City-size comet headed toward Earth 'grows horns' after massive volcanic eruption

The exploding comet, known as 12P/Pons–Brooks, is currently approaching its closest point to Earth during its 71-year orbit through the solar system.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

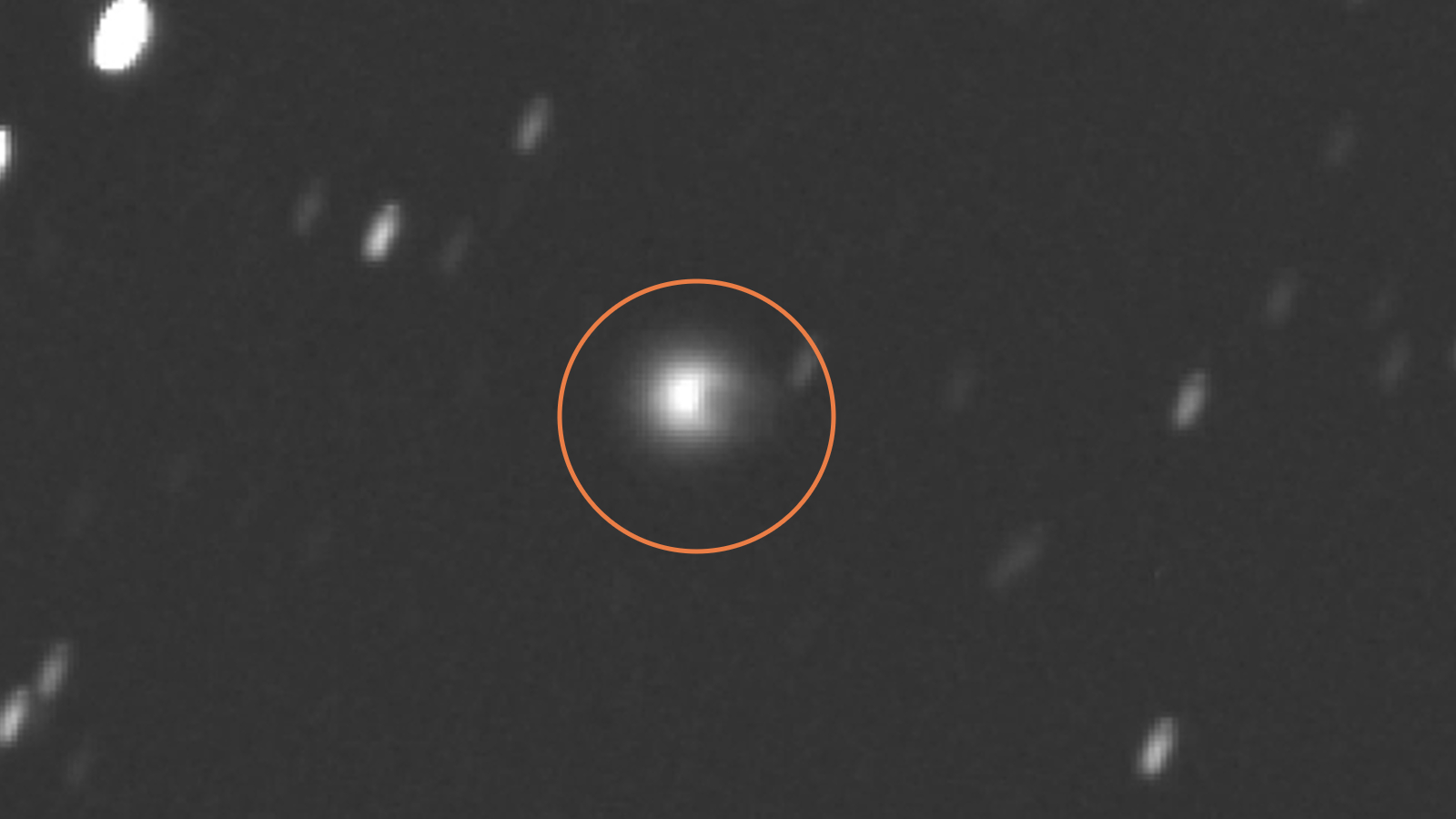

An unusual volcanic comet flying toward the sun appears to have "grown horns" after it exploded, causing it to shine like a small star and shower supercold "magma" into space. It is the first time this comet has been seen erupting in almost 70 years.

The comet, named 12P/Pons-Brooks (12P), is a cryovolcanic — or cold volcano — comet. Like all other comets, the icy object is made up of a solid nucleus, filled with a mix of ice, dust and gas, and is surrounded by a fuzzy cloud of gas called a coma, which leaks out of the comet's interior. But unlike most other comets, the gas and ice inside 12P's nucleus build up so much that the celestial object can violently explode, shooting out its frosty guts, known as cryomagma, through large cracks in the nucleus's shell.

On July 20, multiple astronomers detected a major outburst from the comet, which suddenly became around 100 times brighter than it usually appears, Spaceweather.com reported. This increase in brightness occurred when the comet's coma suddenly swelled up with gas and ice crystals released from the comet's interior, allowing it to reflect more sunlight back to Earth.

As of July 26, the comet's coma had grown more than 7,000 times wider than its nucleus, which has an estimated diameter of around 10.5 miles (17 km), Richard Miles, an astronomer with the British Astronomical Association who studies cryovolcanic comets, told Live Science in an email.

But interestingly, an irregularity in the shape of the expanded coma makes the comet look as though it has sprouted horns. Other experts have also likened the deformed comet to the Millennium Falcon, one of the iconic spaceships from Star Wars, Spaceweather.com reported.

Related: Gigantic 'alien' comet spotted heading straight for the sun

The unusual shape of the comet's coma is likely due to an irregularity in the shape of 12P's nucleus, Miles said. The outflowing gas was likely partially obstructed by an out-sticking lobe on the nucleus, which created a "notch" in the expanded coma. As the gas continued to move away from the comet and grow, the notch, or "shadow," became more noticeable, he added. But the expanded coma will eventually disappear as the gas and ice becomes too dispersed to reflect sunlight.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This is the first major eruption detected from 12P in 69 years, Miles said, mainly because its orbit takes it too far away from Earth for its outbursts to be noticed.

12P has one of the longest known orbital periods of any comet. It takes around 71 years for the floating volcano to fully orbit the sun, during which time it is catapulted out to the farthest reaches of the solar system. The comet is due to reach its closest point to the sun on April 21, 2024 and make its closest approach to Earth on June 2, 2024, at which point it will be visible in the night sky, Spaceweather.com reported. Earthlings could, therefore, get a front-row seat to more eruptions over the next few years.

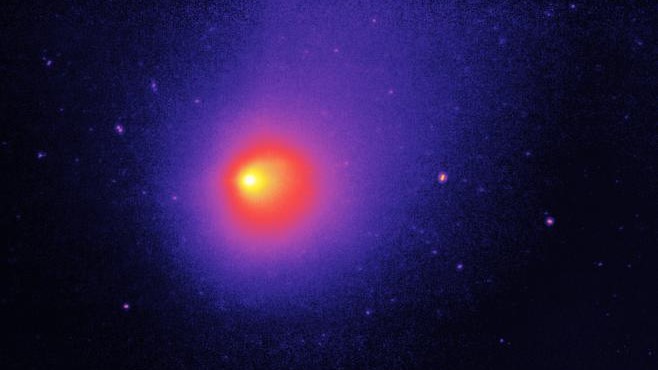

But 12P is not the only volcanic comet researchers have their eyes on right now. Over the past few years, there have been several notable eruptions from 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann (29P) — the most volatile volcanic comet in the solar system.

In December 2022, astronomers witnessed the largest eruption from 29P in around 12 years, which sprayed around 1 million tons of cryomagma into space. And in April this year, for the first time ever, scientists were able to accurately predict one of 29P's eruptions before it actually happened, thanks to a slight increase in brightness, which suggested more gas was leaking out of the comet's nucleus as it prepared to pop.

Editor's note: This story was updated on Tuesday (Nov. 7) at 12:10 p.m. ET to correct an error about comet 12P's diameter.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus