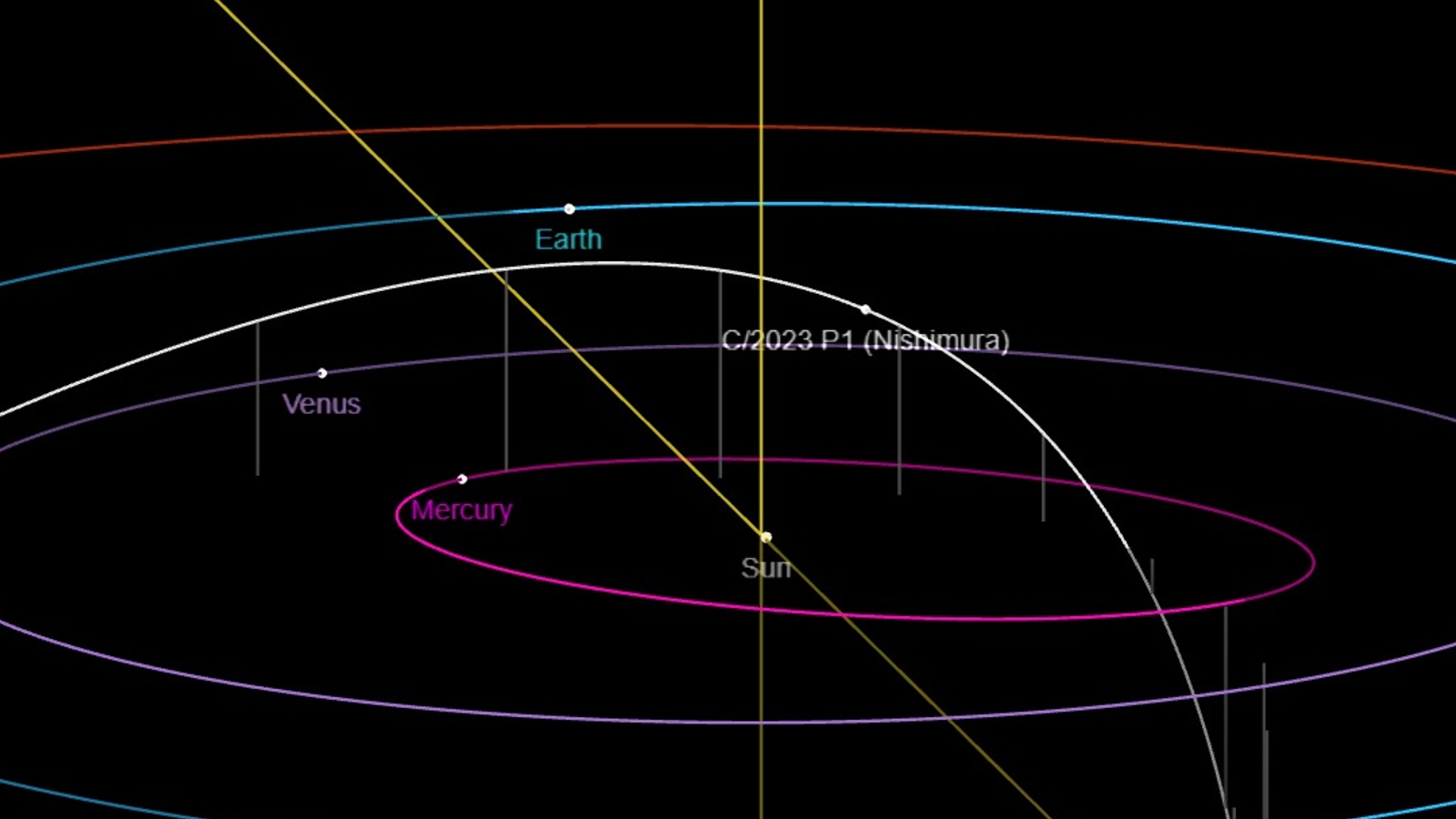

Comet Nishimura, also known as C/2023 P1, was first spotted falling rapidly toward the sun on Aug. 12 by amateur Japanese astronomer Hideo Nishimura. The icy object has a green glow caused by high levels of dicarbon in its coma — the cloud of gas and dust that surrounds its solid core.

The comet's trajectory initially suggested that it may have been a potential interstellar object, like 'Oumuamua or Comet 2I/Borisov, that was making its first and final trip through the solar system. However, further observation revealed that it actually has an extremely elliptical orbit, which only brings it into the inner solar system every 430 years before slingshotting around the sun and returning to the Oort Cloud — a reservoir of comets and other icy objects beyond the orbit of Neptune.

On Sept. 12, Comet Nishimura made its closest approach to Earth, passing within 78 million miles (125 million kilometers) of the planet, or roughly 500 times the average distance between Earth and the moon. And on Sept. 17, the comet reached perihelion, or the closest point to the sun, when it dipped within 20.5 million miles (33 million km) of our home star.

Related: City-size comet headed toward Earth 'grows horns' after massive volcanic eruption

Getting so close to the sun can be deadly for comets. The increased heat and radiation can cause them to shatter into many smaller pieces. However, Nishimura appears to have emerged mostly unscathed, according to Spaceweather.com.

As Comet Nishimura moves away from the sun and slightly toward Earth it will become fractionally brighter as more light reflects off its coma, which will have grown slightly from its brush with the sun. But this doesn't necessarily mean we will be able to see it any better.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The comet's trajectory and close proximity to the sun only make it visible near the horizon shortly before sunrise or shortly after sunset. It's also much dimmer than it was on its approach to Earth, when it became clearly visible to the naked eye. As a result, you need a strong telescope or specialized astrophotography equipment to catch a decent sight of the comet.

Astrophotographer Petr Horalek captured a blurry shot of the comet (shown below) on Sept. 17 above Slovakia's Mount Lysa, shortly after the sun reached its closest point to the sun. However, he could not see the comet without his equipment, he told Live Science in an email.

However, if you live in Australia, your chances of being able to catch a glimpse of Nishimura with your own eyes are slightly better over the next week. Between Sept. 20 and Sept. 27, the comet will set around one hour after the sun, the furthest distance away from our home star over the next few weeks. And the increased separation will make it appear brighter to observers in this part of the world, Live Science's sister site Space.com reported.

However, the rest of us may still get another chance to spot the comet later in the year — or perhaps some scattered bits of it.

Some experts believe Nishimura could potentially be the source of the annual Sigma-Hydrids meteor shower, a minor shower that peaks annually in early December, according to the astronomy news site EarthSky. If this is the case, then Nishimura’s passing could cause this year's shower to be much more active and visually stunning than normal. Further observations in December could help confirm or disprove this theory.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus