Gulf Stream weakening now 99% certain, and ramifications will be global

A new analysis has concluded that the Gulf Stream is definitely slowing, but whether it's due to climate change is hard to tell.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The Gulf Stream is almost certainly weakening, a new study has confirmed.

The flow of warm water through the Florida Straits has slowed by 4% over the past four decades, with grave implications for the world's climate.

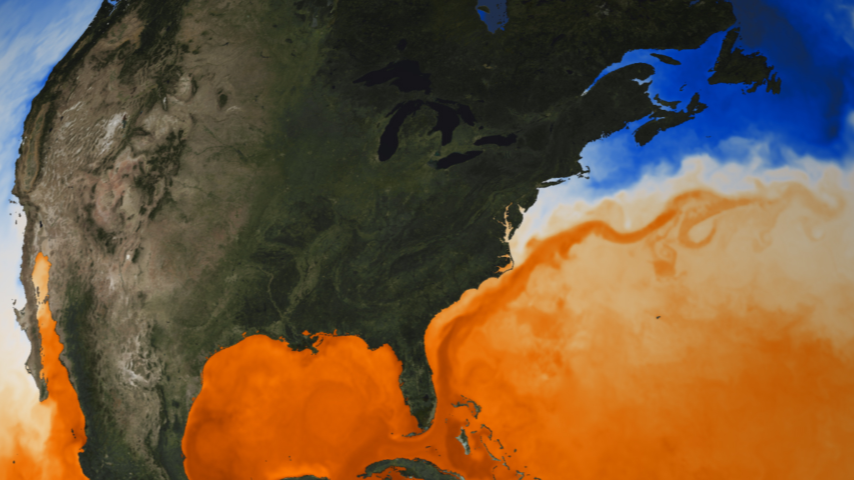

The ocean current starts near Florida and threads a belt of warm water along the U.S. East Coast and Canada before crossing the Atlantic to Europe. The heat it transports is essential for maintaining temperate conditions and regulating sea levels.

But this stream is slowing down, researchers wrote in a study published Sept. 25 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

"This is the strongest, most definitive evidence we have of the weakening of this climatically-relevant ocean current," lead-author Christopher Piecuch, a physical oceanographer at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, said in a statement.

The Gulf Stream is just a small component of the thermohaline circulation — a global conveyor belt of ocean currents that moves oxygen, nutrients, carbon and heat around the planet, while also helping to control sea levels and hurricane activity.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Beginning in Caribbean before flowing out into the Atlantic through the Florida Straits, the Gulf Stream brings warmer southerly waters (which are saltier and denser) northward to cool and sink in the North Atlantic. After dropping deep beneath the ocean and releasing its heat into the atmosphere, the water slowly drifts southward, where it heats up again and the cycle repeats.

This process is vital for maintaining temperatures and sea levels across the U.S. East Coast — whose waters are kept up to 5 feet (1.5 meters) lower than water further offshore by the sweeping motion of the current.

As Earth’s climate warms, an enormous influx of cold, fresh water from melting ice sheets is spilling into oceans, possibly causing the Gulf Stream to slow or even veer toward outright collapse, according to scientists. But due to the scale and complexity of the system, this is hard to prove.

To find definitive evidence that the stream is slowing, scientists analyzed data spanning 40 years from three separate sources — undersea cables, satellite altimetry and observations made on site — to observe the motions of the current around the Florida Straits.

Their statistical analysis revealed that the current had slowed by 4%, with just a 1% chance of their measurement being a fluke caused by random fluctuations.

At first glance, a 4% shift may seem like a miniscule change, but "the worry is that's just the slow start," Helen Czerski, an oceanographer at University College London (UCL) who was not involved in the study, told Live Science.

Related: Read about the planet's engine in an interview with Helen Czerski

"It's like those early days of COVID. People were like: 'Oh, there's only 60 cases. We don't care about this,'" she added. "There's only 60 cases, yeah, but yesterday there were 30 and the day before that there were 15. If you just think a week ahead, we've got a problem."

To find definitive proof that climate change is the culprit, scientists will need to tease apart the differences between the natural variability of the ocean systems and the impact made by global heating — a tricky task given the relatively short time that humans have been directly measuring the ocean flows in detail.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based writer and editor at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus