'Excess deaths' tied to COVID have plummeted in America — what does that mean?

Data shows that America's excess death rates have mostly returned to pre-pandemic levels, reflecting the end of the public health crisis, experts say.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

During the worst waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, between 30% and 46% more people in the U.S. were dying each week than would have under typical circumstances. But in the past few months, we've seen this "excess death rate" fall, and now, it's hovering near zero.

Does that mean America has seen the end of the COVID-19 pandemic? And that the coronavirus can now be considered "endemic" to the country? Experts told Live Science that, yes, it's reasonable to declare the pandemic over in the U.S. — but that doesn't mean U.S. residents no longer face any risk of harm from COVID-19.

Related: 'Face blindness' could be rare long COVID symptom, case report hints

What are 'excess deaths'?

Essentially, the excess death rate is the number of actual deaths recorded, of any cause, minus the number of deaths that would have been expected over a given time period, based on historical data.

"[Excess death rate] is always going to be based on mathematical models. It's always going to be flawed," Dr. Shira Doron, chief infection control officer for Tufts Medicine in Massachusetts, told Live Science. She said it's very difficult to establish a baseline for what death rates "should" be, given that past mortality rates may have been shaped by unique public health threats, and the emergence of new medical treatments may now be improving survival rates for different illnesses.

But despite its flaws, "it was a metric that was useful during COVID because of the concern that we may not be capturing all COVID deaths," Doron said. Rather than only relying on death certificates that list "COVID-19" as a primary or contributing cause of death, excess death rates can capture the pandemic's wider impact and help determine the number of people who died both directly and indirectly of the disease.

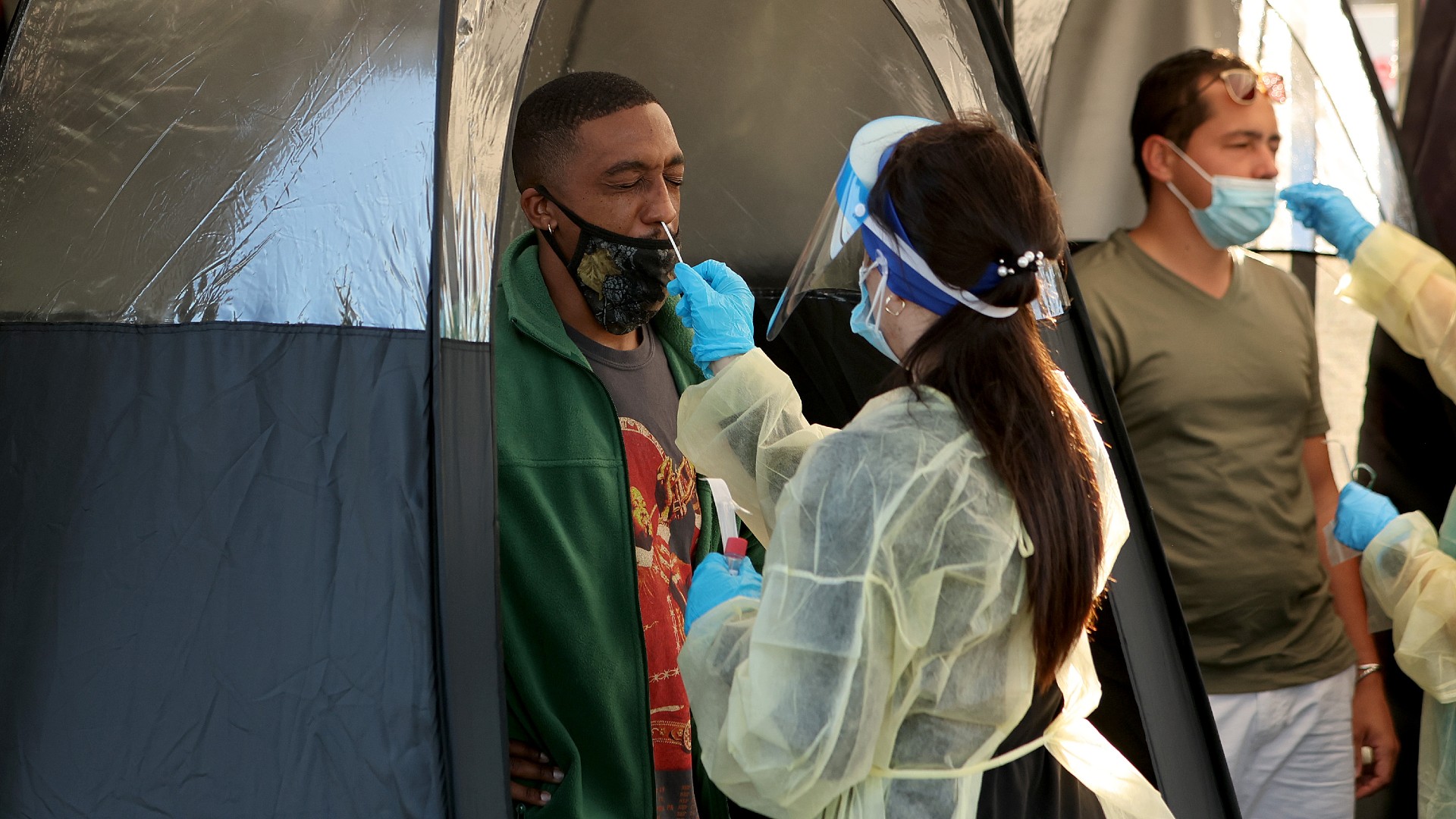

Such a metric is helpful, in part, because some COVID-related deaths may have been overlooked due to a lack of testing and underdiagnosis of the disease during the pandemic's early days. The excess death rate also captures deaths that were not caused by COVID-19 itself, but rather the rippling effects the pandemic had on society.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: Genetic quirk could explain why not everyone shows symptoms of COVID-19

For example, homicides in the U.S. surged by more than 30% from 2019 to 2020, while deaths involving alcohol spiked 25.5% over the same time period, likely due to a rise in stress and anxiety. While the healthcare system buckled and people avoided hospitals during each COVID-19 wave, many people did not receive adequate care for existing conditions, which is partially what led to an uptick in deaths related to health issues like heart disease, for instance.

Due to these combined factors, excess death rates in the early pandemic were harrowing, consistently exceeding 20% in 2020 and 2021. From March 2020 to March 2022, the country's excess deaths totaled more than 1.1 million, which is 15% higher than the official COVID-19 death toll reported over that same time period, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

But in 2023, the U.S. turned a corner.

Starting in January, excess death rates began to plummet, falling from about 17% at the end of December to 2% by January's end. Since then, the rates haven't exceeded 3% and have often lingered around zero.

Some estimates suggest that COVID-19 deaths are still being undercounted. However, based on national data from the CDC and the Human Mortality Database, which is compiled by the University of California, Berkeley, and the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research in Germany, the recent fall in excess death rates likely reflects a return to pre-pandemic levels of mortality.

One sobering reason why these excess death rates have dipped is because COVID-19 has already claimed the lives of many of the people most vulnerable to the disease, particularly those aged 65 and older, which accounted for more than 75% of total coronavirus deaths in the U.S. leading up to October 2022, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Related: COVID-19 is no longer a global health emergency, WHO says

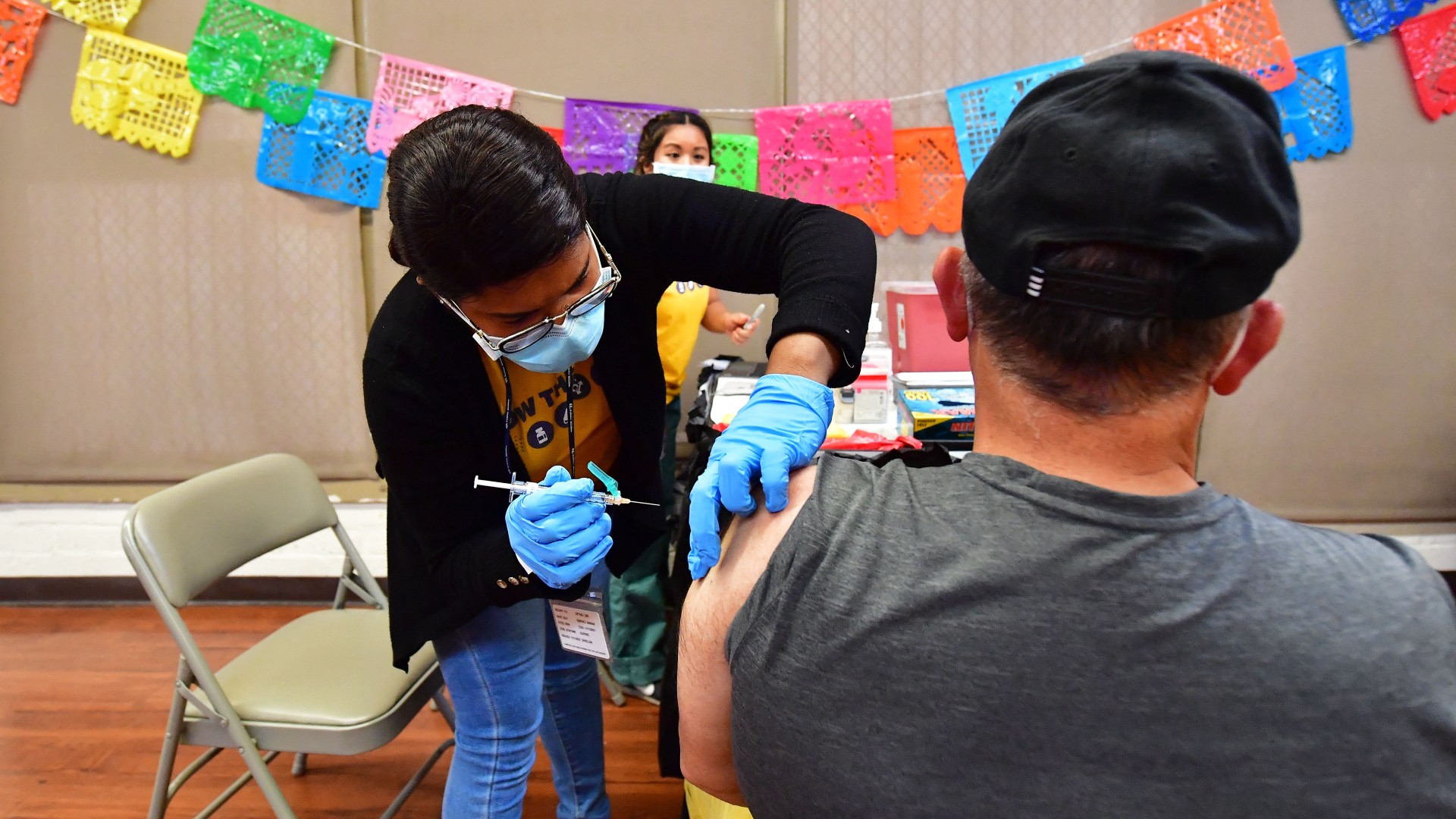

However, one of the main explanations for the excess death rate bottoming out is that the vast majority of the U.S. has now gained some immunity to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. By 2022, more than 95% of U.S. residents had COVID-19 antibodies coursing through their veins, whether from being infected, receiving a vaccine or both, which means we've likely "realized a community immunity" across the country, Doron said.

And while individuals with immunity can still contract COVID-19, they are much less likely to die from it, according to a study published in March in the journal The Lancet. Additionally, effective treatments for COVID-19, including the antiviral Paxlovid, became more widely accessible last year and help reduce the disease's severity, The New York Times reported.

So, is the pandemic over?

The federal Public Health Emergency for COVID-19 was ended in May, meaning the government no longer considers the disease a national emergency but still regards it a public health priority. The excess death rate data reflects that transition out of a state of emergency, according to Dr. Paul Monach, the chief of rheumatology at the VA Boston Healthcare System.

"I think that we're in a state where, in putting all these data together and not seeing much excess death overall, that it's reasonable to say yes, the pandemic is over," he told Live Science. "But I think it's still important to figure out who is still at risk."

For the majority of immunocompromised people, vaccines are effective at preventing severe COVID-19 infections, Doron said. But some groups remain vulnerable, including those age 65 and older and people who have received organ transplants, who must take immune-suppressing drugs.

And although more than 80% of people in America have received at least one dose of the vaccine, there are still a lingering few who have refrained. And getting just one dose of the original vaccine does not protect as well against now-circulating coronavirus variants, which could lead to more severe infections, according to the CDC.

"There remain pockets and enclaves of individuals, particularly in rural America, that are unvaccinated or under-vaccinated and who either have limited access to treatments or are unaware of options who are still vulnerable," Andrew Stokes, an assistant professor at the Boston University School of Public Health, told Live Science.

While excess death rates are currently low, in July alone, about 30 to 70 people in the U.S. have died of COVID-19 each week, according to preliminary CDC data. And there is always the risk of a new, immunity-evading coronavirus variant emerging in the coming years and causing spikes in mortality, Monach told Live Science.

As the initial pandemic winds to a close, it will be important to remain vigilant to these changing circumstances.

Kiley Price is a former Live Science staff writer based in New York City. Her work has appeared in National Geographic, Slate, Mongabay and more. She holds a bachelor's degree from Wake Forest University, where she studied biology and journalism, and has a master's degree from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus