Massive Snow Cannons Could Save West Antarctica's Ice Sheet

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Antarctica's western ice sheet is in danger of collapsing, but scientists may have an unusual solution: blasting trillions of tons of artificial snow across glaciers with snow cannons.

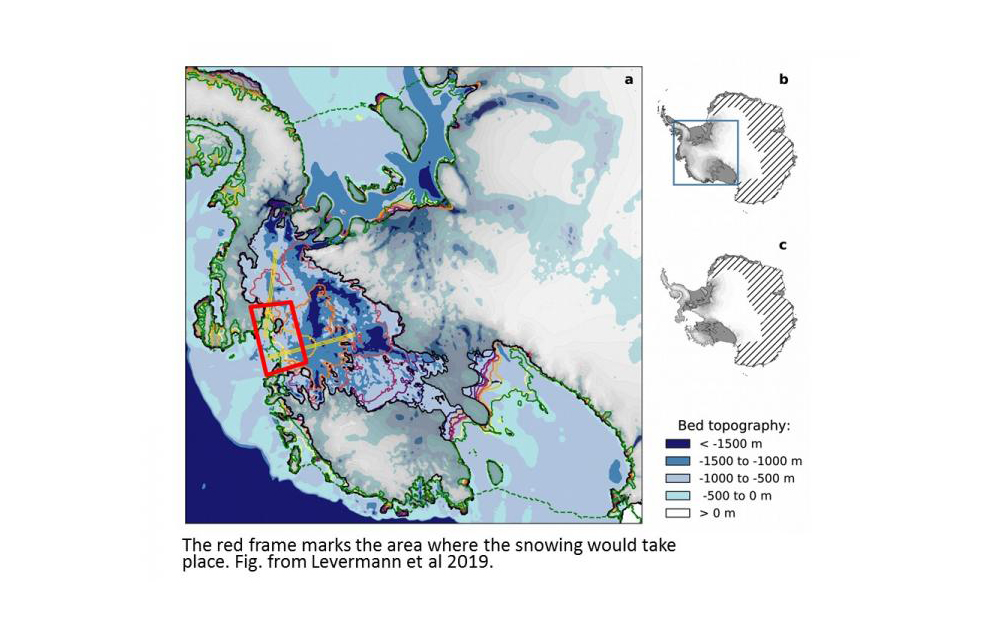

Spraying this artificial blizzard into the coastal area around Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers could stabilize the failing West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS), reducing ice loss that could drive potentially catastrophic sea level rise, new research finds.

But as intriguing as that extreme solution may sound, there would be considerable drawbacks; the effort would be prohibitively expensive and could harm sensitive ocean ecosystems, the researchers reported. [Antarctica: The Ice-Covered Bottom of the World (Photos)]

Western Antarctica is particularly vulnerable to climate change; decades of climbing temperatures have thinned the ice to the point where an estimated 24% of ice sheets in the western part of the continent are in danger of collapse. What's more, the melt rate is speeding up, with meltwater now flowing into the sea five times faster than it did in 1992, when surveys first began, Live Science previously reported.

"Ice loss is accelerating and might not stop until the West Antarctic ice sheet is practically gone," said study co-author Anders Levermann, a physicist at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) in Potsdam, Germany, and an adjunct senior research scientist at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University in New York City.

Without intervention to stop ice loss in Antarctica, sea level rise could reach nearly 10 feet (3 meters) — and coastal metropolises "from New York to Shanghai," will pay the price should the continent's western ice sheet collapse, Levermann said in a statement.

In the study, Levermann and his colleagues created computer simulations to evaluate how weak coastal ice might be strengthened. They found that artificial snow spread on the surface of the ice sheet where glaciers meet the sea would prevent ice sheet collapse; the technique would mimic natural precipitation in Antarctica while delivering substantially more snow than what is normally deposited there by seasonal storms.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"In practice, this could be realized by an enormous redisposition of water masses, pumped out of the ocean and snowed onto the ice sheet," Levermann said.

The researchers' simulations showed that stabilizing the ice sheet would require at least 8 trillion tons (7.25 trillion metric tons) of artificial snow, distributed with cannon-like snowblowers over 10 years. Siphoning ocean water to make the snow could further reduce global sea level rise by about 0.08 inches (2 millimeters) per year, the scientists reported.

But making snow in Antarctica would need a lot of mechanical infrastructure. Seawater would have to be transported to the ice sheet surface — a distance of about 2,100 feet (640 meters) on average — and then distributed across an area of over 20,000 square miles (52,000 square kilometers), according to the study. The researchers estimated that it would take 12,000 wind turbines to generate enough power just to move the water; desalination and snow-making would require even more energy.

And the wind farm would have to be constructed close to the coastline, which could destroy a pristine ocean environment, home to a unique diversity of marine life.

This would be "an unprecedented effort for humankind in one of the harshest environments of the planet," the scientists wrote. However, the enormity of the threat to humanity from Antarctica's unchecked ice loss — and the subsequent sea level rise — demands drastic and unconventional solutions such as this one, Levermann said in the statement.

Nevertheless, the snow-making option should not be seen as an alternative to global reduction of greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuels, which are the primary drivers of climate change, the scientists wrote in the study.

"This gigantic endeavour only makes sense if the Paris Climate Agreement is kept and carbon emissions are reduced fast and unequivocally," Johannes Feldmann, lead study author and PIK researcher, said in the statement.

The findings were published online July 17 in the journal Science Advances.

- Icy Images: Antarctica Will Amaze You in Incredible Aerial Views

- Images of Melt: Earth's Vanishing Ice

- Photos: Diving Beneath Antarctica's Ross Ice Shelf

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus