Is Atlantic hurricane season getting worse (and is climate change to blame)?

Rising sea levels and increasing sea surface temperatures can produce more intense hurricanes.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

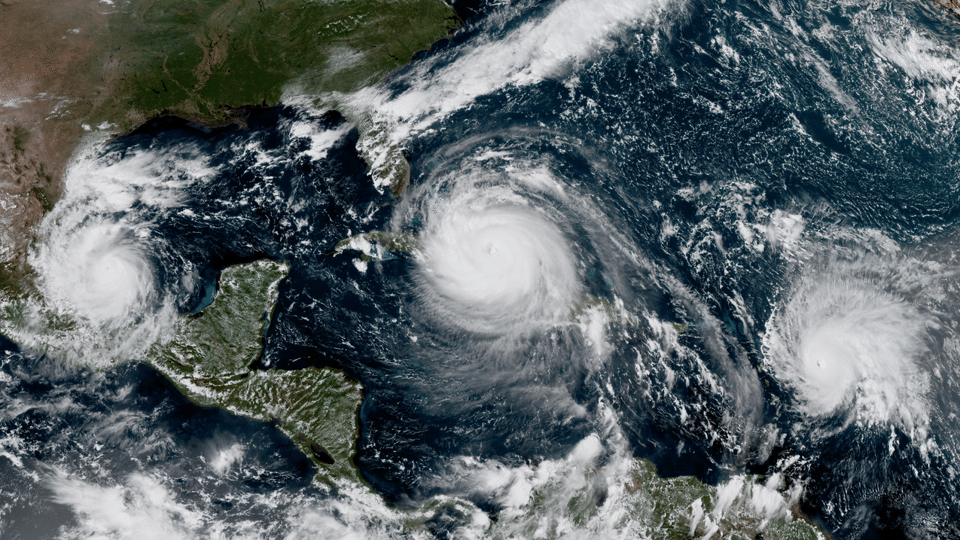

With Cuba and Florida left reeling after Hurricane Ian, which made landfall in September 2022 and was one of the region's most powerful and destructive storms in decades, it is tempting to attribute the carnage of yet another deadly hurricane season to climate change. But is climate change the culprit? Recent studies have linked climate change to environmental conditions that fuel hurricane season, but the connection between global warming and individual hurricanes is far from settled science.

While there is overwhelming evidence that human activities have directly caused sea levels to rise and the planet to get warmer — both of which are factors that make hurricanes deadlier — it remains unclear if climate change is fueling a significant increase in the number of hurricanes or intensifying tropical storms that make landfall.

"Hurricane activity is occurring on the backdrop of higher sea levels, which increases coastal flooding risk — that much is clear," said Thomas Knutson, who studies climate change and hurricanes at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (GFDL).

"The overall risk — how the frequency and intensity of storms is affected by global warming — is much more complicated," Knutson told Live Science.

Related: Hurricane season 2022: How long it lasts and what to expect

A warming planet will, as a rule, give us more intense hurricane seasons, researchers have discovered. Rising sea levels, driven by climate change, mean more coastal flooding from storm surges when hurricanes make landfall. And global warming also affects precipitation, with an estimated 7% increase in rainfall for every 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) of increased sea surface temperature, scientists reported April 12 in the journal Nature Communications. As human activities cause sea levels and surface temperatures to rise, hurricanes are packing more of a punch, in the form of flooding and heavy rainfall, Live Science previously reported.

Along these lines, some climate models have predicted that a 2-degree-Celsius (3.6 F) increase in global temperatures would result in a greater percentage of hurricanes reaching Category 5 (sustained wind speeds of 157 mph, or 252 km/h), would increase hurricane wind speeds by about 5% on average, and would lead to more storms making landfall in the U.S., researchers reported in 2013 in the Journal of Climate. In an earlier study, published in 2005 in the journal Nature, scientists found such a strong correlation between Atlantic hurricanes and sea surface temperatures that they warned we could see a 300% increase in hurricane activity by 2100.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But in spite of these dire predictions, we have not yet seen a significant increase in global hurricane activity. One confounding factor is that, while warmer sea surfaces are ideal breeding grounds for hurricanes, storms that collide with a warm atmosphere tend to fizzle out before causing much damage, researchers reported in a Nature study published June 27. This may explain why, even as human activities have caused the planet to warm by 1 C since the late 1800s, we haven't seen an upward trend in the number or intensity of hurricanes over the past century — and why the Nature study found that climate change may be linked to a global decrease in the number of hurricanes.

"Increased greenhouse gases may cause sea surface warming, which increases hurricane intensity," Knutson said. "But there's even more warming in the upper troposphere, and that puts the brakes on hurricane intensity." Knutson nonetheless expects to ultimately see an uptick. "We think global warming will still result in a net increase in hurricane intensity, but not nearly as much as if we had only sea surface warming," he said.

Although we haven't necessarily seen more hurricanes globally over the past century, there has been an increase in hurricane frequency and intensity in the Atlantic basin over the past 40 years. But even that increase may not necessarily be due to climate change. Other factors, such as the reduced manufacture and use of aerosol products, which harm Earth's ozone layer, had a surprising impact on global temperatures that may have temporarily affected hurricane formation, according to a 2022 study published in Science Advances. While greenhouse gases cause global warming, aerosols block sunlight and cool the planet. When the U.S. began cutting back on aerosols, this dramatic reduction may have caused a temporary temperature bump that increased the frequency and intensity of Atlantic hurricanes, the researchers reported.

However, it's possible that factors other than aerosols alone were responsible for this change.

"There has been a big uptick in hurricanes in the Atlantic basin since 1980, but we don't know whether that's a greenhouse gas-driven signal, because of changes in aerosol use or just natural variability," Knutson said.

Given the number of variables that can affect hurricane formation and strength, it is therefore "premature to conclude with high confidence that human-caused increasing greenhouse gasses have had a detectable impact on past Atlantic basin hurricane activity," according to an Oct. 3 report authored by Knutson for NOAA's Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory. The report cites lingering concerns that increases in storm activity in the Atlantic Ocean since 1980 may be attributable to a combination of factors, including decreases in the manufacture and use of aerosol products, global volcanic activity, and even natural variability.

Nevertheless, Knutson added, climate change will almost certainly make future hurricane seasons more dangerous, with more frequent coastal flooding, increased rainfall, and warming seas favoring the formation of more intense storms.

Indeed, the shift is already well underway. In 2020, researchers analyzed data from 4,000 tropical cyclones spanning 39 years, from 1979 to 2017, and concluded that hurricanes are getting stronger and major tropical cyclones are becoming more frequent — just as models predicted, Live Science reported.

"On average, we expect hurricanes to get more intense and have higher rates of rainfall due to climate change," Knutson said. As for Hurricane Ian, which caused hundreds of deaths and was Florida's deadliest hurricane since 1935, according to the The Washington Post, "instead of saying that Ian is a result of climate change, we'd rather say that storms like Ian are likely more intense than they would have been had they occurred in preindustrial times," Knutson said.

Joshua A. Krisch is a freelance science writer. He is particularly interested in biology and biomedical sciences, but he has covered technology, environmental issues, space, mathematics, and health policy, and he is interested in anything that could plausibly be defined as science. Joshua studied biology at Yeshiva University, and later completed graduate work in health sciences at Cornell University and science journalism at New York University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus