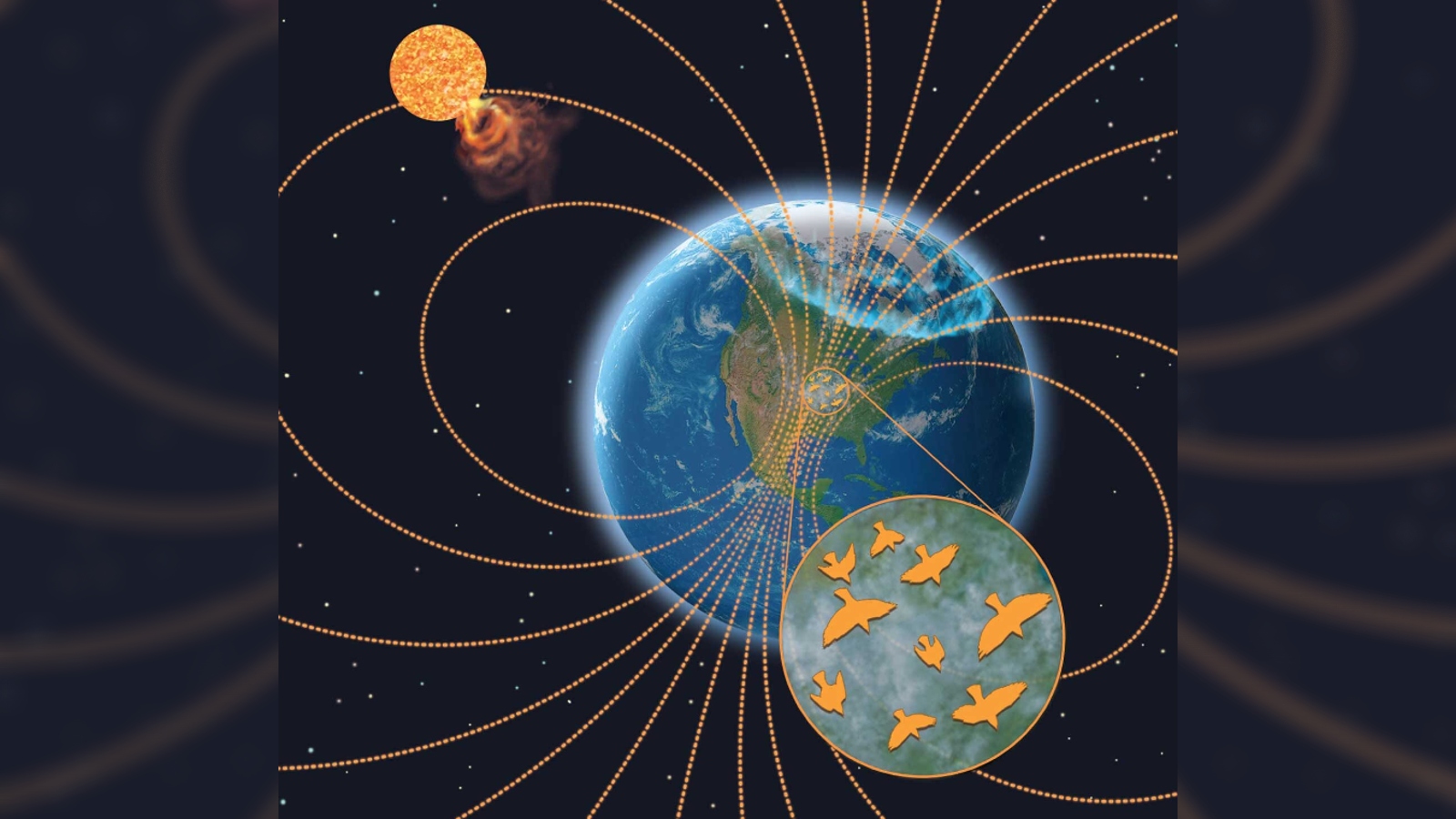

Upcoming solar maximum could scramble migrating birds' internal compass, new study shows

By analyzing how birds migrated across the U.S. over a 23-year period, researchers have shown that solar weather events can seriously disrupt the navigation of the wandering avians.

Migratory birds in the U.S. struggle to properly navigate when solar storms and other types of space weather disrupt their ability to sense Earth's magnetic field, a new study shows. The findings suggest that these birds may be seriously handicapped over the next few years as the sun ramps up toward its explosive peak — the solar maximum.

The sun regularly spits out bursts of high-energy particles and radiation, such as coronal mass ejections (CMEs), or strong gusts of solar wind. When those outbursts slam into Earth, they can cause temporary fluctuations in the planet's magnetic shield, or magnetosphere. Scientists already knew these geomagnetic disturbances interfere with other animals' magnetoreception, or ability to sense the magnetosphere.

In the study, which was published Oct. 9 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers studied the migratory patterns of a wide range of nocturnal migratory birds over a 23-year period. This included perching birds, like thrushes and warblers; shorebirds, such as sandpipers and plovers; and waterfowl such as ducks and geese.

The team analyzed more than 3 million radar images to track how the birds moved across the central flyway of the U.S. Great Plains — a major migratory corridor that spans more than 1,000 miles (1,610 kilometers) between Texas and North Dakota. Using magnetic field data collected by instruments on the ground during the same period, the researchers were able to see if the avians' behavior changed during geomagnetic disturbances.

Related: 10 signs the sun is gearing up for its explosive peak — the solar maximum

After analyzing the data, the team discovered that during geomagnetic disturbances, there was a 9% to 17% decrease in the number of birds attempting to migrate. The birds that did migrate during disturbances had more trouble correctly navigating their normal routes, researchers wrote in a statement.

"Our results suggest that fewer birds migrate during strong geomagnetic disturbances and that migrating birds may experience more difficulty navigating," study lead author Eric Gulson-Castillo, a doctoral candidate at the University of Michigan, said in the statement. This was most apparent during autumn, he added.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers also found that when the birds' navigation was compromised, they were more likely to let the wind guide them instead of magnetic field lines. In these situations, the birds decreased their "flight effort," or the amount of energy they put into fighting against the wind, by around 25%. These findings suggest that during these disturbances the birds "may spend less effort actively navigating in flight," Gulsen-Castillo said.

A large majority of the birds from the study seemed unaffected by space weather. However, for a small minority, failed migrations seriously reduced their chances of survival due to missing out on better weather conditions, easily available food and potential breeding opportunities.

Related: 10 of the biggest birds on Earth

During solar maximum, geomagnetic disturbances become more common as the sun spits out more CMEs and solar wind becomes stronger. The 23-year study period likely included at least three solar maximums, so the effects of this period have already been taken into account. However, the upcoming solar maximum, which is likely to begin within the next year, is expected to be much more active than previous cycles, which could increase the risk to migrating birds.

Experts are already worried that the magnetoreception of large migratory whales, such as gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus) and sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus), could be severely impacted during the upcoming solar maximum, which is likely to cause many to get lost or even accidentally beach themselves. Other animals that sense the Earth's magnetic field to navigate, such as turtles and fish, could also be affected.

The researchers hope that by learning more about this invisible threat we can be better prepared to help species that are at risk.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus