2018's Science Superlatives: The Biggest, Oldest, Smelliest and Cutest

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Science Superlatives

This past year has been a busy one for science: Researchers confirmed general relativity, cloned primates for the first time and found that ancient humans and Neanderthals were constantly getting frisky.

The year also saw some findings that were just a little bit extra. As 2018 draws to a close, we look back at some of the record-breaking discoveries of the year.

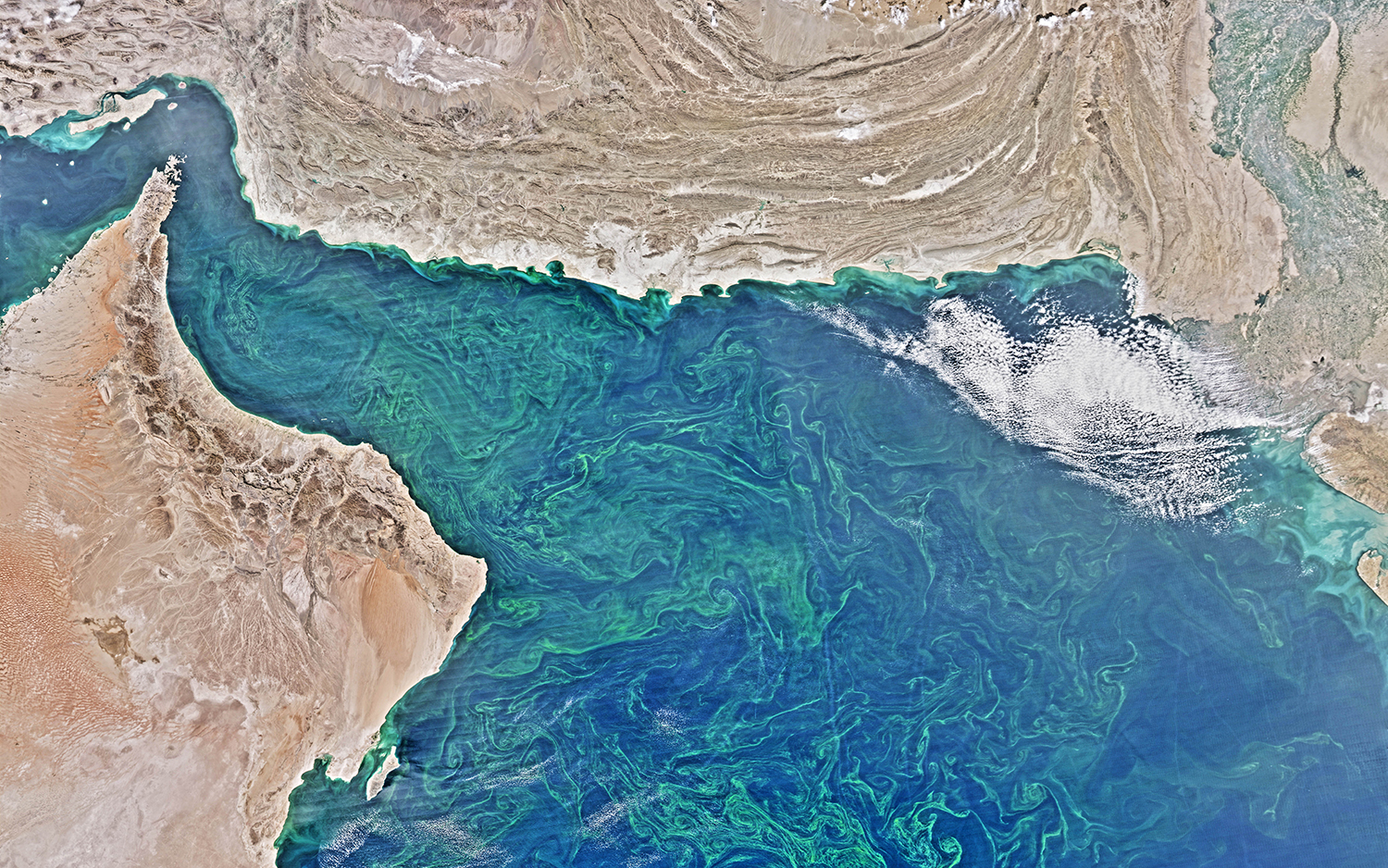

Largest 'dead zone'

Researchers have known since the 1990s that there is a large dead zone in the Arabian Sea, where massive algal growth siphons off all the oxygen in the water, leaving an area where few organisms can survive. But this year, scientists were sobered to find that this dead zone has expanded far more than expected.

"The ocean is suffocating," study lead author Bastien Queste, a marine biogeochemist and research fellow with the School of Environmental Sciences at the University of East Anglia in England, said in a statement in May.

The dead zone's boundaries change slightly with the seasons, but the oxygen-starved area is now about the size of Florida, the researchers reported. [Read more about the largest dead zone]

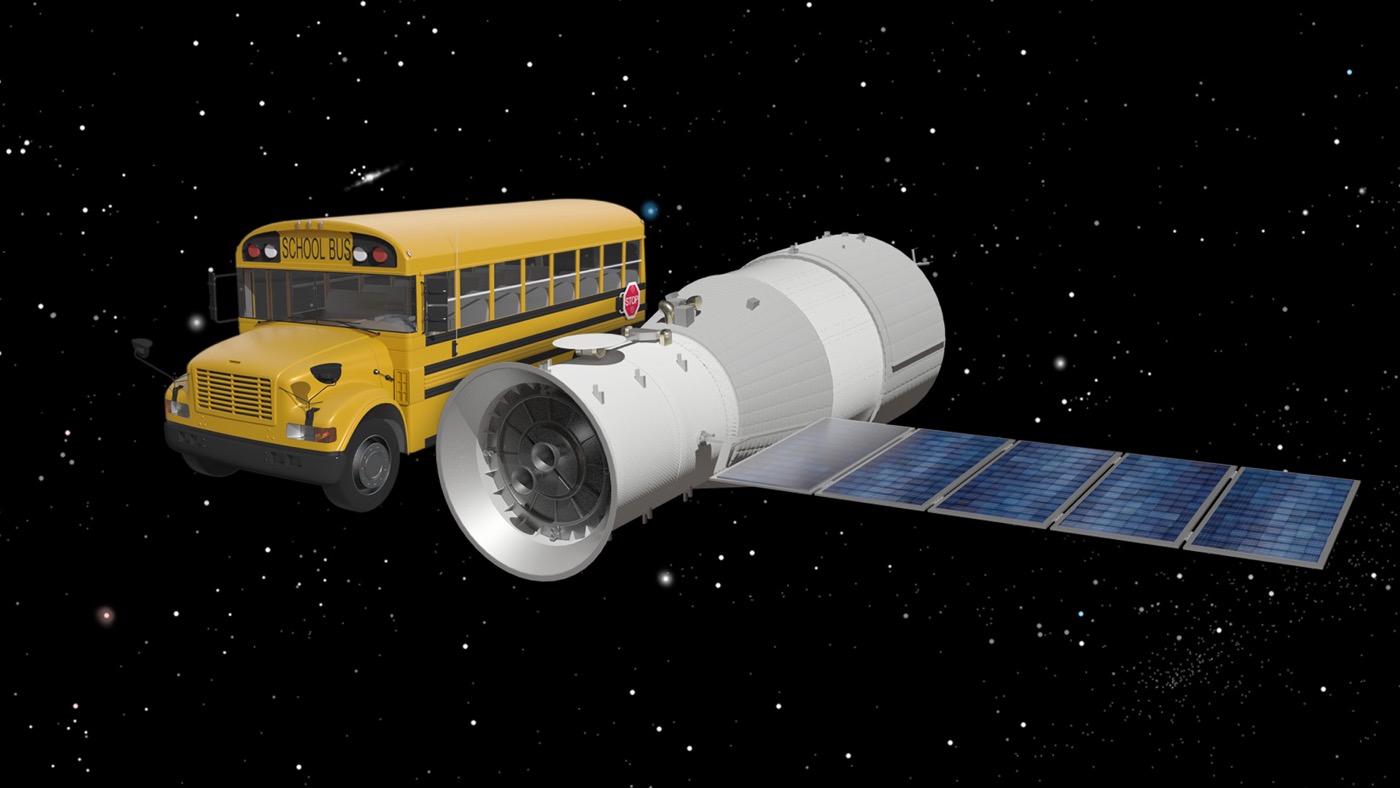

Almost-biggest man-made thing to fall from space

The crash of the Tiangong-1 space station this year was the biggest satellite to fall from the sky in 2018. Fortunately (and predictably), it made its landing on April 2 in a remote section of the Pacific. But while Tiangong-1 made for an exciting 2018 record-breaker, it was not the largest thing to ever fall from space, even in recent memory. That honor goes to Mir, the Russian space station that went into a controlled re-entry in 2001. At 132.3 tons (120 metric tons), Mir far outweighed the 9.4-ton (8.5 metric tons) Tiangong-1. [Read more about the Tiangong-1 fall from space]

Cutest discovery

Awww … a minuscule, translucent octopus discovered riding some ocean trash in the Pacific is a shoe-in for cutest scientific discovery of 2018.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The pea-size cephalopod was found by park researchers at Hawaii's Kaloko-Honokōhau National Historical Park in August. It was likely either a day octopus (Octopus cyanea) or a night octopus (Callistoctopus ornatus), park researchers told reporters. As adults, these octopuses can have arm spans ranging from 3 to 7 feet (0.9 to 2 meters), but as babies, they're pipsqueaks. [Read more about the totally adorable octopus]

World's largest bird

Birds may be the descendants of dinosaurs, but do they really have any business weighing 1,760 pounds (800 kilograms)? A thousand years ago, apparently so. A new species of elephant bird found fossilized in Madagascar weighed just that and stood 9.8 feet (3 meters) tall. That size puts it on a par with a small sauropod, the long-necked dinosaur Europasaurus. Appropriately, the flightless bird's discoverer named it Vorombe titan — Vorombe means "big bird" in Malagasy. [Read more about the world's largest-known bird]

The Southern Hemisphere's biggest wave

Speaking of things that are way too big… a wave the size of an 8-story building crashed off the coast of New Zealand's Campbell Island this May, breaking the record for the Southern Hemisphere's largest recorded wave by 6 feet (1.77 meters).

The monster wave was 78 feet (23.8 m) tall and hit during a storm in which the winds exceeded 74 mph (130 km/h). The largest recorded wave ever, though, is still one detected in the North Atlantic in February 2013. That one was a mind-boggling 62.3 feet (19 m) tall. [Read more about this monster wave]

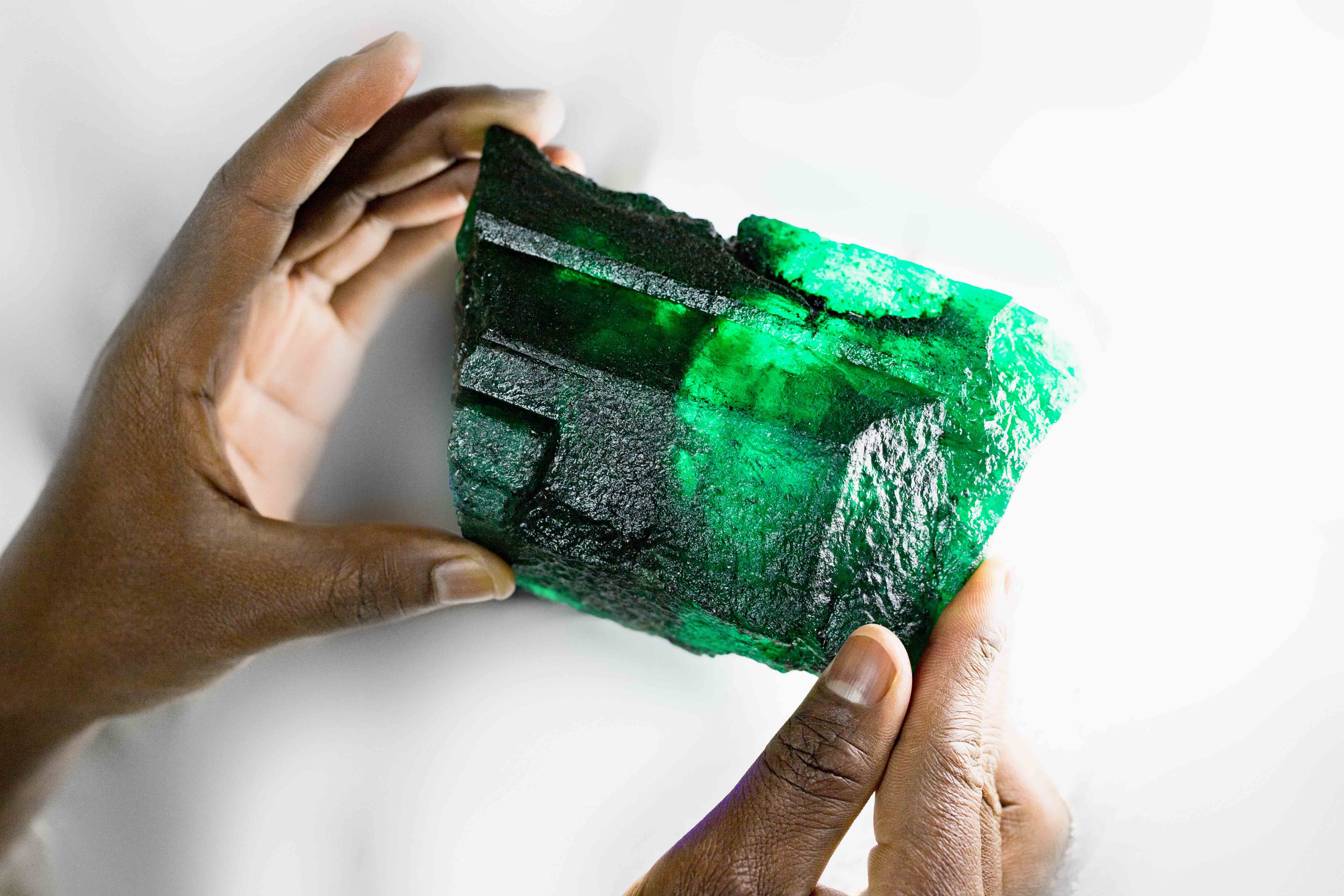

The most drool-worthy gemstone

A gorgeous green emerald unearthed in Zambia's Kagem mine is one of the biggest ever found — and certainly one of the most covetable scientific discoveries of the year.

The "lion emerald" clocked in at 5,655 carats and 2.5 pounds (1.1 kilograms). It got its name because the Kagem mining company pledged 10 percent of the sale of the emerald to two lion conservation organizations. According to news reports, an Indian jeweler purchased the gem at an auction in November for an undisclosed sum. [Read more about the hefty emerald]

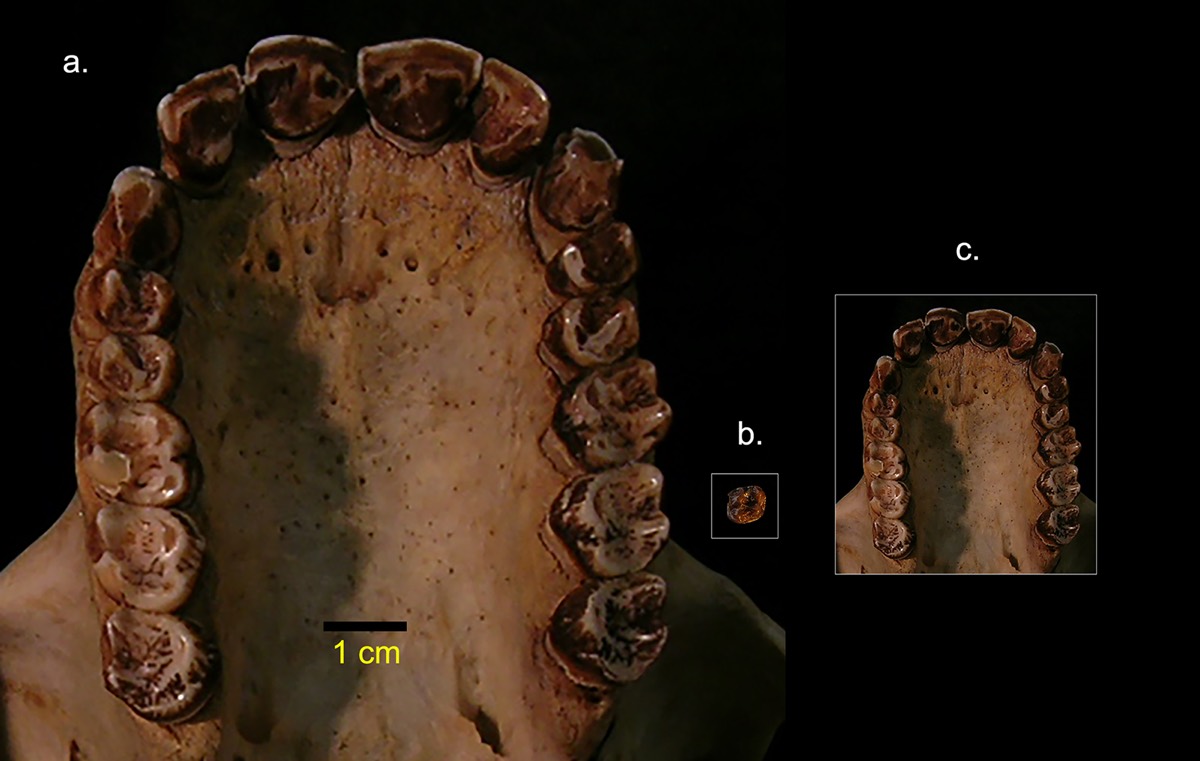

Earth's smallest ape

The world's smallest ape was the size of a newborn human baby and it lived 12.5 million years ago.

This little nugget of primate was discovered in the form of three tiny fossil teeth in Kenya in 2004, but researchers only announced the discovery this year after determining that the teeth were not matches for any known species of ancient or modern ape. Researchers suspect the mini-ape died out because it could not compete with the non-ape primates in its environment, small colobine monkeys. [Read more about this wee ape]

The smallest galactic cannibal

Galaxies sometimes scarf down stars from their neighbors. For a long time, astronomers suspected that only the biggest galaxies turned to this kind of cannibalism. But this year, researchers reported that they'd detected galactic cannibalism in a teeny-tiny galaxy.

The culprit was a galaxy with 100,000 times less solar mass than the Milky Way, known as the Sextans dwarf spheroidal. An analysis of the galaxy's star types suggests that it previously ate a nearby, even smaller, galaxy, researchers reported in October. [Read more about this little galactic cannibal]

A long-necked first

When Estefânia Temp Müller's brother found some fossils on some rural land in Agudo, Brazil, she knew just who to call: her paleontologist son Rodrigo Temp Müller, who surveyed the scene and organized an excavation. The dinosaur that he and his team uncovered turned out to be the oldest long-neck sauropod on record.

The species, dubbed Macrocollum itaquii, dates back to the Triassic between 227 million and 208.5 million years ago. It was a juvenile and would have been around 11 feet (3.5 m) long and weighed 220 pounds (100 kg). The dinosaur was probably a plant-eater, but may have eaten some meat as well, Müller told Live Science. [Read more about the record-breaking sauropod]

The biggest dying organism

The Pando quaking aspen is a whole forest of cloned trees in Utah sprouting from the same parent organism. At a whopping 13 million pounds (5.9 million kg) in weight and 106 acres (0.42 square km) in area, it's one of the largest colonial organisms on Earth.

It's also dying. Researchers this year found that very few new Pando sprouts are surviving, mostly due to consumption by mule deer. Humans, unfortunately, have to take the real blame. Human incursion killed the deer's natural predators, and their population in the area is too high. Conservationists have fenced off parts of Pando, which seems to be helping. [Read more about dying Pando]

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus