Did Leonardo da Vinci's 'quick eye' help him capture Mona Lisa's fleeting smile?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The famed Renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci may have been blessed with the same "quick eye" that may give top tennis and baseball players an edge. In Leonardo's case, this super-vision may have enabled him to see and capture fleeting moments in his paintings — such as the enigmatic half-smile of the Mona Lisa.

This ability to see details in even the fastest-moving or fleeting phenomenon may be a result of a higher flicker fusion frequency, said David Thaler, a geneticist at the University of Basel in Switzerland. He added that the trait could explain how some baseball players can spot the seams of the ball in flight, for example, or how some tennis stars can react to a super-fast ball.

For Leonardo, a high flicker fusion frequency could explain how he was able to describe the changes in the shape of falling drops of water, and recognize the fleeting expressions seen in many of his paintings.

In the case of the Mona Lisa, "what I'm proposing is that Leonardo caught a moment of breaking into a smile," he said. "It is not a posed smile held steady, but that passing instant when the smile is in the act of becoming."

Related: In Photos: Leonardo Da Vinci's 'Mona Lisa'

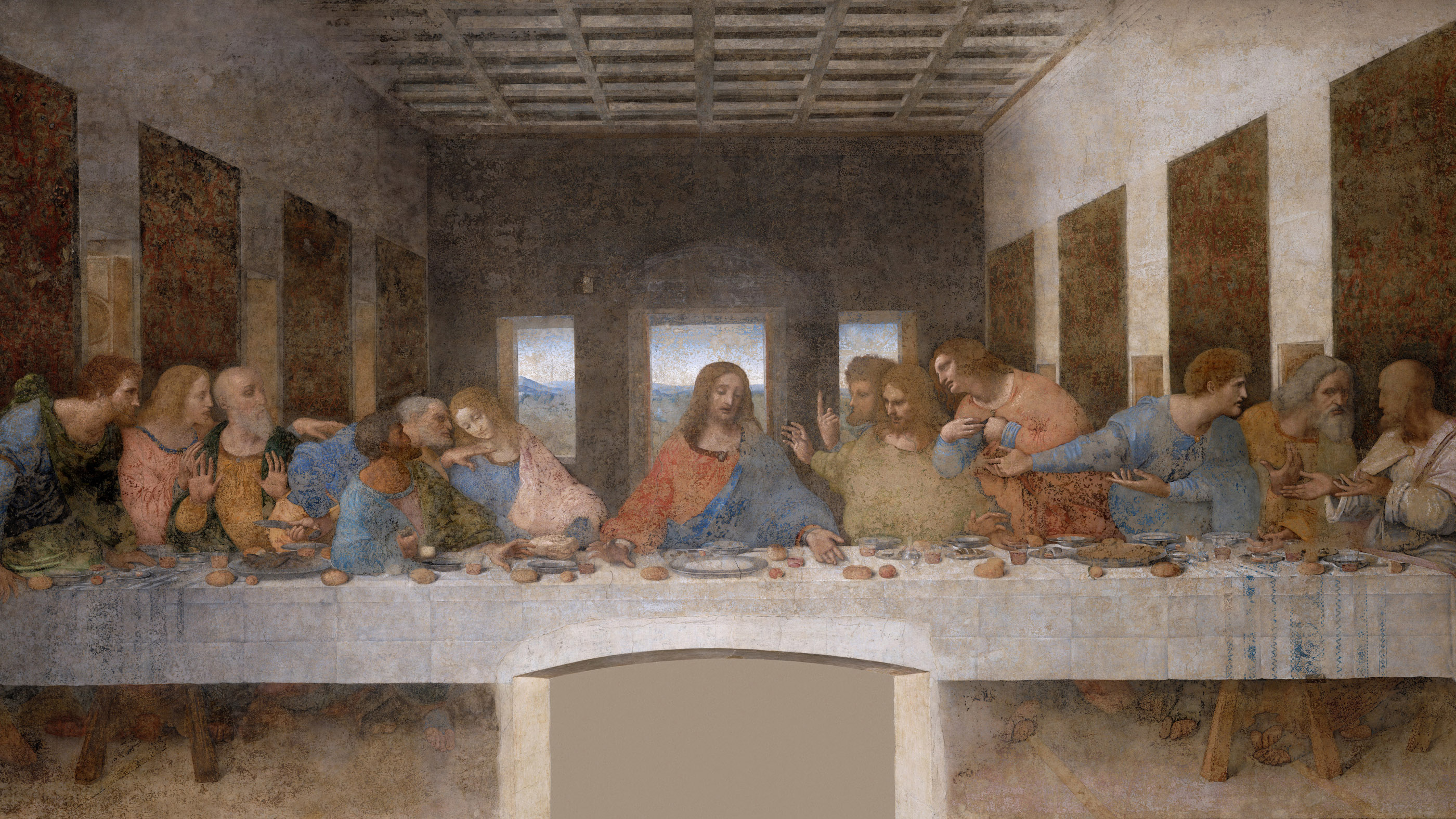

Leonardo's painting of The Last Supper — a fresco on the wall of a church in Milan — also captures the fleeting expressions of the apostles, supposedly after Jesus Christ told them that "one of you here will betray me," Thaler said.

What is a quick eye?

Thaler was first inspired to investigate Leonardo's vision by a comment the artist wrote in one of his notebooks on the flight of dragonflies.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The dragonfly flies with four wings, and when those in front are raised those behind are lowered," Leonardo wrote.

"I thought, 'That's cool, I'm going to see myself,'" Thaler said. "It was summer and there were dragonflies around."

But "I looked as hard and carefully as I could, but to me the wings on flying dragonflies were always a blur," he said. His friends, too, could not discern the flying motion. "I started to read and think more seriously about what it means to have a fast eye."

Related: 5 things you probably didn't know about Leonardo Da Vinci

Thaler's research shows that a dragonfly's back wings are out of sync with the front wings by about a hundredth of a second.The comment in his notebooks suggests that Leonardo could see that hundredth of a second difference, which corresponds to a flicker fusion frequency of 100 hertz, or 100 times a second — roughly twice the flicker fusion frequency of most humans, he said.Thaler believes that the "quick eye" of Leonardo and some modern sports stars could have a genetic basis, perhaps in the genes that govern the development of the potassium channels in the cells of the retina.

It's been shown that several nonhuman species, such as insects, have marked genetic differences in their retinas that enables them to see much faster motions — and differences in the development of cells in the retina might cause differences in the vision of humans too, he said.

Artistic vision

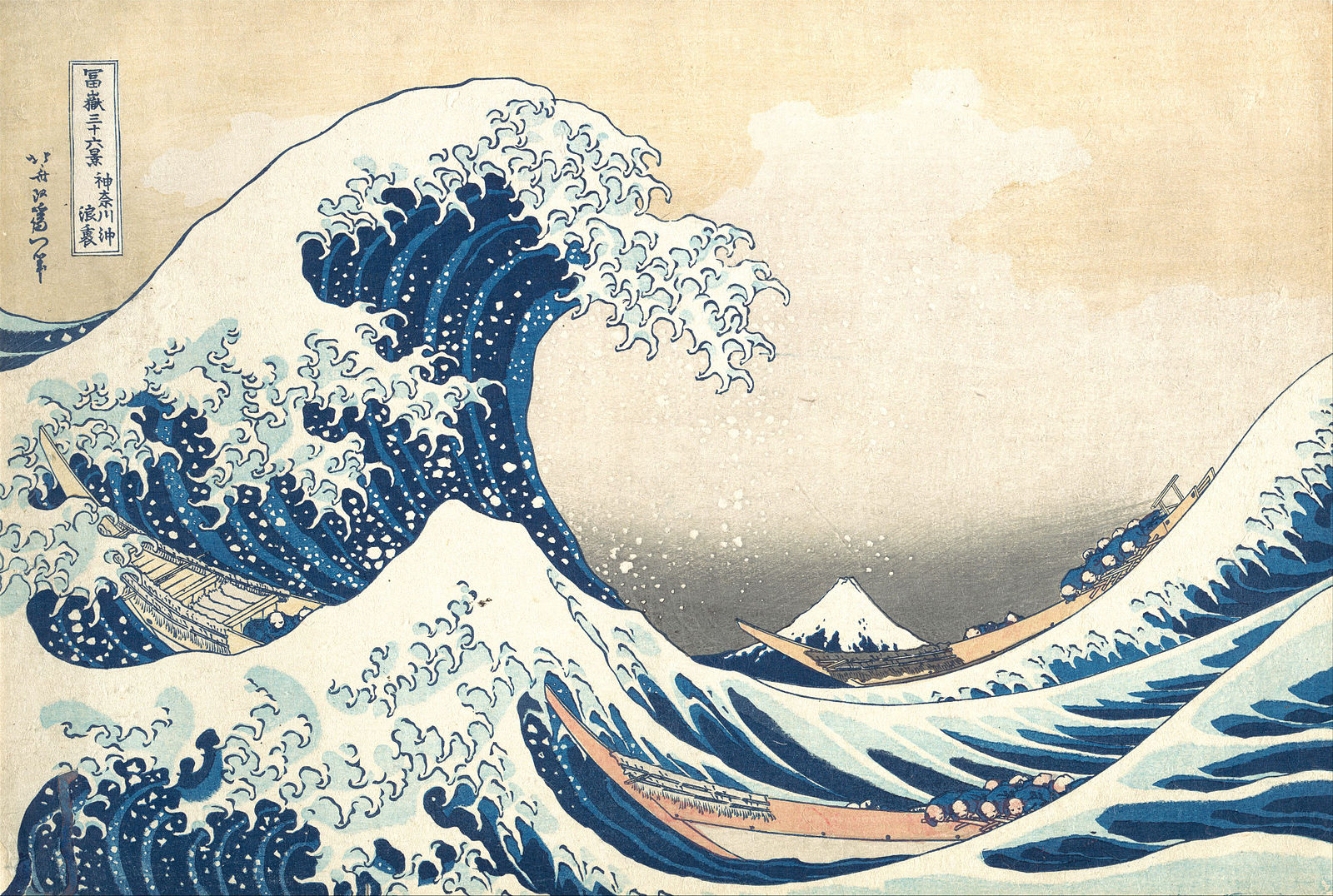

Other famous artists have shown the same ability to capture fleeting moments in their work, such as the Japanese printmaker Katsushika Hokusai, who created the iconic woodcut "Under the Wave of Kanagawa" — also known as "The Great Wave", Thaler said.

Hokusai, who lived from 1760 until 1849, also made a woodcut of a dragonfly in flight that shows the correct motion of the insect's wings. "At least one other artist seems to have had such a fast and accurate eye," Thaler said.

Related: Flying machines? 5 Da Vinci designs that were ahead of their time

Thaler said a DNA sample from Leonardo's might be able to show if his quick eye was based on the genes that regulated the development of his retinas, or if it came about from training and close observation.

His new research has been published by the Leonardo Da Vinci DNA Project, which hopes one day to recover Leonardo's genetic material from his paintings. "If they do manage to get the sequence, that's the part I would be interested in," Thaler said.

Thaler also sees signs of Leonardo's sensitivity to visual phenomena — perhaps including his "quick eye" — in his use of "sfumato" in his paintings, an artistic technique that details or blurs aspects of a painting in order to bring them in and out of focus.

Whole images are constructed by the brain from a series of much smaller, instantaneous images, each of which had full clarity only in the small foveal region of the retina, he said. Ordinary people, however, don't perceive this mental stitching process and visualize a scene as a cohesive whole with one central focus.

In contrast, Leonardo's expert use of sfumato — in the Mona Lisa, for example, and in his Salvator Mundi — could derive from an ability to see these instantaneous images and recognize their partial focus, he said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus