Elephants inhale water at 330 mph

Suction in elephants' trunks is more powerful than scientists thought.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Elephants' trunks suck a lot — and that's a good thing. Powerful suction allows elephants to deftly grasp small and delicate pieces of food, even fragile tortilla chips that would otherwise be crushed or fumbled by the grip of their muscular trunks.

High-speed video recently revealed that this suction success stems from the forcefulness of elephant inhalation. Researchers calculated that elephants can inhale at speeds of over 336 mph (540 km/h), which is more than 30 times the speed of expelled air during a human sneeze (about 10 mph or 16 km/h) and faster than a Japan Rail bullet train (199 mph or 320 km/h, according to Japan Rail).

Their trunks can also hold more than you might think. An elephant can expand its trunk's diameter by dilating its nostrils; this reduces the thickness of the trunk's inner walls and increases the space inside by about 64%, according to a new study.

Related: Photos: Finding elephant tracks in the desert

An elephant's trunk — despite weighing a whopping 220 pounds (100 kilograms) — is capable of performing unexpectedly dainty tasks: from painting "self-portraits" to grasping cereal flakes by pinching them in the trunk's tip, Live Science previously reported.

Prior research showed that elephants can blow air through their trunks to manipulate food that's just beyond their reach, and the authors of the new study wondered if elephants also used their trunks like personal vacuum cleaners to suck up tasty treats, as they do when they suck up water or dust to spray over themselves, according to lead study author Andrew Schulz, a doctoral candidate in mechanical engineering at Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta.

"A loud vacuuming sound"

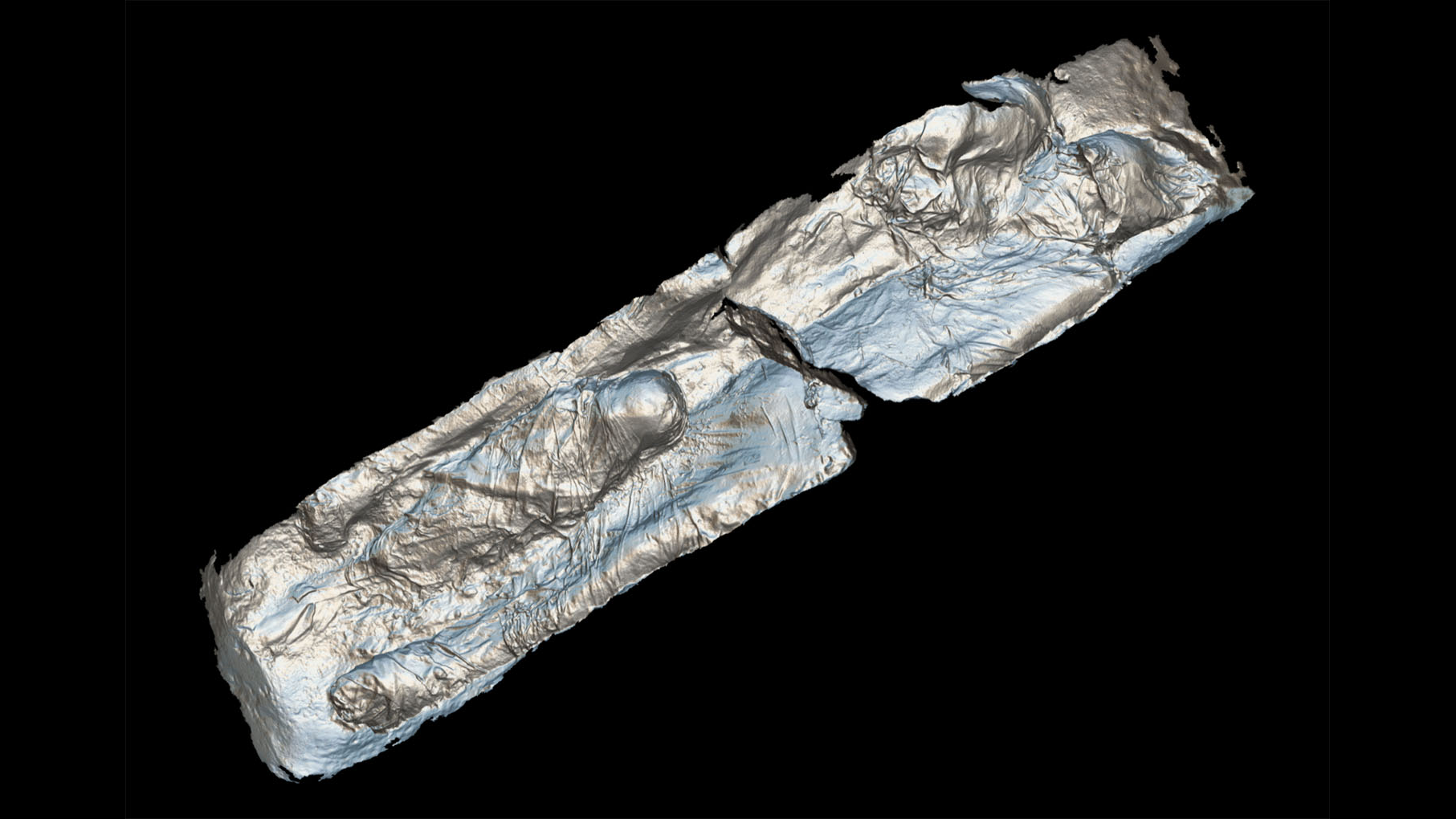

Using three video cameras, the scientists recorded experiments with a 34-year-old female African elephant at the Zoo Atlanta, presenting her with tortilla chips and cubed pieces of rutabaga. Next, they recorded video and collected ultrasound measurements of the elephant's trunk as it slurped water from an aquarium. The study authors then calculated trunk capacity and pressure using data from their observations and from trunk measurements of the Zoo Atlanta elephant, and of a frozen trunk borrowed from the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The elephant inhaled to lift multiple small objects as well as single items. When there were more than 10 small pieces of rutabaga on the table, the elephant used suction to pick them up, producing "a loud vacuuming sound," the study authors reported. For the more delicate chips, the elephant used suction in two ways: sucking up the chip from a distance, or pressing her trunk directly on the chip first, then applying suction to lift it from the table. These chip-lifting efforts were remarkably gentle, the scientists reported.

"Even after repeated attempts, the elephant could usually pick it up without breaking it," the researchers wrote.

Aquarium experiments further demonstrated the speed of the elephant's mighty inhalation, with pre-soaked chia seeds in the water helping to show the liquid's flow. The elephant hoovered up nearly a gallon (4 liters) of liquid in 1.5 seconds, which initially seemed like more liquid than a trunk could reasonably hold, Schulz said

"At first, it didn't make sense: An elephant's nasal passage is relatively small, and it was inhaling more water than it should," he said in a statement. "It wasn't until we saw the ultrasonographic images and watched the nostrils expand that we realized how they did it. Air makes the walls open, and the animal can store far more water than we originally estimated."

Elephants can suction feed because their specialized respiratory system accommodates unusually high lung pressure, which generates air velocity that is unmatched among land animals, the study authors wrote. For instance, human lungs can generate barely enough suction to elevate "a small piece of paper," and a person trying to lift a tortilla chip by inhaling would have to position their nose no more than 0.02 inches (0.4 millimeters) from the target, according to the study.

Even then, a human probably couldn't suck hard enough to do the job, as "any fluid leaks between the chip and nose would make lifting infeasible," the scientists wrote.

The findings were published online June 2 in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus