Oddly modern skull raises new questions about the early evolution of birds

A fossil skull from a toothy early relative of today's birds shows a weirdly modern skull configuration, raising new questions about the early evolution of birds.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The earliest birds on Earth may have been more modern-looking than scientists expected — a discovery that raises new questions about a murky period in evolutionary history.

The first birds diverged from two-legged theropod dinosaurs around 165 million to 150 million years ago, during the Jurassic period, according to a 2015 paper in the journal Current Biology. They coexisted with dinosaurs during the Cretaceous. After the mass extinction that wiped out the nonavian dinosaurs about 66 million years ago, birds took off, evolutionarily speaking (they were already adept at flight).

But a more detailed understanding of this process is elusive, in part because there are barely any bird fossils from the Cretaceous. This was a crucial period of bird history, because the dino-killing asteroid also wiped out many ancient lineages of birds, leaving only the survivors to give rise to modern birds. That leaves a lot of questions about what the first birds looked like before this great winnowing.

"This event was really pivotal in terms of bird evolutionary history, because it dictated which lineages of bird-like animals were winners and losers," Daniel Field, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Cambridge in the U.K., told Live Science.

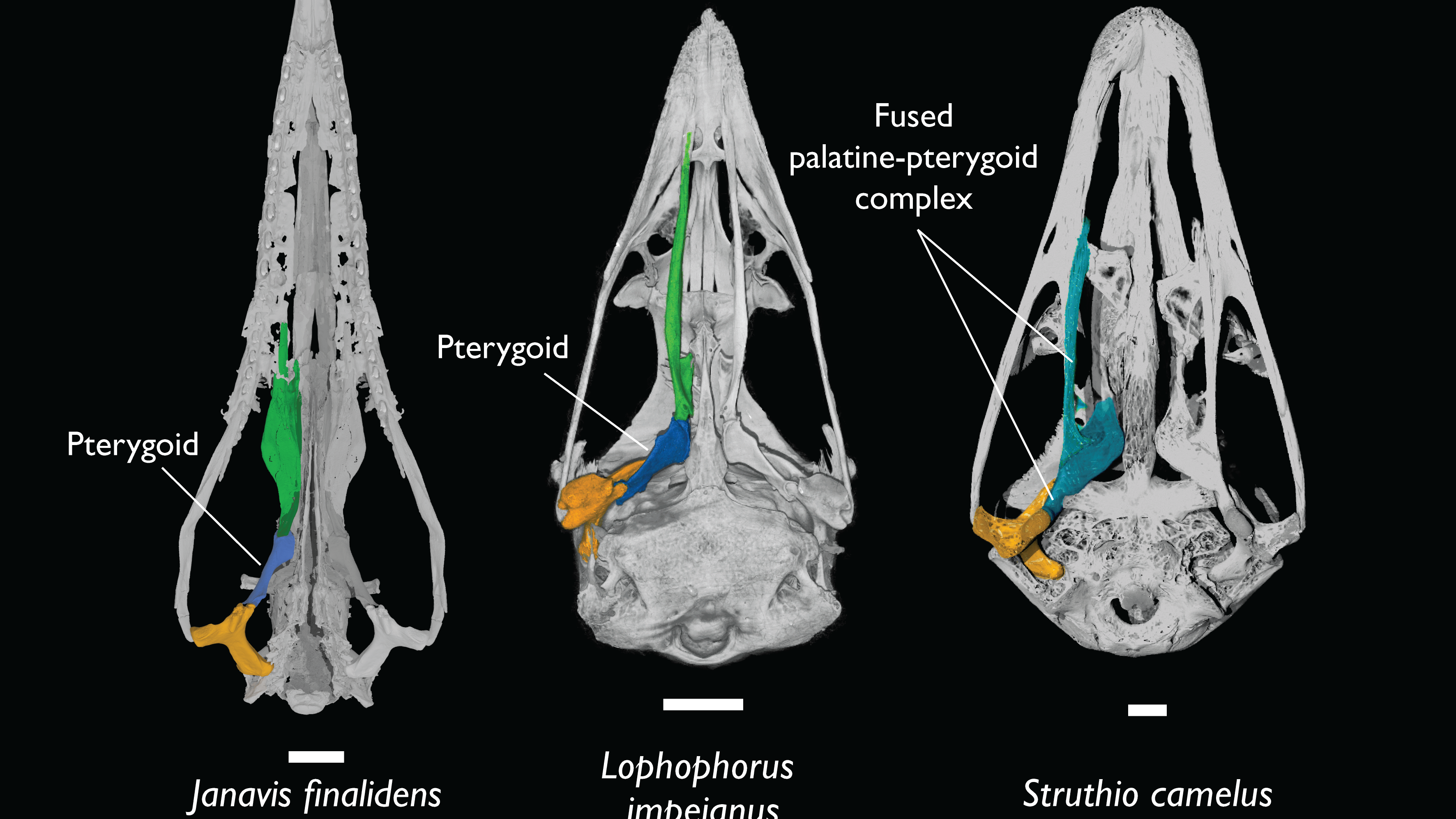

Enter a new discovery by Field and his colleagues: Janavis finalidens, a vulture-size, toothed bird that isn't directly related to any modern birds but was a close relative of modern bird ancestors in the final days of the dinosaurs. This newly described species surprised Field and his team because of a quirk of its skull: The bird's palate (what would be the roof of the mouth in humans) is unfused, giving the animal a mobile upper beak, like that of a modern duck. This was surprising, because scientists had thought the most primitive birds had fused palates and rigid upper beaks, much like today's emus and ostriches.

Related: How did birds survive the dinosaur-killing asteroid?

The new finding, published Nov. 30 in the journal Nature, suggests an alternative hypothesis: that the earliest birds looked "modern" and the "primitive" beak of emus and ostriches may have evolved later.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It's an interesting new piece of information that definitely complicates the picture," said Jingmai O'Connor, associate curator of fossil reptiles at Chicago's Field Museum. "But what it says, we really can't yet say," said O'Connor, who studies the dinosaur-bird transition but was not involved in the new research.

A single bone

To understand why the bird that Field refers to as Janavis is weird, you have to know a little about bird-science history. Back in the mid-1800s, British biologist Thomas Huxley (famous for being "Darwin's bulldog" due to his advocacy of evolutionary theory), working with what he had, split all birds into two ancestral groups: the "ancient jaws," or paleognaths, which had rigid, ostrich-like palates; and the "modern jaws," or neognaths, which had mobile, duck-like palates.

A mobile palate gives rise to a mobile beak, so scientists assumed that the unfused "modern jawed" birds were an evolutionary advance over their more primitive "ancient jawed" ancestors. With a mobile beak, birds are better at grooming, feeding, nest building and other tasks requiring dexterity.

Unfortunately, that neat story of evolutionary improvement doesn't seem to hold up. In the 1990s, paleontologists discovered a softball-size hunk of rock containing fossilized Cretaceous bird bones in a quarry in Belgium. For decades, no one could make much sense of the specimen. But using computed tomography (CT) scanning to look inside the fossil nondestructively, Field and his team eventually realized that the fossil contained something exciting: skull bones. In particular, a bone that had been previously identified as a bird shoulder bone was actually part of the palate.

That single bone revealed that Janavis, which lived 66.7 million years ago, had a "modern" palate.

"What this finding suggests is that the early ancestors of both modern neognaths ["modern jaws"] as well as modern paleognaths ["ancient jaws"] probably had a mobile palate," Field said.

Mixed-up lineages

It's possible, then, that all birds started out with what scientists have been calling "modern jaws," with some lineages only later picking up the "primitive" configuration.

But that isn't the only possibility, O'Connor told Live Science. Right now, researchers consider "modern jawed" and "ancient jawed" birds to be part of the same overarching group. But there is a "heretical idea," she said, that perhaps the "ancient jawed" birds evolved separately from a different long-tailed ancestor than the "modern jawed" birds. In that case, the last shared common ancestor of the two groups might be much further back in time than scientists thought.

In light of the new findings, it may be worth re-examining some of the first post-asteroid bird fossils to get a better grip on their skull anatomy, O'Connor said. More fossil evidence from the Cretaceous would be helpful, too, she said.

Field and his team plan to go deeper into the study of Janavis.

"We're going to continue taking a very close look at the anatomy of Janavis in order to shed a little bit more light on what its biology was truly like," Field said. "Answering that type of question may help us understand in better detail why these premodern bird lineages went completely extinct with the asteroid strike."

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus