Arctic sinkholes open in a flash after permafrost melt

Some permafrost zones thaw faster than expected and are reshaping the Arctic landscape.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Arctic permafrost can thaw so quickly that it triggers landslides, drowns forests and opens gaping sinkholes. This rapid melt, described in a new study, can dramatically reshape the Arctic landscape in just a few months.

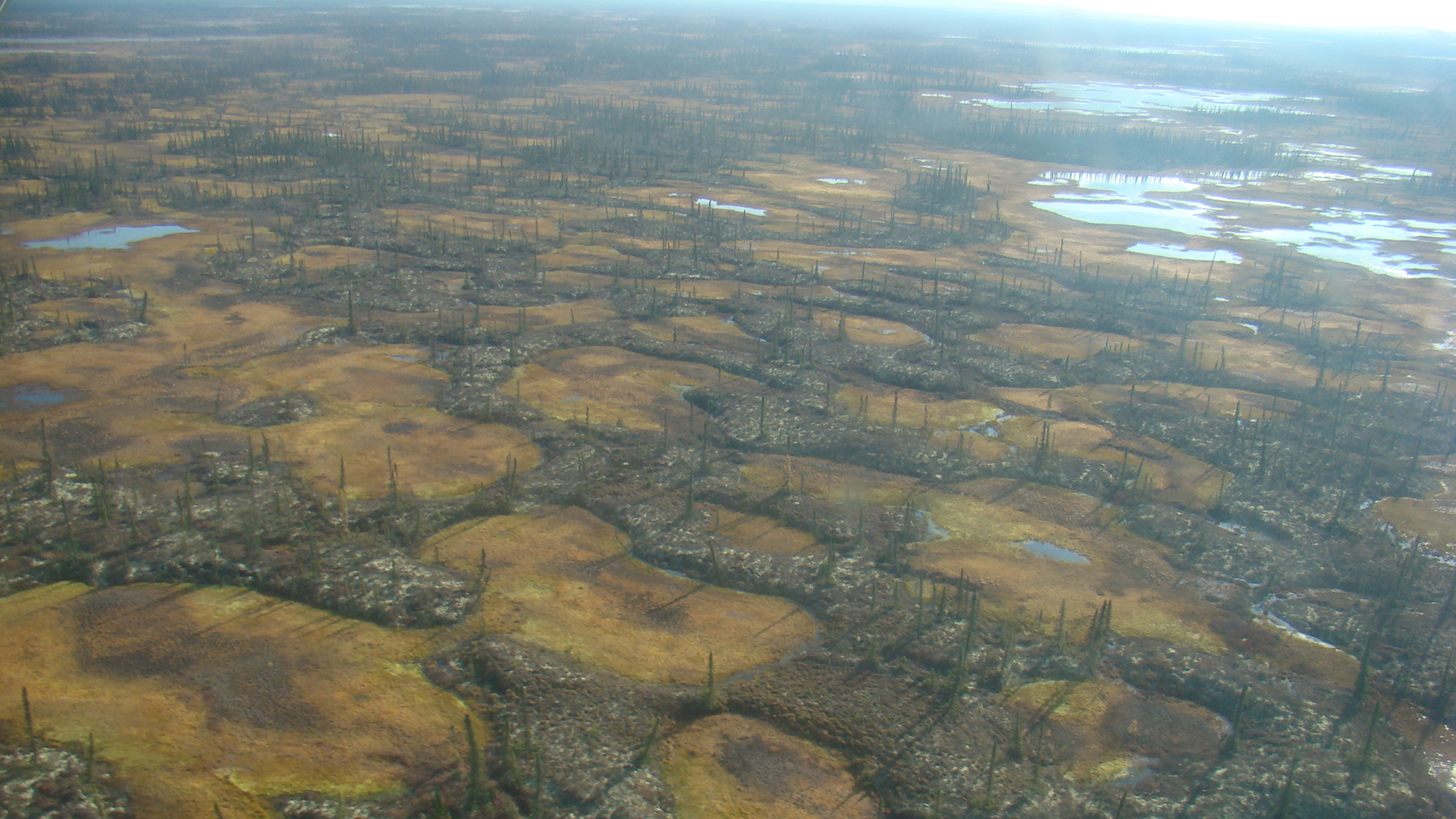

Fast-melting permafrost is also more widespread than once thought. About 20% of the Arctic's permafrost — a blend of frozen sand, soil and rocks — also has a high volume of ground ice, making it vulnerable to rapid thawing. When the ice that binds the rocky material melts away, it leaves behind a marshy, eroded land surface known as thermokarst.

Previous climate models overlooked this kind of surface in estimating Arctic permafrost loss, researchers reported. That oversight likely skewed predictions of how much sequestered carbon could be released by melting permafrost, and new estimates suggest that permafrost could pump twice as much carbon into the atmosphere as scientists formerly estimated, the study found.

Related: Photos: Perfectly preserved baby horse unearthed in permafrost

Frozen water takes up more space than liquid water, so when ice-rich permafrost thaws rapidly — "due to climate change or wildfire or other disturbance" — it transforms a formerly frozen Arctic ecosystem into a flooded, "soupy mess," prone to floods and soil collapse, said lead study author Merritt Turetsky, director of the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research (INSTAAR) at the University of Colorado Boulder.

"This can happen very quickly, causing relatively dry and solid ecosystems (such as forests) to turn into lakes in the matter of months to years," and the effects can extend into the soil to a depth of several meters, Turetsky told Live Science in an email.

By comparison, "gradual thaw slowly affects soil by centimeters over decades," Turetsky said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Creating feedback

Across the Arctic, long-frozen permafrost is melting as climate change drives global temperatures higher. Permafrost represents about 15% of Earth's soil, but it holds about 60% of the planet's soil-stored carbon: approximately 1.5 trillion tons (1.4 trillion metric tons) of carbon, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center.

When permafrost thaws, it releases stored carbon into the atmosphere. This release can then speed up global warming; this cycle is known as climate feedback, the scientists wrote in the study.

In fact, carbon emissions from about 965,000 square miles (2.5 million square kilometers) of quick-thawed thermokarst could provide climate feedback similar to emissions produced by nearly 7 million square miles (18 million square km) of permafrost that thawed gradually, the researchers reported.

And yet, rapid thawing from permafrost is "not represented in any existing global model," study co-author David Lawrence, a senior scientist with the National Center for Atmospheric Research, said in a statement.

Abrupt permafrost thaw was likely excluded from prior emissions models because it represents such a small percentage of the Arctic's land surface, Turetsky explained.

"Our study proves that models need to account for both types of permafrost thaw — both slow and steady change as well as abrupt thermokarst — if the goal is to quantify climate feedbacks in the Arctic," Turetsky added.

The findings were published online Feb. 3 in the journal Nature Geoscience.

- The reality of climate change: 10 myths busted

- In photos: The vanishing ice of Baffin Island

- Images of melt: Earth's vanishing ice

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus