Ancient bird with T. rex-like skull discovered in China

A 120 million-year-old bird fossil from China has some rather unusual dinosaur-like features in its otherwise standard avian skeleton, including a weirdly T. rex-like skull.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

About 120 million years ago, a fearsome bird with a skull that looked eerily similar to that of a Tyrannosaurus rex flew the early Cretaceous skies, hunting for a meaty meal to gobble down, a new study finds. A newly described specimen of this previously unknown species provides clues about how birds began to finalize their evolutionary divergence from the rest of the dinosaurs.

Modern birds are descended from dinosaurs, making them the only dinosaur lineage that survived the planet-shaking asteroid impact that wiped out the rest of their kind around 66 million years ago. But exactly how birds evolved from the rest of the theropods — a bipedal group with hollow bones and three toes or claws on each foot, which includes avian dinosaurs as well non-avian dinosaurs, such as raptors like Velociraptor — is still unclear.

Researchers unearthed the new species, which they named Cratonavis zhui, at a fossil site in China. The fossil's age suggets C. zhui likely appeared somewhere between the earliest known bird, Archaeopteryx, which lived about 150 million years ago during the Jurassic period, and the Ornithothoraces, a dinosaur-era group which had already evolved many traits of modern birds.

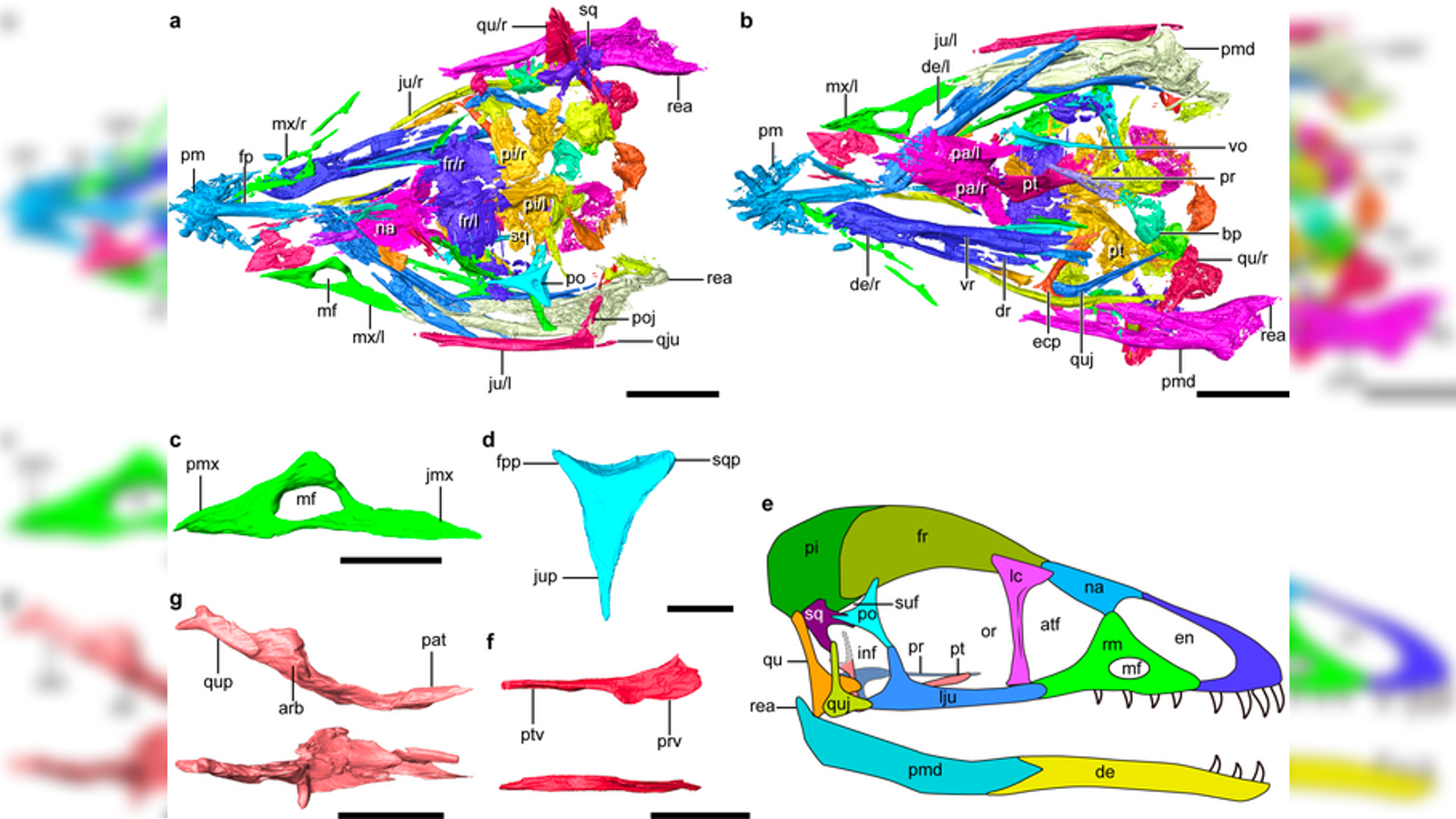

In a new study, published Jan. 2 in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution, researchers analyzed the new fossil to see what traits it shared with both groups. After studying the fossils with a high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scan, which allowed them to virtually reassemble the bones in 3D, the team found that, despite a majority of the skeleton being very similar to Ornithothoraces, certain bones shared a surprisingly strong likeness to non-avian dinosaurs. The most striking similarity was in the skull, which has a shape that is "nearly identical to that of dinosaurs such as T. rex," researchers wrote in a statement.

Related: How did birds survive the dinosaur-killing asteroid?

The specimen's raptor-like skull is notable because it would have prevented C. zhui from moving its upper bill in relation to its lower jaw. Modern birds are capable of moving both parts independently, which is believed to have greatly contributed to their enormous ecological diversity today, study lead author Zhiheng Li, a paleontogolost at the Chinese Academy of Science's Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP), said in the statement. It is therefore surprising to know that this trait developed so late in birds' evolutionary history, he added.

C. zhui also has an unusually elongated scapula, a shoulder bone used during flight, and first metatarsal, a bone found in the foot, compared with modern birds.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The scapula plays an important role in flight because it helps rotate birds' shoulders and beat their wings. The elongated scapula in C. zhui likely "compensated for the overall underdeveloped flight apparatus in this early bird," study co-author Min Wang, a paleoornathologist at IVPP, said in the statement.

However, the extended metatarsals are likely leftover from land-dwelling raptors who required longer versions of the bone to help them run. Over time, these bones evolved to be much shorter in birds to allow them to use their hallux, or big clawed toe, to land on branches and grab prey from the air instead of running, study co-author Thomas Stidham, a paleoornathologist at IVPP, said in the statement.

The unexpected lengths of both the scapula and first metatarsal "highlight the breadth of skeletal plasticity in early birds," study co-author Zhonghe Zhou, a paleoornathologist at IVPP, said in the statement. This plasticity suggests that certain skeletal traits could have evolved independently from one another across the birds' evolutionary tree, a phenomenon known as convergent evolution, but more fossils are needed to tell for sure.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus