1st-of-its-kind Parkinson's treatment may slow aggressive disease, trial hints

A new antibody drug for Parkinson's disease appears to slow the progression of its movement-related symptoms, at least in some patients.

A first-of-its kind antibody treatment may slow the progression of movement problems in some people with Parkinson's disease (PD), early clinical trial data suggest.

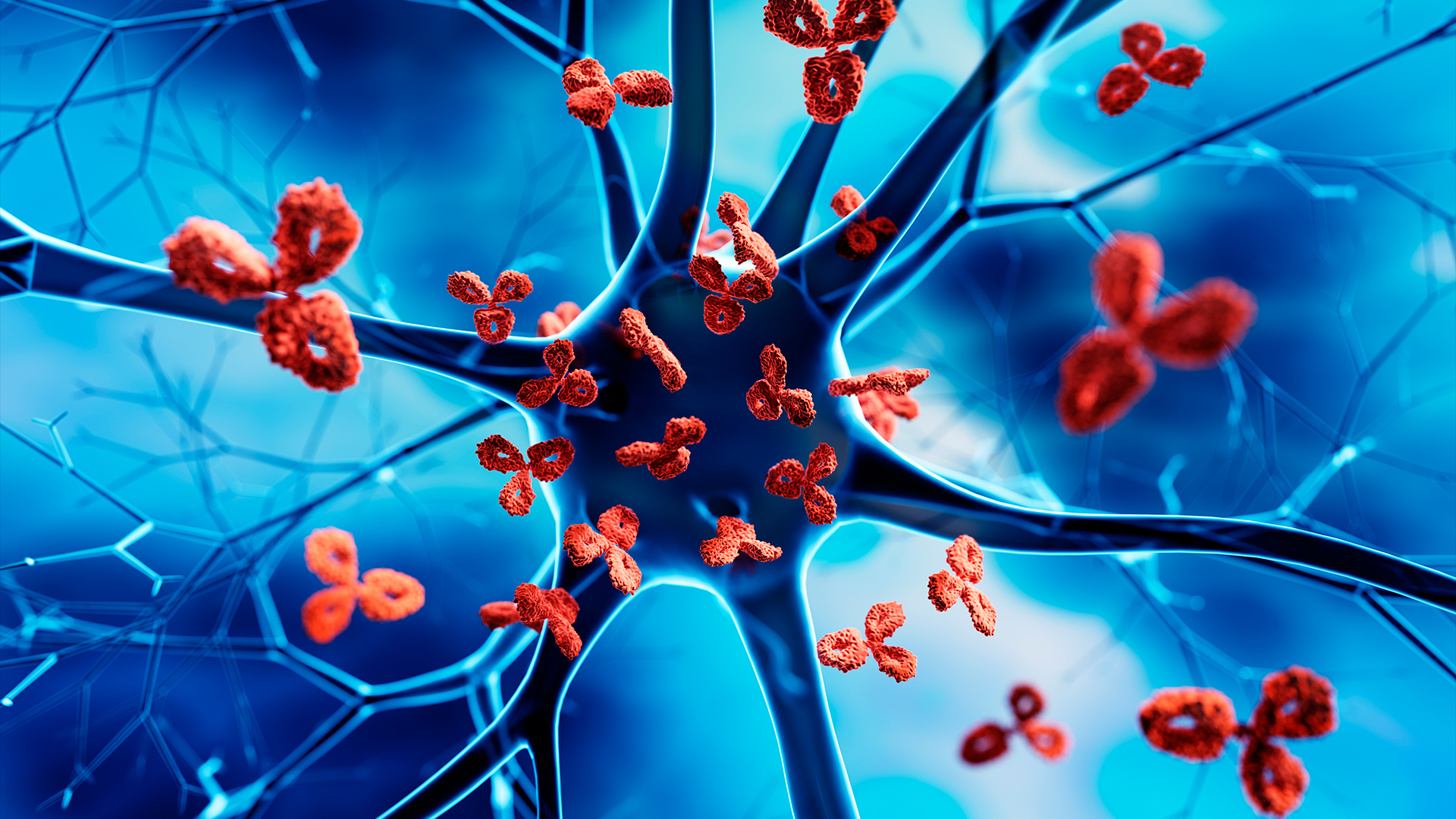

Current treatments for PD only ease its symptoms; they don't address its underlying causes in the brain. Now, the new antibody, called prasinezumab, has shown promise in treating one cause of the disease and thus in slowing down its movement symptoms, such as tremors and stiffness.

One of the main drivers of PD is thought to be the accumulation of an abnormal version of a protein called alpha synuclein in the brain. Prasinezumab targets and helps break down these protein clumps, with the goal of slowing the disease.

Now, there's evidence that prasinezumab may work, at least for some people. An analysis from an ongoing, midstage clinical trial suggests prasinezumab may slow the signs of motor dysfunction in people with rapidly progressing forms of PD. The results were published Monday (April 15) in the journal Nature Medicine.

Related: Gene variant guards against Parkinson's and could lead to therapies

The analysis took a closer look at 316 participants from the clinical trial. An earlier phase of the research had tested the effect of prasinezumab on PD progression in these people but did not find that it had a meaningful effect, overall. However, the participants' symptoms progressed at widely different speeds.

The researchers speculated that the rate of disease progression in different people might have skewed the results, masking benefits that the therapy may have offered people with faster progressing disease. So, they took a second look at these individuals with aggressive disease, who made up about one-quarter of the overall group, and compared those treated with prasinezumab for a year to those given a placebo.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They used standard tools to measure how quickly the participants' movement symptoms worsened and found that patients treated with prasinezumab fared better than those treated with placebo.

There are several explanations for why the antibody showed a greater effect on participants with rapidly progressing symptoms, Gennaro Pagano, group leader and expert medical director at Roche, told Live Science in an email. (Pagano and several other study authors are employees and shareholders of Roche, the company sponsoring the trial.)

Patients whose PD progresses more quickly may have a larger amount or wider distribution of alpha synuclein clumps in the brain than people with more slowly progressing PD do. This would give the antibody more to break down, thereby boosting the effects of the treatment, Pagano said.

This is a hypothesis, as the researchers didn't directly track the alpha-synuclein levels in people's brains, Vinata Vedam-Mai, a neurology researcher at the University of Florida Health, told New Scientist. Thus, they can't say for sure that the antibody cleared away the protein.

The results could also partly come down to statistics. The effects of the treatment may be more obvious in aggressive disease because it triggered a greater degree of change in the patients, Pagano said.

In addition, the research team used a few criteria to identify people with rapid PD, including their scores on standard Parkinson's tests and whether they took medication to relieve their symptoms. These drugs may have acted together with prasinezumab to have a greater, collective effect on people's movement symptoms, Pagano noted.

Although prasinezumab didn't seem to work for people with slower PD, it may be that a longer trial period is needed to spot changes in these individuals, the researchers noted in their report.

The results seen in people with rapid disease also need to be confirmed. For now, the analysis is "exploratory," especially given the small size of the subgroups, and the trial is still ongoing, Pagano said.

If the work pans out, he said, the hope is that it will lead to a therapy that treats PD, directly, rather than only easing its symptoms.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Sneha Khedkar is a biologist-turned-freelance-science-journalist from India. She holds a master's degree in biochemistry and a bachelor's degree in microbiology and biochemistry. After her master's, she worked as a research fellow for four years, studying stem cell biology. Her articles have been published in Scientific American, Knowable Magazine, and Undark, as well as several Indian platforms such as The Hindu and The Wire Science, among others. Besides writing, she enjoys a good cup of tea, reading novels and practicing yoga.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus