Unknown Group of Ancient Humans Once Lived in Siberia, New Evidence Reveals

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A pair of children's teeth that were lost 31,000 years ago in Siberia led scientists to the discovery of a previously unknown population of ancient humans.

These people inhabited northeastern Siberia during the Ice Age and were genetically distinct from other groups in the region, researchers reported in a new study.

The scientists analyzed genetic data extracted from the teeth, along with DNA from ancient remains found at other sites in Siberia and central Russia. In doing so, they reconstructed 34 ancient genomes dating to between 31,000 and 600 years ago, piecing together the puzzle of how Paleolithic humans spread across Siberia, and then crossed over the Bering Land Bridge into the Americas. [Photos: Newfound Ancient Human Relative Discovered in Philippines]

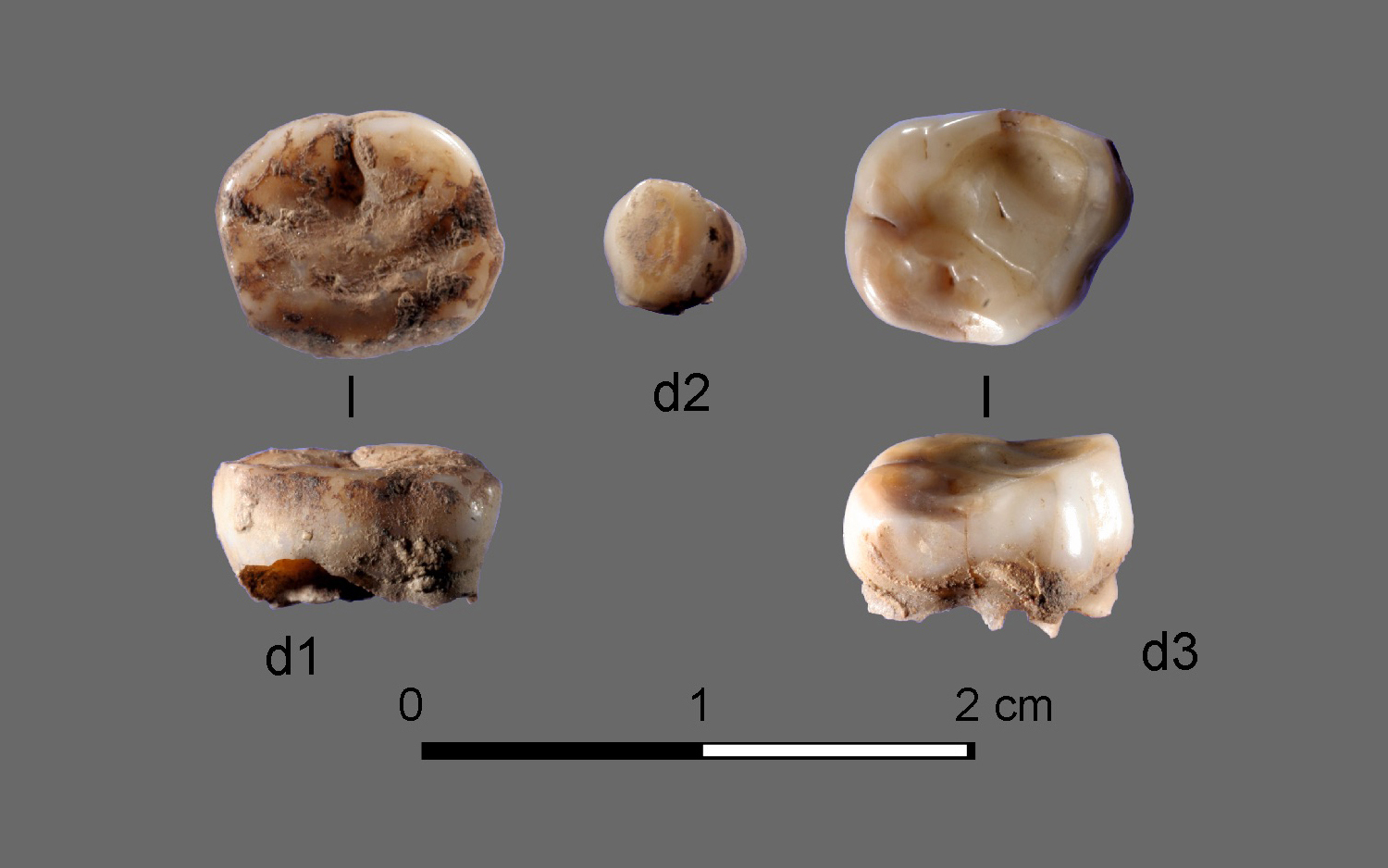

The tiny teeth belonged to two unrelated male children and were found at the Yana Rhinoceros Horn Site (RHS) on Siberia's Yana River, a locale that was first discovered in 2001. Though Yana RHS contained thousands of artifacts — among them stone tools, ivory objects and animal bones — these teeth are the site's only known human remains.

Together, the teeth and the artifacts are the earliest evidence of human occupation in the region; the teeth also represent the oldest Pleistocene human remains found at such high latitudes, the scientists reported.

Surprisingly, even though the Yana River site is in the northeastern part of Siberia, DNA from the teeth showed scientists that these "Ancient North Siberians" were distantly related to ancient hunter-gatherers from western Eurasia, and likely arrived in Siberia shortly after Asians diverged from Europeans.

By comparison, other Siberian populations that arrived later in the region — including those from whom contemporary Siberians are descended — trace their beginnings to eastern Asia, according to the study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Networks of hunter-gatherers

Humans are thought to have inhabited the high Arctic as early as 45,000 years ago, based on evidence such as cut marks on butchered mammoth bones. The authors of the new study estimated that the people in Yana diversified from other Eurasian people about 40,000 years ago, said lead study author Martin Sikora, an associate professor of GeoGenetics at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark.

Differences between ancient Siberian populations are tracked not only genetically, but also through variations in preserved material culture, which are "consistent with the changes we observe in genetic ancestry over time," Sikora told Live Science in an email.

Ancient DNA can also reveal intriguing glimpses of how the Ancient North Siberians may have lived, as patterns of genetic diversity can offer clues about population size and social organization, Sikora explained. The researchers' findings suggested that the people at Yana may have lived in a group of as many as 500 individuals and that there were no signs of inbreeding in the children's genomes.

"This is despite the very remote location, suggesting they were organized in larger networks with other hunter-gatherer groups," Sikora said.

Three migration waves

Based on the genetic data, the researchers determined that humans populated Siberia in at least three major migratory waves. The now-extinct Ancient North Siberians arrived first, from the west; they were followed by two migratory waves from eastern Asia. The third of those waves was a group known as Neo-Siberians, to which many contemporary Siberians can trace their ancestry.

Around 18,000 to 20,000 years ago, descendants of the Ancient North Siberians intermingled with people from the two eastern Asian groups. A partial skull found at a site near Siberia's Kolyma River dates to about 10,000 years ago and shows genetic similarity to Ancient North Siberians and to the eastern Asian group that became ancestors to Native Americans, according to the study.

This indicates that the previously unknown Siberian group participated in the interbreeding that eventually resulted in humans who migrated to North America, said study co-author Eske Willerslev, an evolutionary geneticist and director of The Lundbeck Foundation Centre for GeoGenetics at the University of Copenhagen.

"This individual is the missing link of Native American ancestry," Willerslev said in a statement.

According to the authors, while the Ancient North Siberians were not the direct ancestors of Native Americans or contemporary Siberians, "traces of their genetic legacy can be observed in ancient and modern genomes across America and northern Eurasia," revealing that the human history of populating ancient Siberia — and the New World — is a far more complex tale than the present genetic record would suggest, the researchers wrote.

The findings were published online June 5 in the journal Nature.

- Photos: Is Ice Age Cat Mummy a Lion or a Lynx?

- 25 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries

- Top 10 Mysteries of the First Humans

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus