Rare embryo from dinosaur age was laid by human-size turtle

The eggshell was incredibly thick.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

About 90 million years ago, a giant turtle in what is now central China laid a clutch of tennis ball-size eggs with extremely thick eggshells. One egg never hatched, and it remained undisturbed for tens of millions of years, preserving the delicate bones of the embryonic turtle within it.

In 2018, a farmer discovered the egg and donated it to a university. Now, a new analysis of this egg and its rare embryo marks the first time that scientists have been able to identify the species of a dinosaur-age embryonic turtle.

This specimen also sheds light on why its species, the terrestrial turtle Yuchelys nanyangensis, went extinct 66 million years ago at the end of the Cretaceous period, when the dinosaur-killing asteroid struck Earth. The thick eggshell allowed water to penetrate through, so clutches of eggs were likely buried in nests deep underground in moist soil to keep them from drying out in the arid environment of central China during the late Cretaceous, the researchers said.

While these turtles' unique terrestrial lifestyle, thick eggs and underground nesting strategy may have served them well during the Cretaceous, it's possible that these specialized turtles couldn't adapt to the cooler "climatic and environmental changes following the end-Cretaceous mass extinction," study co-researcher Darla Zelenitsky, an associate professor of paleobiology at the University of Calgary in Canada, told Live Science.

Related: Photos: These animals used to be giant

Egg-cellent discovery

The farmer discovered the egg in Henan province, a region famous for the thousands of dinosaur eggs people have found there over the past 30 years, Zelenitsky said. But in comparison with dinosaur eggs, turtle eggs — especially those with preserved embryos — rarely fossilize because they're so small and fragile, she said.

The Y. nanyangensis egg, however, persisted because it's a tank of an egg.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

At 2.1 by 2.3 inches (5.4 by 5.9 centimeters) in size, the nearly spherical egg is just a bit smaller than a tennis ball. That's larger than the eggs of most living turtles, and just a tad smaller than the eggs of Galápagos tortoises, Zelenitsky said.

The eggshell's 0.07 inch (1.8 millimeters) thickness is also remarkable. To put that in perspective, that's four times thicker than a Galápagos tortoise eggshell, and six times thicker than a chicken eggshell, which has an average thickness of 0.01 inch (0.3 mm). Larger eggs tend to be thicker, like the 0.08-inch-thick (2 mm) ostrich eggshell, but "this egg is much smaller than an ostrich egg," which average about 6 inches (15 cm) in length, Zelenitsky said.

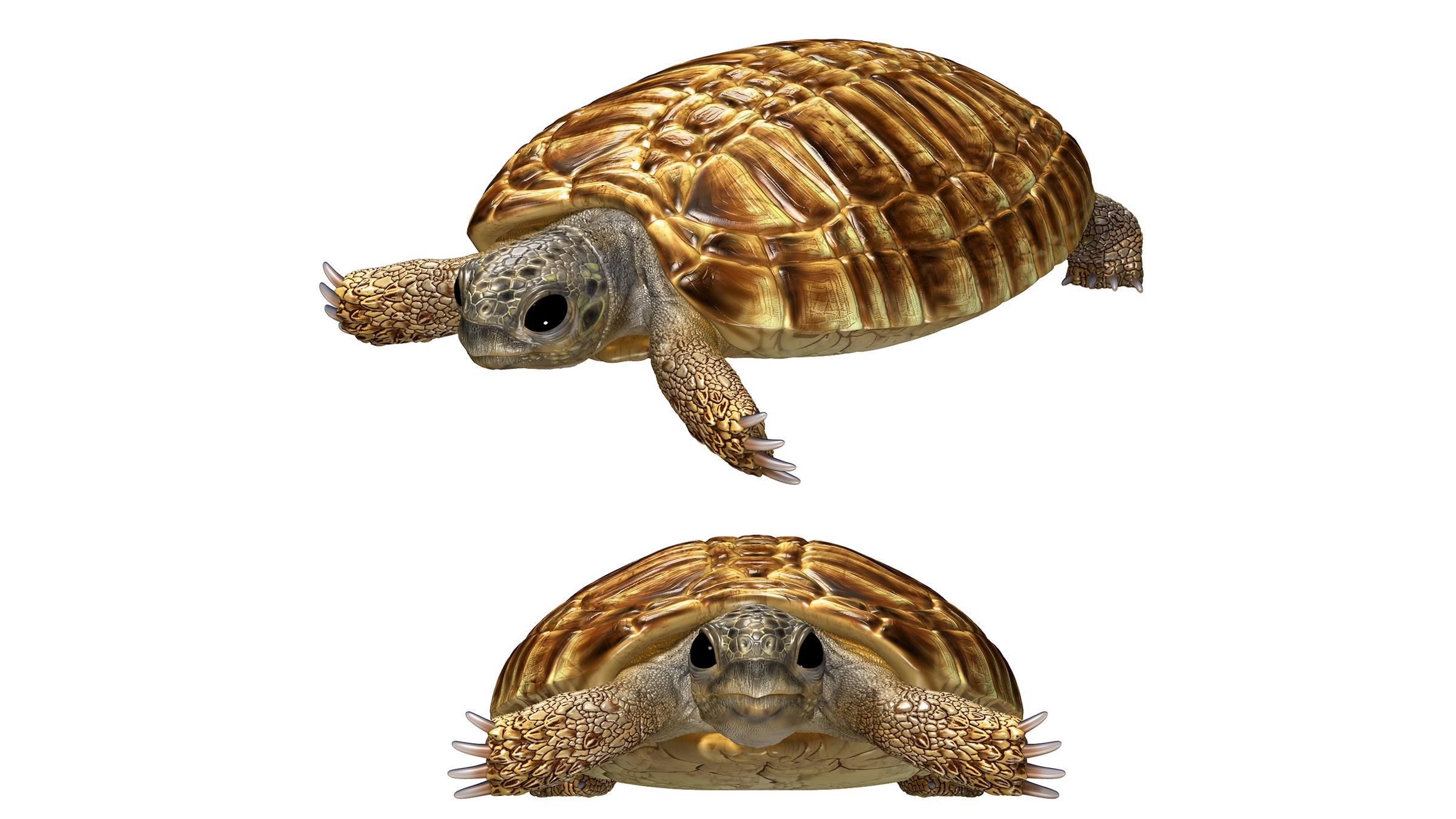

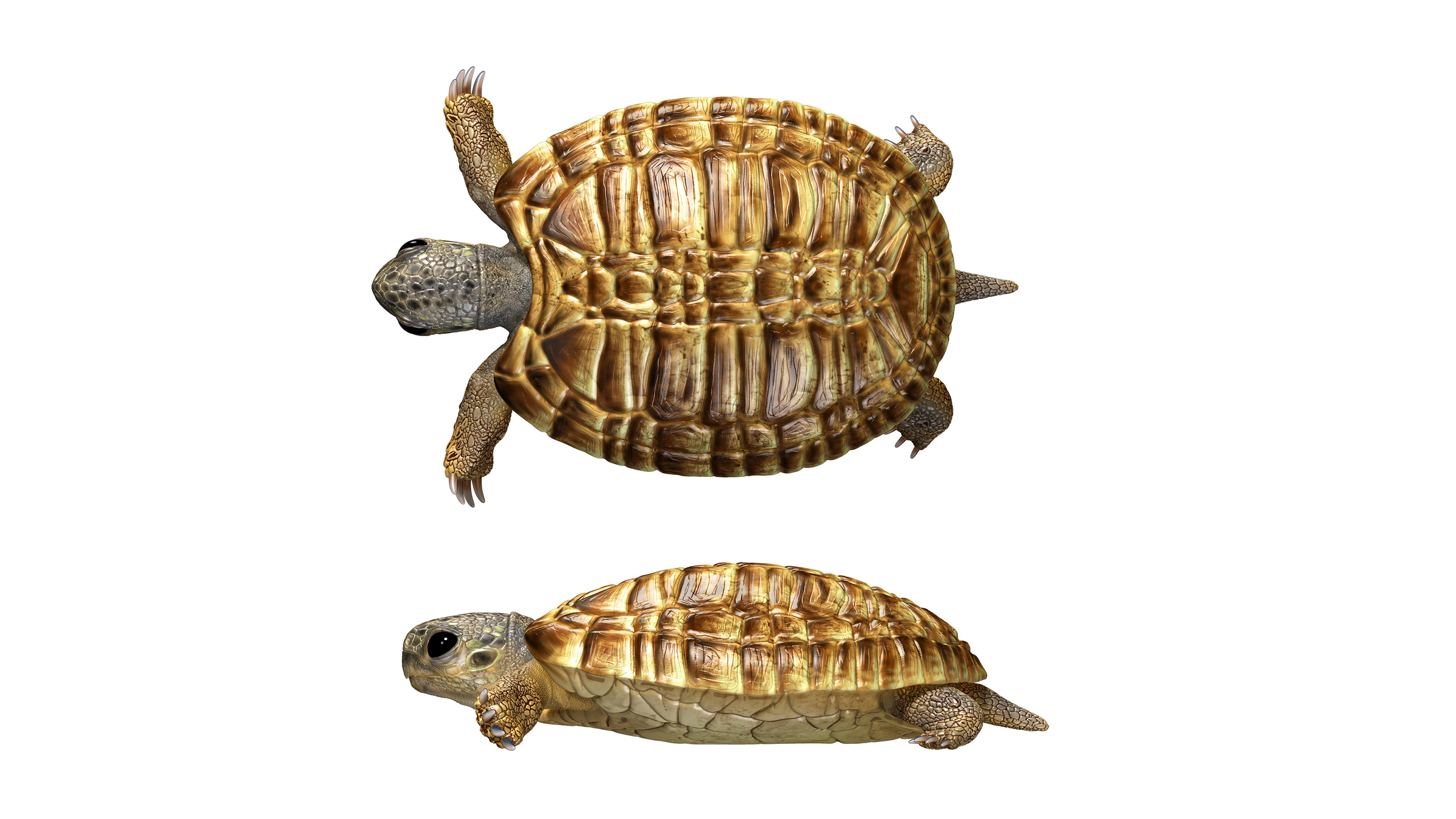

An equation that uses egg size to predict the length of the carapace, or the top part of the turtle's shell, revealed that this thick egg was likely laid by a turtle with a 5.3-foot-long (1.6 meters) carapace, the researchers found. That measurement doesn't include the length of the neck or head, so the mother turtle was easily as long as some humans are tall.

Doomed egg

The researchers used a micro-CT scan to create virtual 3D images of the egg and its embryo. By comparing these images with a distantly related living turtle species, it appears that the embryo was nearly 85% developed, the researchers found.

Part of the eggshell is broken, Zelenitsky noted, so "maybe it tried to hatch," but failed. Apparently, it wasn't the only embryonic turtle that didn't make it; two previously discovered thick-shelled egg clutches from Henan province that date to the Cretaceous — one with 30 eggs and another with 15 eggs — likely also belong to this turtle's now-extinct family, known as Nanhsiungchelyid, the researchers said.

Turtles in this family — relatives of today's river turtles — were very flat and evolved to live entirely on land, which was unique during that time, Zelenitsky said.

The study of the newfound egg is special for its virtual 3D analysis of the embryo, which helped lead to its species diagnosis, said Walter Joyce, a professor of paleontology at the University of Fribourg in Switzerland, who was not involved in the study. Furthermore, this study offers evidence that Nanhsiungchelyid turtles were "adapted to living in harsh, terrestrial environments, but laid their large, thick-shelled eggs in covered nests in moist soil," Joyce told Live Science in an email.

The study will be published online Wednesday (Aug. 18) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus